330 B. C. E.-150 B. C. E.

After the Battle of Gaugamela, the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great conquered the remaining Persian provinces and began to capture the region of Afghanistan. Alexander ruled as King of Macedonia from 336 to 323 b. c. e., and during his short but impressive reign he achieved such feats as overthrowing the Persian Empire, carrying Macedonian arms to India, and laying the foundation to implement territorial kingdoms. Alexander would be regarded throughout history and time as a hero, a military genius, and a man of legend. During his reign, Alexander was widely admired and respected, and to have served alongside Alexander was enough to propel anyone to greatness and, in a metaphorical sense, to have walked among one of the gods.

In 356 b. c. e., Alexander was born in Macedonia to Philip II and Olympias, who was the daughter of King Neoptolemus of Epirus. From the age of 13 to 16, the philosopher Aristotle taught Alexander and inspired him with an interest in philosophy, medicine, and scientific investigation. A decisive moment in Alexander’s life came in 340 b. c. e., when his father Phillip II attacked Byzantium and left young Alexander in charge of Macedonia. These successful strategic battles for Alexander, including other instances such as his defeat of the Thracian people known as the Maedi, his command of the left wing at the Battle of Chaeronea, and his courage in breaking the Sacred Band of Thebes, would lay a solid foundation for his military career. However, his father’s divorce from his mother Olympias caused severe strain for Alexander, and after an argument at his father’s wedding feast to his new bride, Alexander and his mother angrily fled to Epirus. Phillip and Alexander would one day reunite, but the argument had threatened Alexander’s stance as the heir to Phillip’s kingdom.

Philip’s assassination in 336 b. c. e. was allegedly by the princes of the royal house of Lyncestis, a small kingdom in the valley of the Crna that had been included in Macedonia by King Philip. Alexander, who was much admired and highly praised by the army, succeeded the throne without disagreement. He immediately executed the conspirators of his father’s murder along with all possible rivals and those who were opposed to him. From the first moment of his accession to the throne, Alexander was intent on expanding the boundaries of the Macedonian Empire as begun by his father.

In 334 b. c. e. and after visiting Ilium (Troy), Alexander encountered his first enemy force, coming face to face with the Persian army at the Granicus River, located near the Sea of Marmara. The strategy of the Persian military was to attract Alexander across the river to annihilate the young king and his Macedonian troops. From a military history perspective, the style of fighting employed at the time was unique. In the combat formation, the front line of troops would be followed behind by another row of troops so that as the solider at the front of the line fell, another solider moved up from behind to replace those who fell in death or who were severely wounded and could no longer fight. Once the Persian and Macedonian armies began to clash, Alexander’s army continued to thrash the Persians and cut through the military procession. The Persian soldiers continued to fall until there were no more replacement troops and finally, the Persian line broke. Alexander’s army attained victory by pushing through the broken chain and driving the Persian forces into retreat. The majority of the Greek mercenaries under the rule of Darius III fell into carnage, but 2,000 survivors were sent back to Macedonia in slavery.

In the winter of 334-333 b. c. e., Alexander conquered western Asia Minor and exposed the region to the rule of the Macedonians. Shortly afterwards, Alexander overpowered the hill tribes of Lycia and Pisidia. While there is no question that Alexander was a great military leader, some of his victories were sometimes due to a stroke of luck. In one such instance, Alexander gained a significant advantage following the sudden death of Memnon, the skilled Greek commander of the Persian fleet. This severely hindered the Persian army, as Darius had advanced northward on the eastern side of Mount Amanus. While expertise and guidance on both sides were erroneous, Alexander found Darius drawn up along the Pinarus River. In the battle that followed, Alexander won a decisive victory as the struggle turned into a Persian riot and Darius fled the battlefield, ultimately abandoning his own family in Alexander’s hands. Alexander marched south into Syria and Phoenicia, intending to isolate the Persian fleet from its bases and weaken the fighting forces.

Alexander continued to capture city after city, and in one of the conquests he acquired Darius’s highly valued war chest. Darius wrote a letter to Alexander offering peace, but Alexander’s response required Darius’s unconditional surrender to him as the new Lord of Asia. While the seven-month battle of Tyre was in progress, Darius proposed a new offer to Alexander. In his letter, Darius offered to pay a ransom of 10,000 talents for his family, and, in addition, Darius agreed to cede all his lands west of the Euphrates. In a legendary exchange, Alexander’s trusted adviser Parmenio urged his king, “I would accept, were I Alexander.” Knowing the offer was inferior and unacceptable, the Macedonian general famously responded, “I would too, were I Parmenio.”

