There was to be an unexpected and momentous sequel to the disaster at Aubers Ridge. For some months there had been growing dissatisfaction throughout the country with the conduct of the war, fuelled by lengthening casualty lists in the newspapers. There was an uneasy feeling that those in charge of the nation’s affairs had not been prosecuting the war with sufficient energy and determination. From the outset the Press had consistently supported the Government; news of the battles on the Western Front had been presented to an innocent and gullible public in the most favourable light; small gains were inflated into significant advances and setbacks were few. However, even the Press became a little restive after Neuve Chapelle when rumours began to circulate about a shortage of shells for the guns. Lord Northcliffe, proprietor of The Times and the Daily Mail, had been receiving detailed complaints for some time from both officers and men at the front about conditions in the trenches, including comments from a number of members of Parliament who had been commissioned soon after the outbreak of war. The censor had repeatedly refused to let him publish them. Public disquiet was now heightened by the return of the wounded from Neuve Chapelle and Second Ypres with stories of delays, bungled attacks and a demoralizing shortage of shells. Some hints of these criticisms at last began to find their way into the local and national papers.

For a little while it was possible for the Cabinet to maintain the line taken by Asquith and Newcastle. The disaster at Aubers Ridge on 9 May received little attention from the Press, and that little was hopelessly inaccurate and misleading. But within days echoes of the fiasco quickly began to reverberate down the corridors of Westminster and around the clubs in Pall Mall. With the arrival of the wounded and men on leave, stories started to circulate in London about another failed offensive by the First Army accompanied by heavy casualties. It was an explosive situation and it only needed a spark to set it off.

The spark was Colonel Repington. He was already aware that Sir John, incensed by the continuing failure of Kitchener and the War Office to respond to his demands for more ammunition, was considering going over their heads and appealing directly to leading politicians and the Press. As we have seen, he had watched the battle with the Commander-in-Chief, though it is difficult to reconcile this with his distorted piece published in The Times on 12 May.

French had left the Aubers Ridge battlefield early and returned, accompanied by Repington, to his headquarters. Here he found a telegram from the War Office instructing him to send 2000 rounds of 4.5-inch and 20,000 rounds of 18pdr ammunition from his scanty reserves to Marseilles for shipment to the Dardanelles. This was the last straw. If Sir John had harboured any doubts about the consequences of his proposed course of action, this order dispelled them. The combined effects of his next actions were to have far-reaching consequences for the Government, for Kitchener and in due course for himself. In his memoirs, entitled 1914, he describes what he did:

I immediately gave instructions that evidence should be furnished to Colonel Repington, military correspondent of The Times, who happened to be then at Headquarters, that the vital need of high-explosive shells had been a fatal bar to our Army’s success on that day [Repington could hardly have asked for more explosive copy!]. I directed that copies of all the correspondence which had taken place between myself and the Government on the question of the supply of ammunition be made at once, and I sent my Secretary, Brinsley FitzGerald, with Captain Frederick Guest, one of my ADCs, to England with instructions that these proofs should be laid before Mr Lloyd George (the Chancellor of the Exchequer), who had already shown me, by his special interest in this subject, that he grasped the deadly nature of our necessities. I instructed also that they should be laid before Mr Arthur J. Balfour and Mr Bonar Law [senior Conservative politicians who were also coopted members of Asquith’s War Council], whose sympathetic understanding of my difficulties, when they visited me in France, had led me to expect that they would take the action that this grave exigency demanded.

In political life it is rare for a single issue to bring about a great upheaval. Usually this is caused by several factors combining to create a situation where one further incident – a scandal, a resignation or a piece of ill-considered legislation – is sufficient to cause a violent reaction. Thus it was not the shell shortage a Aubers Ridge revealed by Repington that by itself brought down Asquith’s Government. His article simply served to focus the disappointment caused by the failure of the Aubers Ridge offensive, by the anger over the gas attack at Ypres which had caught our troops unprepared, the disquiet over the Dardanelles adventure, and by growing public concern at the leisurely and ineffective way the war was being conducted by the Liberal Government. All these matters now came together to create a volatile situation where one more blow might bring disaster down upon the Government. That critical blow, untimely and unexpected, was struck the very next day after Repington’s article.

It had not been easy for Asquith’s Cabinet to conceal the differences over the Dardanelles campaign between Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, and the First Sea Lord, Lord Fisher, his senior naval adviser. ‘Jackie’ Fisher, the creator of the modern navy, pugnacious, outspoken and ‘the darling of the Conservatives’ in Beaverbrook’s phrase, had made little secret of his opposition to the attempt to force the Dardanelles employing the Navy alone. He was even more hostile to later developments involving a military expedition and further demands upon the Royal Navy. Finally he could contain himself no longer and on Saturday, 15 May he resigned in protest against the Dardanelles ‘foolishness’.

This was the immediate cause of the downfall of the Liberal Government. In the next few days the political crisis came to a head. Fisher’s intemperate action led to a flurry of activity. It cast a shadow over the integrity and actions of the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, who at once saw Asquith and offered to resign. His offer was refused. At the same time, Fisher resisted all attempts by powerful friends, such as Churchill, Lloyd George and even the Prime Minister himself, to make him reconsider his decision and embarked on a bizarre course of behaviour that made his return to office out of the question. Bonar Law discussed the serious political situation with Lloyd George; they agreed it made a coalition government necessary and that Lloyd George should suggest this to Asquith. Such a proposal now suited Bonar Law and Balfour, while Lloyd George saw it as his chance to take a major, and more aggressive, part in the conduct of the war.

