Aviation exploits in the Libyan campaign stimulated Italian aviation in 1912, when an air fleet fund raised three million lire for military aviation, indicating a burgeoning aviation consciousness there as elsewhere in Europe. That summer the army established an aviation inspectorate with airship and airplane battalions and an experimental institute. Turin’s Mirafiori field, where the airplane battalion located, became the center of Italian aviation. The Turin Polytechnical Institute founded an aeronautical laboratory in the winter of 1912–1913, and the first Italian aircraft factory, Società Italiana Transaerea (SIT), was founded there with French and Italian capital to build Blériots and then Farmans under license. SIT received contracts for the majority of the 150 planes ordered by the War Ministry in 1912 and 1913. In December Major Douhet, soon to be the commander of the airplane battalion, proposed an air arm of 25 squadrons of 94 planes and 150 pilots.

At a military competition for airplanes and engines held in April 1913, the judges, among them Douhet, declared no winners, finding that no domestic products equaled French machines, not a surprising conclusion given the primitive state of the Italian aviation industry. By default SIT remained the army’s essential supplier, since its 150 employees and potential monthly production of 10 to 14 planes monthly made it larger than the rest of the Italian aircraft industry. Despite the small size of the industry and its firms, Italian aviation’s pioneer age was beginning to fade in 1913, as artisanal airplane builders, no longer able to compete in sporting events and distance flights, which required substantial financial backing, dwindled.

Giulio Douhet, in his continued press advocacy of aviation, was urging Italian industry to support airplane development. If the campaign availed little, Douhet supported a close friend, the young aircraft designer Gianni Caproni, in his efforts to establish a factory. In June 1913, when Caproni was near financial ruin, Douhet persuaded Moris to make the factory part of the War Ministry’s administration, although Caproni resigned the post in 1914 because of inadequate government support for his experiments. By August 1914 Caproni had raised enough money to reopen his factory.

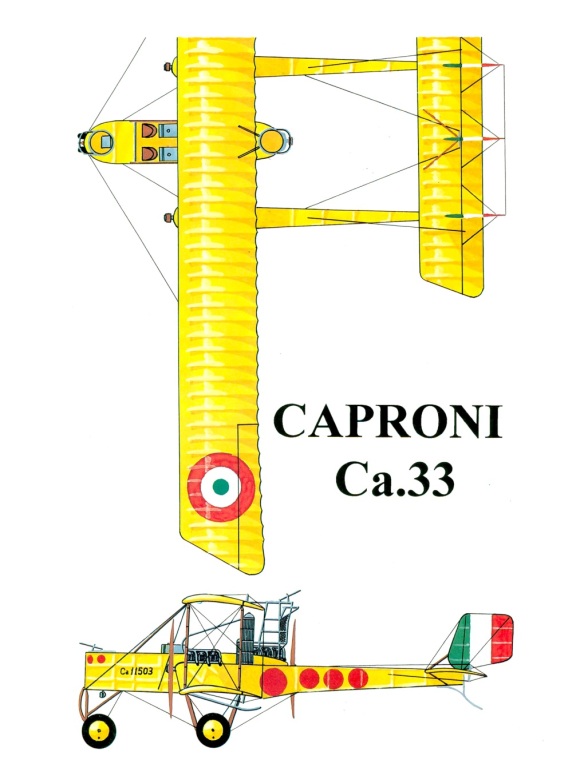

Caproni, who was convinced of the importance of a fleet of multi-engine bombers for tactical and strategic purposes. In 1913 he produced the first plane expressly conceived as a bomber, a trimotored craft powered by Gnome 80-hp rotaries, which Douhet had encouraged and perceived as a potential means of making aviation the decisive element of modern warfare.

By 1914 the Italian air arm comprised 11 squadrons of Blériots, Nieuports, and Farmans. The Italian aviation industry, like its counterparts in Russia and Austria-Hungary, was tiny and underdeveloped compared to the German and French industries. SIT lacked even a design office, while Caproni was concentrating on simplifying his bomber design for production. In 1914 the Italian War Ministry asked the engine industry for new projects to make Italy independent of foreign suppliers. Fortunately, Fiat, which had begun designing aviation engines in 1907 and had built dirigible engines since 1909, quickly developed the A10, a water-cooled 100-hp six-cylinder in-line patterned after German and Austrian types, and began its mass production in the fall. (Fiat had not previously encouraged aircraft engine orders because of the demands of automobile production.) Italian naval aviation was created only early in 1913 and remained insignificant in August 1914. Italy’s decision to remain neutral in the summer of 1914 meant that its air arm and industry would have until May 1915 before they faced the test of war.