The capturing of Tyre in 332 b. c. e. is considered to be one of Alexander’s greatest military achievements in which the victory resulted in great bloodshed and the surviving women and children were sold into slavery. After conquering Egypt, completing his control of the eastern Mediterranean coast, Alexander returned to Tyre in the spring of 331 b. c. e. As part of his administrative duties, Alexander appointed a Macedonian satrap for Syria and prepared for his advancement into Mesopotamia. While attempting a clever military maneuver, Alexander crossed northern Mesopotamia toward the Tigris River rather than taking the direct route down the river to Babylon. Despite Alexander’s cautious efforts, however, Darius was informed of this maneuver from an advance force, and Darius marched up the Tigris to oppose him. Nevertheless, in the decisive Battle of Gaugamela, Alexander pursued the defeated Persian forces for 35 miles to Arbela. In arguably the most brilliant military maneuver of Alexander’s career, Alexander realized how he could defeat the Persian troops, and with his Companion Calvary command he was able to break through the Persian line and make charge straight for Darius’s chariot. As part of Alexander’s military maneuver, the Companion Calvary was Alexander’s elite cavalry and guard, and the cavalry worked as the main offensive support of his army. In a metaphor to describe the style of Greek combat of the time, the Companion Calvary would be used as the hammer while Alexander’s phalanx-based infantry would serve as the anvil. The phalanx would work to confine the enemy in place, and the Companion Calvary would move in from behind or from the side to attack the enemy. The implementation of this military maneuver gave Alexander the victory at Gaugamela, which finally resulted in his defeat of Persia and thus opened the gates for his control of Asia.

While it is not clear whether Alexander and Darius faced each other on the battlefield, it is at least certain that once Darius realized his enemy was frighteningly close, Darius retreated to evade the clutches of Alexander. Not afraid of the pursuit and with the taste of victory tantalizingly within his grasp, Alexander continued to chase Darius as he fled the battlefield. Alexander had long sought after Darius, and he knew the importance of capturing the king alive so Darius could remain a figurehead for the conquered Persians and thus keep them in control. However, when Alexander’s military council was informed of troubling news with Parmenio and the Greek army, the members urged him to return to the battlefield, where he was more needed. As difficult as it was to cease the chase of his enemy, Alexander reluctantly ended the pursuit of Darius and acknowledged the importance of returning to his troops engaged in combat. Darius narrowly escaped Alexander’s clutches, and he exiled himself into Media with his Bactrian cavalry and Greek mercenaries. The Battle of Gaugamela can legitimately be regarded as the greatest military achievement for Alexander, and the defeat allowed Alexander to subjugate the city of Babylon. While not capturing Darius physically, the defeat of the Persian army propelled Alexander to assume his desired title as the Lord of Asia. As an even more astounding feat at the Battle of Gaugamela, historical records indicate that of Alexander’s forces, approximately only 100 men and 100 horses were killed in the battle or consequentially died from exhaustion. Yet for the Persian army, more than 300,000 were slain in the battle, and even more than this amount were taken as prisoners.

Alexander had previously captured Darius’s wife and children, not to mention his battle spear and war chest of money, yet Alexander gentlemanly agreed to let Darius’s family live unharmed at the capital. Continuing to march across the continent, Alexander ceremonially burned down the legendary palace of Xerxes at Persepolis, convinced it would be a symbolic gesture that the Panhellenic war of revenge was at an end. Historians contend, however, that the burning of the palace brought shame to Alexander the next morning when he realized what he had done. The following spring, Alexander marched north into Media and occupied its capital, Ecbatana. The Thessalians and Greek allies were sent home, and Alexander continued his personal war against Darius. Alexander would not relent, and his final defeat of the Persians would be marked by his successful capture of Darius. Furthermore, Alexander feared that additional delay would give imposters the opportunity to state they were Darius, as it was quite common at that time for imposters to pretend they were the genuine ruler and thus cloud his defeat of the true Darius by chasing after charlatans. In his continuation of his quest for Darius, who had retreated into Bactria, by midsummer Alexander set out for the eastern provinces at a high speed. At the same time, Bessus, reigning as the satrap of Bactria and companion to the fleeing Darius, grew frustrated and tired of Darius’s inability to fight. Bessus believed that since Darius was unable to remain in control of the throne, he should no longer serve as ruler of the Persian Empire. Bessus was consumed with resentment for their current predicament, and he initiated the revolt in which he and his cohorts killed Darius and chained his dead body to a wagon on the side of the road. In spite of their rivalry, Alexander ordered Darius’s body to be buried with due honors in the royal tombs at Persepolis. Turning his anger onto a new enemy, Alexander now vowed to defeat Bessus for robbing him of the pleasure to capture Darius alive.

