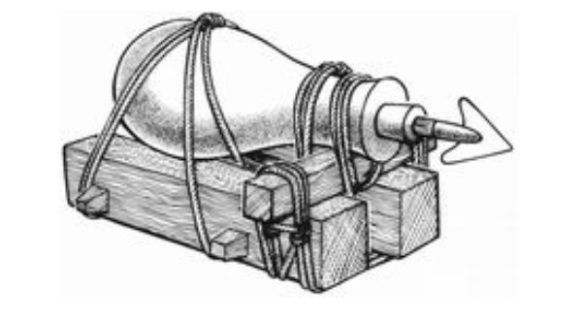

The pot de fer, known to the Arabs as midfa, was the ancestor of all subsequent forms of cannon. Materials evolved from bamboo to wood to iron quickly enough for the Egyptian Mamelukes to employ the weapon against the Mongols at the battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, which ended the Mongol advance into the Mediterranean world. A wooden cup on the end of the arrow trapped gas behind the projectile.

MAMLUK ENGINEER WITH MIDFA

A certain al-Hassan al-Rammah describes and illustrates the Midfa in a work of c. 1280-1290. It was clearly an early firearm, made of wood with a barrel only as deep as its muzzle width, used to fire Bunduks (?bullets) or feathered bolts. The charge filled a third of the barrel and consisted of a mixture of 10 parts saltpetre (Barud), 2 parts charcoal, and 1½ parts sulphur.

The actual discovery of gunpowder is a dubious distinction which has been variously claimed for Chinese, Indians, Byzantines, Arabs, Germans and Englishmen, but the name of the discoverer and date of actual discovery remain uncertain. The date of the application of gunpowder to a projectile-firing weapon is even more hazy, but if the dating of this Mamluk ms. is correct then this source is certainly amongst the earliest pieces of evidence outside of China. This weapon was probably no more than an experimental device of the Royal Arsenal and may never have seen active service, though the late-13th century chronicler Ibn ‘Abd al-Zahir remarks that for the siege of al-Marqab in 1285 ‘iron implements and flame-throwing tubes’ were issued by the royal arsenals, and one wonders whether any of the Mamluk engineers armed with ‘naptha tubes’ at Salamiyet in 1299 (apparently mounted), or storming the breaches of Acre in 1291, might have actually carried such weapons. It has to he admitted that hand-siphons like those used earlier by the Byzantines seem more probable.

‘Midfa’ was also the name applied to the earliest known Mamluk cannons, dating to 1366 or possibly 1340 (late dates considering the apparent earliness of the weapon described here).

The first use of explosive gunpowder and cannon is another critical issue in the history of civilization. Gunpowder was first known in China but the mixture used was weak and not explosive. The proportions of the ingredients were not the right ones for cannon and the purity of the nitrate was not adequate because of the lack of a purification process.

In the thirteenth century the military engineer Hasan al-Rammah (d 1295 AD) described in his book al-furusiyya wa al-manasib al-harbiyya (The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices) the first process for the purification of potassium nitrate. The search for some comparable weapon drove scientists and inventors such as the thirteenth century English scholar Roger Bacon and the fourteenth-century Korean scientist Choe Mu-Seon to extremes of experimentation.

The Chinese had first appreciated the explosive effects of the `fire drug’ (huo yao) – a mixture of sulphur, saltpetre and other ingredients – as far back as the ninth century. At first, they used the gunpowder mixture in the construction of their own version of `fire arrows,’ simple rockets, and in what would be called today `shock grenades’, to stun and confuse an enemy. In between its Chinese inventors and European developers were the Arab traders who brought the gunpowder mixture to the West. It is not certain who first thought of enclosing the explosive to drive a projectile, but the Arab accounts refer to a weapon called a midfa – a section of reinforced bamboo (and later iron pipe) driving an arrow with a gunpowder charge.

The raiders besetting the kingdom of Korea were Japanese pirates called wako, but the need was the same. With the Chinese keeping a similar control over the knowledge of gunpowder that the Byzantines did with Greek fire, the Korean scientist Choe Mu-Seon had to combine curiosity, persistence and great resourcefulness. Hearing that a travelling Chinese merchant knew the proper proportions of saltpetre and sulfur to charcoal, Mu-Seon was able to bribe the exact recipe out of him and produce his own versions, which he refined, like Roger Bacon, through experimentation.

Like other inventors throughout the world, Choe Mu-Seon found government support in an era long before the concept of capitalized invention had dawned in any but a military context. Demonstrations before the Korean royal court led to the first weapons laboratory since the original Museum at Alexandria, and resulted in improved leaching methods for nitrates from soil, a rocketfiring cart and a Korean version of the cannon. Preference or practicality drove the Korean line of development into artillery and away from infantry weapons. This choice would find considerable vindication before two centuries had passed.

The process involves the lixiviation of the earths containing the nitrate in water, adding wood ashes and crystallization. Wood ashes are potassium carbonates which act on calcium nitrate which usually accompany potassium nitrate to produce potassium nitrate and calcium carbonate. The carbonates are not soluble and are precipitated.

Al-Rammah deals extensively in his book with explosive gunpowder and its uses. The estimated date of writing this book is between 1270 and 1280. The front page states that the book was written as “instructions by the eminent master Najm al-Din Hasan Al-Rammah, as handed down to him by his father and his forefathers the masters in this art and by those contemporary elders and masters who befriended them, may God be pleased with them all”. It is unmistakable from this statement that Al-Rammah compiled inherited knowledge. The large number of gunpowder recipes and the extensive types of weaponry using gunpowder indicate that this information cannot be the invention of a single person, and this supports the statement of the front piece in his book. If we go back only to his grandfather’s generation, as the first of his forefathers, then we end up at the end of the twelfth century or the beginning of the thirteenth as the date when explosive gunpowder became prevalent in Syria and Egypt.

The book contains 107 recipes for gunpowder. There are 22 recipes for rockets (tayyarat, sing, tayyar). Among the remaining compositions some are for military uses and some are for fireworks. The gunpowder composition of seventeen rockets was analyzed, and it was found that the median value for potassium nitrates is 75 percent.

The ideal composition for explosive gunpowder as reported by modern historians of gunpowder is 75 percent potassium nitrate, 10 percent sulphur, and 15 percent carbon. Al-Rammah’s median composition is 75 nitrates, 9.06 sulphur and 15.94 carbon which is almost identical with the reported ideal recipe.

Analysis of the composition of explosive gunpowder in several other Arabic military treatises of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries gave results similar to those of al-Rammah. These included the composition of gunpowder in the first cannon in history that was used, according to the military treatises, to frighten the Tatar armies in the battle of ‘Ayn Jalut in 1260.

The correct formula for the explosive mixture was not known in China or Europe until much later.

The Arabs in al-Andalus used cannon in their conflicts with the crusading armies in Spain and their first knowledge of the art was effective in their encounters. But ultimately the Muslim technology of gunpowder and cannon was transferred to Christian Spain and was used by them it the last encounters with the Muslims. From Christian Spain this technology reached Western Europe. We have mentioned in Part I of this article how the Earls of Derby and Salisbury, who participated in the siege of al-Jazira (1342-1344), took back with them the secrets of gunpowder and cannon to England.