As early as at his last frustrating meeting with Alexander, at Erfurt four years earlier, Napoleon’s more intuitive self had been warned of the true state of their apparently cordial relationship. On a raft moored in the middle of the Niemen at Tilsit, each had tried to out-charm the other – and Napoleon, undoubtedly, had come off best. But by 1810, privily encouraged by Talleyrand’s murmurs that ‘the giant has feet of clay’, it had been the Tsar who’d begun to call the tune. And one night Napoleon’s First Valet Constant Wairy, asleep as usual in the next room, had been awakened by ‘dull and plaintive cries, as of someone being strangled’. Jumping out of bed, ‘with such precautions as my alarm permitted’ he’d opened the door:

‘Going over to the bed, I saw His Majesty lying across it in a convulsive posture, his sheets and bedcover thrown off and all his person in a terrible state of nervous constriction. Inarticulate sounds were coming from his open mouth, his chest seemed deeply oppressed, and he was pressing one fist against the hollow of his stomach. Terrified to see him like this, I speak to him. When he doesn’t reply, I shake him lightly. At this the Emperor wakes up with a loud cry and says: “What is it? What is it?” [And then, interrupting Constant’s apologies] “You’ve done quite right, my dear Constant. Ah! my friend, what a horrible nightmare! A bear was ripping open my chest and tearing my heart out.” Whereupon the Emperor got up and walked to and fro in the room while I was rearranging his bedclothes. He was obliged to change his shirt, the one he had on being drenched in sweat. The memory of this dream followed him a very long while. He often spoke of it, each time trying to extract different deductions from it and relate it to circumstances.’

That Napoleon has forseen the coming campaign’s exceptional difficulties, at least in part, there is no question. None of his others have called for such meticulous planning. Or for so huge a mobilization of men and resources. ‘Without transport,’ he’d written in 1811 to his stepson Eugène de Beauharnais, Viceroy of Italy, ‘all is useless’. And as early as June that year his ‘geometrical mind’ had begun wrestling with the problem.

Unprecedented mobility had always been a condition of Napoleonic blitzkrieg. And therefore the French armies had always lived off the rich lands they had conquered. But the far north was a different matter, as Sergeant Jean-Roch Coignet, the 2nd Guard Grenadiers’ little drill instructor, all too vividly remembers. In Poland’s sandy quagmires in 1806

‘we’d had to tie on our shoes with string under the insteps. Sometimes, when the bits of string broke and our shoes got left behind in the mud, we had to take hold of our hind leg and pull it out like a carrot, lift it forward, and then go back and look for the other one. The same manoeuvre over and over, for two days on end.’

Neither were Lithuanian roads – insofar as they existed – like western European ones. ‘In this part of the world,’ the Prussian lieutenant H.A. Vossler of Prince Louis’ Hussars will soon be discovering, ‘all heavy transportation normally goes by sledge in winter. Roads aren’t as important as in more southerly climes.’

Although the French army has a Supply Train, it consists of only 3,500 men and 891 vehicles, certainly not enough to maintain an invasion force of at least a third of a million men. For that’s what’s in question. One day, taking aside his War Minister Clarke on the terraces of St-Cloud, Napoleon had confided to him: ‘I’m planning a great expedition. The men I shall get easily enough. The difficulty is to prepare transport.’

Huge quantities of rice, flour and biscuit will have to be assembled and paid for. Well there’s gold and enough for that! The gold millions extorted from Prussia as reparations for her attack on him in 1806 and, in 1805 and 1810, from Austria, are lying in the Tuileries cellars, to which only Napoleon himself and his infinitely hard-working, enormously capable Intendant-General Pierre Daru have keys. By March 1812 he’s hoping to have 270,000 quintals of wheat, 12,000 of rice, 2,000,000 bushels of oats, equivalent to 20 million rations of bread and rice – enough for 400,000 men and 50,000 horses for 50 days. Since armies are also apt to be thirsty and brandy is also needed for amputations, on 29 December he has already ordered the Minister of Administration of the Army to buy at Bordeaux ‘28 million bottles of wine, 2 million bottles of brandy’, i.e., 200 days’ rations of wine and 130 of brandy for 300,000 men.

