Up to 1596 there was no question of international politics which did not somehow involve the Ottomans.

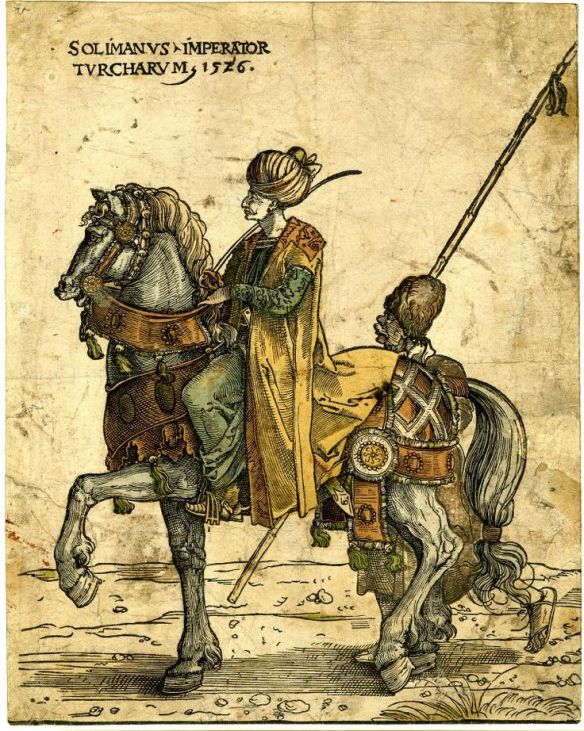

In 1519 the Habsburg Charles V and Francis I of France were candidates for the crown of the Holy Roman Empire, and both promised to mobilize all the forces of Europe against the Ottomans. The Electors considered Charles V more suited to the task, and shortly after the election, in March 1521, these two European rulers were at war with each other. Europe, to the great advantage of the Ottomans, was divided, and Süleymân I chose this time to march against Belgrade, the gateway to central Europe. Belgrade fell on 29 August 1521. On 21 January 1522 he captured Rhodes, the key to the eastern Mediterranean, from the Knights of St John.

When Charles V took Francis prisoner at Pavia in 1525, the French, as a last resort, sought aid from the Ottomans. Francis later informed the Venetian ambassador that he considered the Ottoman Empire the only power capable of guaranteeing the existence of the European states against Charles V. The Ottomans too saw the French alliance as a means of preventing a single power dominating Europe. Francis I’s ambassador told the sultan in February 1526 that if Francis accepted Charles’ conditions, the Holy Roman Emperor would become ‘ruler of the world.’

In the following year Süleymân advanced against Hungary with a large army. The Ottoman victory at Mohács on 28 August 1526, and the occupation of Buda, threatened the Habsburgs from the rear. The Ottomans withdrew from Hungary, occupying only Srem, and the Hungarian Diet elected John Zapolya as King. At first the Ottomans wished to make Hungary a vassal state, like Moldavia, since it was considered too difficult and too expensive to establish direct Ottoman rule in a completely foreign country on the far side of the Danube. But the Hungarian partisans of the Habsburgs elected Charles V’s brother, Archduke Ferdinand, King of Hungary, and in the following year he occupied Buda and expelled Zapolya. Süleymân again invaded Hungary, and on 8 September 1529 again enthroned Zapolya in Buda as an Ottoman vassal. Zapolya agreed to pay an annual tribute and accepted a Janissary garrison in the citadel. Although the campaigning season was over, Süleymân continued his advance as far as Vienna, the Habsburg capital. After a three-week siege, he withdrew.

In 1531 Ferdinand again entered Hungary and besieged Buda. In the following year Süleymân replied by leading a large army into Hungary and advancing to the fortress of Güns, some sixty miles from Vienna, where he hoped to force Charles V to fight a pitched battle. At this moment Charles’ admiral, Andrea Doria, took Coron in the Morea from the Ottomans. Realizing that he now had to open a second front in the Mediterranean, the sultan placed all Ottoman naval forces under the command of the famous Turkish corsair and conqueror of Algiers, Hayreddîn Barbarossa, appointing him kapudan-i deryâ – grand admiral – with orders to cooperate with the French. Since 1531 the French had been trying to persuade the sultan to attack Italy and now they sought a formal alliance. In 1536 this alliance was concluded. The sultan was ready to grant the French, as a friendly nation, freedom of trade within the empire.1 The ambassadors concluded orally the political and military details of the alliance and both parties kept them secret. Francis’ Ottoman alliance provided his rival with abundant material for propaganda in the western Christian world. French insistence convinced Süleymân that he could bring the war to a successful conclusion only by attacking Charles V in Italy. The French were to invade northern Italy and the Ottomans the south. In 1537 Süleymân brought his army to Valona in Albania and besieged Venetian ports in Albania and the island of Corfu, where a French fleet assisted the Ottomans. In the following year, however, the French made peace with Charles. Francis had wished to profit from the Ottoman pressure by taking Milan, and when the emperor broke his promise he reverted to his ‘secret’ policy of alliance with the Ottomans.

In the Mediterranean Charles captured Tunis in 1535, but in 1538 Barbarossa defeated a crusader fleet under the command of Andrea Doria at Préveza, leaving him undisputed master of the Mediterranean.

When Francis again approached the sultan in 1540 he told Charles’ ambassadors, come to arrange a peace treaty, that he was unable to conclude a peace unless Charles returned French territory. There was close cooperation between the Ottomans and the French between 1541 and 1544, when France realized that peaceful negotiations would not procure Milan.