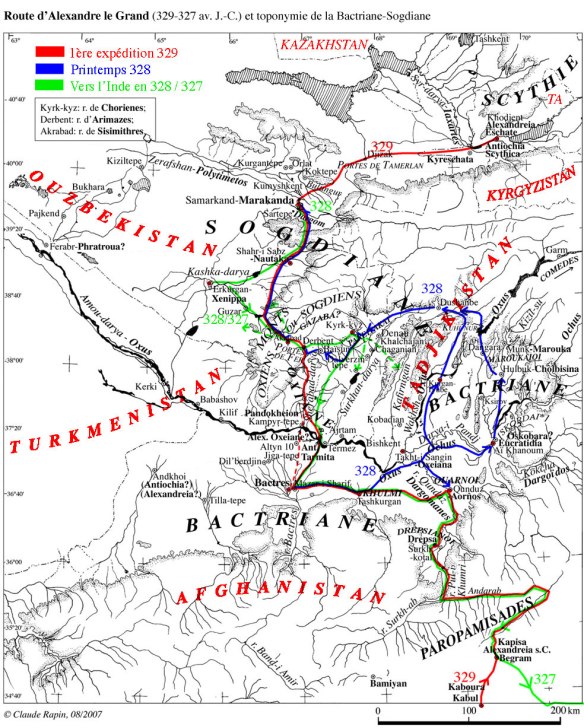

The death and unofficial defeat of Darius in 330 b. c. e. was significant in the formation of Afghanistan. The defeat of the Persian king was the last obstacle to Alexander’s self-desired title as the Great King, and soon after Alexander’s Asian coinage titled him the Lord of Asia. Alexander continued his advancement to the Caspian Sea, and in Aria he agreed to let the ruling satraps remain in place. In the location now known as modern Herat of Afghanistan, he established the city of Alexandria of the Arians. During the winter of 330-329 b. c. e., Alexander advanced farther into Afghanistan. Alexander and his army marched up the Afghan valley of the Helmand River and over the mountains past modern Kabul. Here in the country of the Paropamisadae, the great Macedon founded Alexandria by the Caucasus. In continuing the quest for Bessus, the army crossed the mountains of the Hindu Kush and proceeded northward over the Khawak Pass. In spite of the tired army, the food shortages, and the harsh terrain of the “Hindu killer” mountains, Alexander brought his army to Drapsaca in pursuit of Bessus and what remained of the Persian army. As Bessus worked to escape Alexander by moving beyond modern Amu Darya, Alexander marched his army toward the region of Bactra-Zariaspa, known as modern Balkh in Afghanistan. Bessus was counting on allegiance with the satrapies in the regions of Afghanistan along with other principalities to join him in the resistance against Macedonian control. After passing over the Oxus River, Alexander sent his general Ptolemy to track down Bessus, who at this point was removed from power by the Sogdian Spitamenes. Bessus was captured, flogged, and sent to Bactra to accept his fate for his crimes, for which the Persian method of punishment at the time was to cut off the nose and ears of the offender. After Bessus received this Persian punishment, he was publicly executed at Ecbatana.