Meanwhile, Asquith was left in no doubt by the outcry from the Conservative party at this turn of events that to preserve national unity and present a harmonious parliamentary front he would have to form a coalition government and reconstruct his Cabinet. Balfour had made it clear that under no circumstances would the Conservatives stomach Churchill – who was anathema to his party – continuing in high office following Fisher’s departure. Asquith not unwillingly gave way and announced his intention to reconstruct his government to a tense House on 19 May. The Prime Minister moved swiftly to appoint leading Conservatives to his Cabinet, but it involved some painful decisions. In the reshuffle he removed Churchill from the Admiralty and made him Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, a post usually reserved, as Lloyd George commented, ‘either for beginners in the Cabinet or for distinguished politicians who had reached the first stages of unmistakable decrepitude’. He was also forced to sacrifice Lord Haldane, to whom the country owed so much. Many in the House expected Kitchener to follow him but Asquith realized that Kitchener’s continuing reputation and popularity among the public made this impossible. Others were not so deterred.

Lloyd George had naturally been intimately involved in the reconstruction process. All the time, however, he had been seething with anger at his realization that Kitchener had withheld Sir John French’s memos and letters about the shell shortage not only from the original Cabinet ‘Shells’ Committee of which Kitchener himself had been the reluctant chairman, but also from the Munitions of War Committee. Lloyd George saw his opportunity and he took it. On 19 May he wrote a lengthy letter to the Prime Minister stressing the points that had been made so forcefully to him by French in his report. He went on to complain about the way this information had been withheld from the Munitions Committee by the War Office (i.e. Kitchener) and stated that he would no longer preside over such a farce.

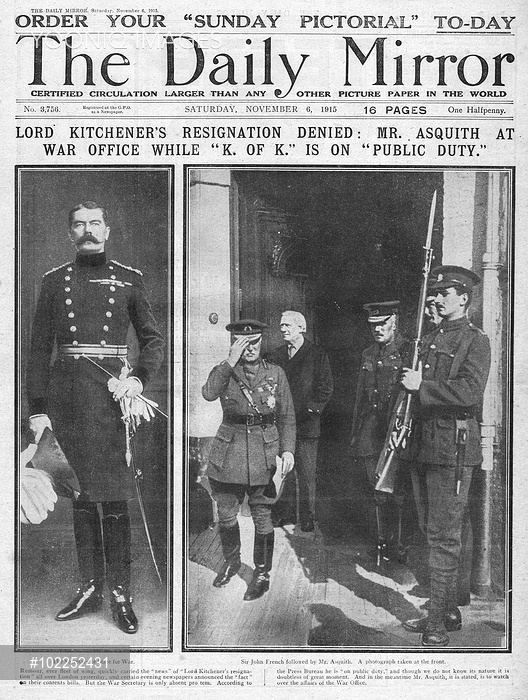

Two days later Lord Northcliffe re-entered the fray. He was no friend of Kitchener and he put the blame for the shell shortage firmly upon him. When he heard that Kitchener was to continue as Secretary of State for War in the reconstructed government he published a bitter personal attack upon him in the Daily Mail on 21 May under the headline: ‘The Shells Scandal: Lord Kitchener’s Tragic Blunder’. Many were upset by this attack upon a national institution, but there was scant sympathy for Kitchener among the Cabinet. He had upset too many people and made too many enemies; they had been intimidated too long by the stern, imposing figure of England’s most famous soldier and by the impact of his powerful personality.

Northcliffe followed up this attack on Kitchener by running a campaign for the next ten days on the theme of the shells ‘scandal’. If this had any effect at all, it was to strengthen Lloyd George’s hand in talks with the Prime Minister about the most effective way of settling the munitions problem. It was no surprise then that, when Asquith announced details of his new Cabinet to the House on 26 May, he also announced the most significant decision of all – his invitation to Lloyd George to form a Ministry of Munitions charged with the task of mobilizing the nation’s resources for armament production. The new Ministry would embody the functions of the former Munitions of War Committee, but with this crucial difference: it possessed the executive authority and the power that Lloyd George had been seeking for months. Lloyd George willingly gave up the Treasury, recruited ‘men of push and go’ and set off on the mission that was to contribute largely to the winning of the war and lead him to the premiership.

It is not within the compass of this book to deal with Lloyd George’s success in harnessing and expanding the engineering capacity of the nation. One might simply illustrate his achievements by comparing the brief bombardments and lengthy recriminations of the first half of 1915 with the intensity, weight and duration of the bombardment that opened the Battle of the Somme a year later.

If Lloyd George had been infuriated by Kitchener’s behaviour, Kitchener in his turn was very angry with French. He had endured for months a wrangle with his Commander-in-Chief over the supply of guns and shells to the Western Front. In the last few weeks he had had to contend with the Second Battle of Ypres and the offensive against Aubers Ridge, while at the same time being embroiled in Churchill’s scheme to force the Dardanelles and having to find men, guns and shells for it. He bitterly resented French going behind his back to stir up the Press and leading politicians against him. Sir John French had knowingly tempted the wrath of Achilles and in due course it was to descend upon him. His cause was not helped by the failure of Haig’s third attempt to make progress against Aubers Ridge; the Battle of Festubert had opened on 16 May and was now grinding to an expensive and inglorious halt. In September would come an even more disastrous offensive at Loos leading to calls for his resignation as Commander-in-Chief. Sir John’s reactions after the débâcle of 9 May proved a potent factor in his removal.

Kitchener was to soldier on in the Coalition Government until his tragic death the following summer, but his reputation had suffered a severe blow. The idol was seen to have feet of clay, and from this point his dominant role in the Cabinet and his influence over the conduct of the war began to wane.

‘Such an offensive, before an adequate supply of guns and high-explosive shell can be provided, would only result in heavy casualties and the capture of another turnip field.’

LORD KITCHENER, June, 1915 on a future offensive in France.