Italy, with the Caproni Ca1, was the sole country to have a plane expressly designed as a bomber. Starting late in August, Ca1s powered by three Fiat 100-hp engines staged bombing raids on the Austro-Hungarian aviation camp at Aisovizza. Eight were at the front by the end of September. During the third and fourth Battles of the Isonzo from October to December, the Capronis bombed various targets and were ultimately placed at the Supreme Command’s disposal for long-range reconnaissance missions and bombing railroad junctions and stations.

The Supreme Command and the General Directorate of Aviation, preoccupied with enemy superiority and aviation’s inadequate organization in relation to the front’s demands, proposed programs to develop the industry despite problems in securing raw materials. Despite substantial plane losses, they planned to double the number of squadrons and to secure higher-hp engines. Italian aircraft production in 1915 totaled 382 planes and 606 engines. With the exception of 28 Capronis, the remaining craft were primarily French designs and a few German Aviatiks.

Italian aviation expanded in 1916, its first full year of war. At the end of the first trimester it comprised 30 squadrons, including 7 Caproni bomber squadrons. By the year’s end it had 44 squadrons, including 5 more Caproni squadrons.

Italian development of the bomber arm stands out in comparison with other air arms. In 1916 Italy had the most operational multiengine bombers of all the powers. Italy’s single, relatively limited, and stalemated front encouraged Guilio Douhet to seek dominance in the air, and the Capronis gave the air service the potential to do so. Enemy air attacks in January and February prompted the Italian supreme command to order an attack on Ljubljana on 18 February, in which Capronis dropped 1,800 kilograms of bombs. Symbolic of the Italian bomber force’s preeminence was that in this attack Italian aviators won their first gold medal, Italy’s highest award for valor. Two enemy planes killed the observer and wounded the pilot. Captain Balbo, the copilot, operated the machine gun until wounded in the arm and unable to fire. He then shielded the wounded pilot with his own body until he was hit and killed. Balbo’s sacrifice enabled the wounded pilot to return to the base with his crew’s bodies. The Capronis proved tenacious foes, but as losses mounted, they were forced to raid at night.

The June Italian counteroffensive in the Trentino-Alto Adige region included a raid by 34 Capronis on the Pergine Valsugana station. During the sixth Battle of the Isonzo, on 9 August 58 Capronis escorted by Nieuports bombed railway stations with 4,000 kilograms of bombs and repeated the raid on 15 August with 14 Capronis. On 13 September 22 Capronis bombed Trieste in response to Austrian raids on three Italian cities.

During 1916 the Caproni factory delivered 136 Ca 1s powered by three Fiat 100-hp in-line engines and 9 Ca 2s with a 150-hp Isotta-Fraschini replacing one of the Fiats. By the summer the Caproni factories near Milan were building more powerful versions using three 150- and 200-hp engines.

From January through April the Italian army air arm grew gradually. In May Gabriele D’Annunzio, at the invitation of General Cadorna, advocated repeated and massed bomber attacks on enemy artillery batteries and reinforcements and on Austro-Hungarian bases at Pola and Cattaro. In the tenth Battle of the Isonzo, on 23 May, 30 to 40 Capronis became the nucleus for repeated wave attacks in support of infantry attacks against enemy troops at the front and in the rear. Though the attacks’ imprecision limited their material results, an enemy officer’s war diary recounted that Italian planes flying so low that the bombs dropping from the fuselage were clearly visible spread fear and panic among Austro-Hungarian troops.

Italian dirigibles performed bombing raids in the spring and summer, but the Capronis held center stage. On the night of 2 to 3 August 36 Capronis took off at one-minute intervals to bomb Pola, with D’Annunzio aboard the first bomber. Twenty Capronis attacked the objective, and though intense antiaircraft fire struck 10 of them, they repeated the attack the next night, dropping a total of eight tons of bombs, and again on the night of 8 August.