But the transport question remains. On such terrain will the existing 1,500 large-wheeled battalion wagons, each drawn by eight horses and capable of carrying 10,000 rations, suffice to feed the army for 25 days, the time needed for his swift campaign? Although really too heavy, h’d at first assumed that they would. But next day he had thought the matter over. If such a wagon is

‘“loaded with biscuit, it has to be in barrels, otherwise the biscuit crumbles, and the men complain. Nor is it suitable for grain, flour, oats, bales of hay, or barrels of wine or brandy. So each battalion must keep its wagon for its normal needs. All others must be replaced by good carriers’ wagons with big wheels, each drawn by eight horses and driven by four men, or, if need be, by three,”

all of them, preferably, foreigners. On 4 July 1811, writing to the head of his supply corps, he’d come to the conclusion that a wholly new, much lighter kind of cart must also be invented, “normally designed to carry 4,000 rations, or if necessary 6,000, and driven by two men and four horses’. Since even these can’t be counted on to cope with the terrain at its worst, an even lighter type of cart must be designed, drawn by a single horse, used to walking nose to tail, “so that only one man will be needed for several carts”. Oxen, too, will be useful. Even when prodded on by conscripts not used to wielding a goad, they can at least eat grass by the wayside before themselves being eaten.

How long will the biggest army in the history of European warfare be able to sustain itself amid Lithuania’s conifer forests? Long enough, at least, Napoleon has calculated, to roll up and annihilate its enemy.

To defend their vast country the Russians, he knows, have two armies, plus a third, currently engaged fighting the Turks in Moldavia. The First West Army is commanded by Barclay de Tolly, a Lithuanian of Scottish descent who, remarkably, had once served in the ranks and who since the Friedland disaster, as Minister for War, has modernized the Russian army on French lines. It’s being concentrated around Vilna (Vilnius). The Second West Army, commanded by the fiery and temperamental Georgian Prince Bagration, is cantoned further south around Grodno, 75 miles further up the Niemen. By driving a wedge between Barclay and Bagration in a surprise attack of the kind he has so often launched before, Napoleon, with the reputation of his own invincibility and no fewer than ten army corps and three ‘reserve’ cavalry corps at his disposal, is planning to defeat them in detail. And if all goes well the campaign will indeed be over within a couple of weeks.

But how, on a given day in the summer of 1812, concentrate the Grand Army, with its 150,000 horses and 1,000 guns, on the banks of the Niemen – frontier between Poland and Russian Lithuania? That’s the immense logistic problem he has set himself. And on which day? Neither too early – summer comes late to the North and the corn must be ripe for fodder. Nor too late; with autumn coming on in mid-August that would be to risk the very winter campaign so feared by Colonel Ponthon. Midsummer Day should be about right.

All over Europe units are being reinforced. Regiments normally four battalions strong are being increased to five. In its Courbevoie barracks outside Paris the infantry regiments of the Imperial Guard – an entire crack army corps 50,000 strong – are being brought up to scratch. Two whole companies of oldsters, ‘only too happy to be assigned such pleasant duties’, are being weeded out from the 2nd Grenadiers and replaced by ‘superb men who keep arriving daily’ from the Line, for which Guard NCOs are in turn being trained to take commissions. While teaching a squad of officer cadets their new command duties Sergeant Coignet is having them teach him his ABC, while the adjutants-major train them in theory. Such is the system, and

‘Napoleon himself checked up on the results. For fifteen days a hundred men, presided over by the adjutants-major, were making up cartridges. To avoid any danger of an explosion they had to wear shoes without hobnails, taken off and inspected every two hours. We made up 100,000 packets. The moment this harvest was in – major manoeuvres in the plain of St-Denis, and reviews at the Tuileries, together with sizeable artillery parks, wagons and ambulances! The Emperor had them opened and himself climbed up on a wheel to make sure they were full.’