With Bessus now captured, punished, and executed, Alexander continued his quest to defeat the remaining Persian Empire, and accordingly he turned his forces to concentrate on the defeat of Oxyartes, the companion of Bessus and reigning satrap of Bactria. In 327 b. c. e., Alexander still had one province of the Persian Empire to defeat, located in Balkh of Bactria in Afghanistan. In fear of the wrath of Alexander, Oxyartes secured his wife and his daughter Roxana in the fortress of Sogdian Rock, a fortress that allegedly could only be captured by “men with wings.” Alexander arrived at the fortress and requested the surrender of Oxyartes and consequently the remaining Persian Empire. With no response from the king, Alexander scoured his troops for volunteers to climb the steep walls of the fortress. On his capture of the fortress of Sogdian Rock, Alexander gazed on Roxana for the first time, a woman whose beauty, legend has it, overwhelmed him. Completely taken with her, Alexander made the daughter of Oxyartes his bride, and the marriage was also an attempt to subdue the Bactrian satraps rule to Alexander. After the wedding, Alexander moved forward with conquering India the then known “far end of the world.” In 327 b. c. e., Alexander left Bactria with a revitalized army and marched forward into the world’s end. Alexander’s dream of completing his empire could not happen fast enough as he sought to march his army to the last corner of India. After again crossing the treacherous terrain of the Hindu Kush Mountains, Alexander thought it best to divide his forces. In performing what he considered to be a maneuvering advantage the great general sent a portion of his army through the Khyber Pass in Afghanistan, and Alexander led the remaining troops through the hills to the north. Alexander did not have much knowledge of India’s vastness beyond the Hyphasis, but the young Macedon was fervent to discover the extent of his soon-to-be-completed empire. The army faced many difficulties after the tiring and exhausting march to the Hyphasis, and eventually the troops were weak from hunger and exhaustion, and these fatigued souls refused to go any farther. Alexander was overcome with anger, but his troops pleaded with him to return home. Finding the army adamant in their stance and the exhaustion and death tolls rising, Alexander agreed to cease the exploration and turn back into Afghanistan. While returning through the Mulla Pass, Quetta, and Kandahar into the Helmand valley of Afghanistan, the extensive attempt at advancement into India took a severe toll on the army, and as such Alexander’s march to the world’s end proved disastrous. The barren desert, lack of water, and shortage of food caused great distress to his troops, and as a result many of Alexander’s followers perished.

Despite not achieving much victory in India, Alexander continued to battle and to expand his empire. After conquering region after region and subjugating different races along the way, Alexander believed that unification of the races would be necessary to successfully amalgamate the empire. Thus, Alexander began his plans for racial fusion after conquering Susa in 324 b. c. e. Alexander celebrated the seizure of the Persian Empire by instituting his custom of combining the Macedonians and Persians into one master race. Alexander believed that uniting the races would make the Persians on equal terms not only in the Greek army but also as satraps of the provinces. In supporting this challenging endeavor, Alexander encouraged his Macedonian officers to take Persian wives, as he himself had married the Persian Roxana. This policy was harshly begrudged by the Greeks and as a consequence brought increasing friction to Alexander’s relations with his Macedonians. His determination to incorporate Persians on equal terms with the Macedonians in both the army and the administration of the provinces was severely resented. Macedonians interpreted this as a threat to their own privileged position, especially after many Persian youths received a Macedonian military training. As a further insult to the Macedonian warriors, Persian nobles had been accepted into the royal cavalry bodyguard.

Alexander was widely respected, and history would award him the title of the greatest military general of all time. Alexander’s energetic personality, strong determination, and ability to push for excellence with both himself and his army earned him respect and admiration. However, Alexander’s plans for racial synthesis were a complete failure since the Macedonians rejected the concept of cultural synthesis, and the customs of the Greeks would remain dominant. Alexander successfully maintained loyalty throughout his reign and it was only in his unsuccessful attempt to conquer India that Alexander failed to preserve unfaltering allegiance.

In the summer of 323 b. c. e. in Babylon, Alexander was quite suddenly taken ill after a banquet. Historians debate whether Alexander was poisoned or simply died of a natural illness. Alexander clung to life for 10 days, and on June 13 he died at the age of 33. Alexander had reigned for more than 12 years, and his body was eventually placed in a golden coffin in Alexandria. In spite of Alexander’s short reign, he had a profound impact and long-lasting influence on the history of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East.

In Afghanistan, Alexander would create many cities, establish a new political structure, and bring a great deal of Greek influence to the region. Alexander’s short-lived empire further attests to the incomparable warrior-like mentality of the early Afghans, for not even the great Alexander was able to fully conquer and control their land. The kingdom was divided after his death and Afghanistan was geographically separated by the Hindu Kush Mountains. The Seleucid Empire reigned the lands to the north if the mountain range while the Mauryan dynasty of India ruled southern Afghanistan.