On 19 August, the second day of the eleventh Battle of the Isonzo, 85 Capronis accompanied by more than 100 fighters and observation planes supported the infantry attack. For the 10-day period 19 to 28 August, an average of 225 planes raided enemy positions daily, for losses of 81 of the 300 Italian aircrew participating. The Italian bombing effort so impressed the American Bolling Commission that it concluded: “In Italy alone, of allied countries, do the conceptions of this subject appear at the present time to be on sufficiently broad and sound lines,” with “real and effective airplane bombing planned and in course of application.” A French observer, Commandant Le Bon, confirmed in September both the marked progress of Italian aviation in 12 months and the good results of bombing from Capronis, notwithstanding that conditions on the Southwest Front differed from those on the Western.

On 4 October 12 Capronis flew 400 kilometers over the sea to bomb Cattaro, but the end of the month witnessed the disastrous twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, the Italian collapse at Caporetto and retreat to the Piave, and the installation of a new director of aeronautical services.

The Caproni works at Taliedo was building one biplane and one triplane daily. Wing Commander Briggs found the Capronis, with their standardized wing ribs, bays, spars, and struts, designed with a view to ready production rather than ultimate aerodynamic efficiency and minimum weight, and he estimated that although the Handley Page bomber would be aerodynamically superior, a firm could build five Capronis to three Handley Pages.

Meanwhile, Giulio Douhet and Gianni Caproni were agitating for an Allied fleet of strategic bombers. Writing from prison in June, Douhet called for an Allied air fleet to bomb enemy cities in his essay “The Great Aerial Offensive” and urged Italy to build 1,000 planes, France 3,000, England 4,000, and the United States 12,000. In a July essay, “The Resistance of Peoples Facing the Long War,” he underlined the effect on morale of the German raid on London, the inadequacy of antiaircraft defenses, and the necessity of massive force. He further congratulated Caproni for the bomber raids on Austrian territory. Douhet was released from prison on 15 October, one week before the disaster at Caporetto, and he returned to aviation in 1918.

In an interview with Le Petit Parisien in October, Caproni advised that the war was one of materiel, which made it necessary to curtail enemy production. He lamented the excessive importance attached to aerial duels, the inadequate emphasis on raids on enemy bases, and suggested that the Allies needed a fleet of 200 to 300 bombers capable of carrying bomb loads of 2,000 kilograms.

Preparations for the climactic Battle of Vittorio Veneto occurred from August to mid-October, as the air arm attacked railroads and airfields, and the 21 October battle plan emphasized ground attack by all aircraft. From 22 October to 11 November the air arm had 407 to 478 planes, including over 200 of both fighter craft and reconnaissance planes and 38 to 56 bombers. General Bongiovanni used the SVAs for long-distance reconnaissance and light bombing, the Capronis to bomb airfields and the Vittorio Veneto munitions depots, and the fighters for air-combat and ground-attack missions. The battle ended on 4 November with complete victory and Austro-Hungarian capitulation. The army air service’s 504 frontline airplanes on 4 November represented nearly a tenfold increase from its 58 unarmed airplanes at the declaration of war in May 1915

In 1918 Italian bomber units gradually shifted from Caproni 450-hp to 600-hp bombers. Gianni Caproni shifted his construction from the biplane to a stronger and lighter, higher-hp triplane and then back to the biplane. The installation of Isotta-Fraschini engines—which were proving more reliable than Fiats—on Caproni triplanes improved their ability to perform missions over the Adriatic Sea, over which they sometimes flew as low as four meters altitude.

The Technical Directorate, working closely with industry, had successfully engineered the air arm’s expansion. Although Italy depended on France for its fighters throughout the war, the domestic industry supplied reconnaissance craft and bombers. The air arm needed more SVAs and Capronis and had only 58 Capronis in the final battle compared to 62 in August 1917. Caproni had difficulty securing sufficient Isotta-Fraschinis for production, although it managed to produce 40 CA3s 450-hp biplanes, 255 600-hp CA5 biplanes, and 35 CA4 triplanes. In 1918 the Italian aviation industry manufactured 14,840 engines and 6,488 planes, including 1,183 SVAs, 1,073 Pomilios, and 577 FBA flying boats.

Italian engine production had been particularly successful. All the engine firms—Fiat, Isotta-Fraschini, and Ansaldo—had followed identical programs of perfecting six-cylinder engines to obtain the maximum power for the minimum weight. Early in 1918 they were beginning to develop 12-cylinder V engines of 500 to 600 horsepower. Fiat, in addition to its 600-hp engine, was testing a promising 400-hp engine, the A15. In September Fiat was building 37 to 38 engines daily and moving toward 40 to 42, or 1,000 to 1,200 monthly.