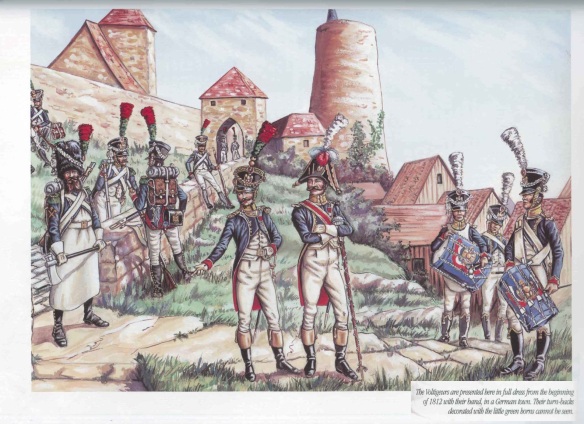

The regiments of the Young Guard, too, are hurriedly being brought up to strength. Its officers, taken from the Old Guard, will still draw their higher pay; but otherwise its regiments are really no different from those of the Line. Now it’s to consist of thirteen regiments of tirailleurs, thirteen of voltigeurs, one of fusilier-grenadiers, one of fusilier-chasseurs, one of flankers, one of éclaireurs, and one of national guards – ‘ten distinct denominations for infantry units armed in exactly the same way and all carrying the same model of standard-issue musket’. Paul de Bourgoing, a well-educated young lieutenant of the 5th Tirailleurs just back from fighting in Spain, is present as the new recruits come in,

‘fifteen hundred young men in blouses, waistcoats, village costumes, or citizens of various provinces of the vast French Empire, traipsing over the vast barrack square to the rattle of sixteen drums. The drummers had almost all been taken from the Pupils of the Guard [a regiment consisting wholly of soldiers’ sons]. Almost all were Dutchmen. Some, from Amsterdam and Frisia, were only fifteen. Great care had been taken not to let any one company contain too many nationals of any one country: “That won’t be good either for discipline or for warfare,” my major told me. “Shuffle them together like a pack of cards! Choose the twelve men who seem to have the thickest beards, or are likely to grow them. Above all, don’t take any blondes or redheads;

only men with black beards, whom you’ll place out in front.”’

Carrying axes and wearing tall bearskins and white leather aprons, these are to be sappers and march at the head of the regimental column:

‘So I passed these 1,500 two-year-old chins in review as swiftly as possible. Most were still beardless. Scarcely 25 or 30 of them were destined ever to see their maternal hearths again.’

On the Elbe, meanwhile, an Army of Observation, soon to become I Corps, is being drilled to a degree of efficiency ‘almost equalling the Imperial Guard’ under its fearsomely disciplinarian commander, Marshal Davout, Prince of Eckmühl. One of its strongest infantry regiments, the 85th Line, has spent the winter in the strongly fortified town of Glogau, ‘as in a besieged city’. Its 1st battalion’s portly 2nd major C.F.M. Le Roy6 is a staunch democrat who regards all blue-blooded persons with contempt, Napoleon as ‘an enterprising genius’ and the Russians as barbarians. After ‘deciding to be born in the midst of a nation execrated by all others’, he’d begun his military career ‘by chance’ as a conscript in 1795 but ‘continued it by taste’. During that winter of 1811/12 he has been amused to see how at the Grand Casino the wives of the local nobility, ‘without fear of besmirching their sixteen quarterings of nobility’ have been happy to gamble and dance with the young officers; and, not least, how ‘more than one felt an impulse to fall into [the] Line – and enjoyed doing so’.

In Southern Germany, too, the various principalities of the French-dominated Confederation of the Rhine are reluctantly supplying fresh contingents to General Vandamme’s VIII Corps. Meanwhile Jerome Bonaparte, King of Westphalia, Napoleon’s troublesome youngest brother, though destitute of military experience, is no less reluctantly preparing himself to assume overall command both of it, as well as Prince Poniatowski’s V (Polish) Corps and General Reynier’s Saxons (VII). None of these sacrifices, though unwelcome, are novel. In 1806 the little duchy of Saxe-Coburg had been overrun by the bluecoats; and only ten months have gone by since the kind-hearted Duchess Augusta was pained to see

‘the fragments of our poor little contingent return from Spain – eighteen men out of 250! Most of the losses haven’t been due to actual fighting, but mainly to disease, scarcity and neglect, added to the hardships caused by the Spanish climate. Half the town turned out to meet the survivors,’

she’d noted in her diary. Now she’s depressed to see a fresh contingent march out, this time northwards.

What is their destination? Coignet, in Paris, may not know; but all these tens of thousands of conscripted Germans certainly do. Writing home to his family for some pocket money for this new campaign, one of Davout’s corporals hears it’s going to be India, a country evidently populated by monkeys [‘aux Singes’ = aux Indes]. Which way? Via Russia, of course, whose emperor is, for the third time, to be ‘taught a lesson’.