In 1541 Zapolya died, and Ferdinand again invaded Hungary. Süleymân once again came to Hungary with his army, this time bringing the country under direct Ottoman rule as an Ottoman province under a beylerbeyi. He sent Zapolya’s widow and infant son to Transylvania, which was then an Ottoman vassal state. Since 1526 Ferdinand had possessed a thin strip of Hungarian territory in the west and north, to which the Ottomans, as heirs to the Hungarian throne, now laid claim. In 1543 Süleymân again marched into Hungary with the intention of conquering the area, and at the same time sent a fleet of 110 galleys, under the command of Barbarossa, to assist Francis. The Franco-Ottoman fleet besieged Nice and the Ottoman fleet wintered in the French port of Toulon. In return, a small French artillery unit joined the Ottoman army in Hungary. This cooperation, however, was not particularly effective. With the worsening of relations with Iran Süleymân wanted peace on his western front. As in 1533, he concluded an armistice with Ferdinand, which included Charles. According to this treaty, signed on 1 August 1547, and to which Süleymân made France a party, Ferdinand was to keep the part of Hungary already in his possession in return for a yearly tribute of thirty thousand ducats.

Three years later war with the Habsburgs broke out again when Ferdinand tried to gain control of Transylvania. The Ottomans repulsed him, and in 1552 established the new beylerbeyilik of Temesvár in southern Transylvania.

When the new king, Henry II, came to the throne in France, he realized the need of maintaining the Ottoman alliance in the struggle against Charles V. The French alliance was the cornerstone of Ottoman policy in Europe. The Ottomans also found a natural ally in the Schmalkalden League of German Protestant princes fighting Charles V. At the instigation of the French, Süleymân approached the Lutheran princes, urging in a letter that they continue to cooperate with France against the pope and emperor. He assured them that if the Ottoman armies entered Europe he would grant the princes amnesty. Recent research2 has shown that Ottoman pressure between 1521 and 1555 forced the Habsburgs to grant concessions to the Protestants and was a factor in the final official recognition of Protestantism. In his letter to the Protestants, Süleymân Intimated that he considered the Protestants close to the Muslims, since they too had destroyed idols and risen against the Pope. Support and protection of the Lutherans and Calvinists against Catholicism would be a keystone of Ottoman policy in Europe. Ottoman policy was thus intended to maintain the political disunity in Europe, weaken the Habsburgs and prevent a united crusade. Hungary, under Ottoman protection, was to become a stronghold of Calvinism, to the extent that Europe began to speak of ‘Calvino-turcismus’. In the second half of the sixteenth century the French Calvinist party maintained that the Ottoman alliance should be used against Catholic Spain, and the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of the Calvinists infuriated the Ottoman government.

It should be added that at first Luther and his adherents followed a passive course, maintaining that the Ottoman threat was a punishment from God, but when the Turkish peril began to endanger Germany the Lutherans did not hesitate to support Ferdinand with military and financial aid; in return they always obtained concessions for Lutheranism. Ottoman intervention was thus an important factor not only in the rise of national monarchies, such as in France, but also in the rise of Protestantism in Europe.

Charles V, following the example of the Venetians, entered into diplomatic relations with the Safavids of Iran, forcing Süleymân to avoid a conflict with the Safavids, in order not to have to fight simultaneously in the east and west.

In 1533, however, Sheref Khan, the local lord in Bitlis in the frontier region, placed himself under Persian protection; at the same time, the shah’s governor in Baghdad came to an agreement with the Ottomans and war became inevitable. Süleymân signed an armistice with Ferdinand and marched on Iran at the head of his army. In this campaign of 1534–5 the Ottoman sultan took Tabriz and Baghdad and annexed Azerbaijan and Iraq. The local dynasts in the silk-producing areas of Gilan and Shirvan also recognized Ottoman suzerainty. In 1538 the Emir of Basra tendered his submission. By gaining mastery of the Persian Gulf, as well as of the Red Sea, the Ottomans controlled all the routes leading from the near east to India. By 1546 they had made Basra their second base after Suez for equipping fleets against the Portuguese; but in 1552 an Ottoman expedition failed to oust the Portuguese from the island of Hormuz which controlled the Persian Gulf.

When the Ottomans renewed the war in central Europe, the Persians counterattacked, and in 1548 Süleymân, for the second time, marched against Iran. This war lasted intermittently for seven years. By the Treaty of Amasya, signed on 29 May 1555, Baghdad was left to the Ottomans.

These Ottoman enterprises resulted, in the mid-sixteenth century, in a new system of alliances between the states occupying an area stretching from the Atlantic, through central Asia, to the Indian Ocean. In this way the European system of balance of power was greatly enlarged.

In the mid-sixteenth century the Russian Tsar, Ivan IV, occupied the Volga basin as far east as Astrakhan, threatening not only the Ottomans but also the khanates of central Asia. The Ottomans and the Uzbeks were drawn closer together. The central Asian khanates, unable to establish contact with the near east via Iran, usually used the route passing north of the Caspian Sea and leading to the Crimean ports. When the Russians gained control of this route, the central Asian khanates, and in particular the Khan of Khwarezm, made repeated calls to the Ottoman sultan to free this pilgrimage and trade route from Russian control.

The Ottomans had not regarded the great expansion of Muscovy, which until the 1530s had been a second-rate power in eastern Europe, as a danger in the north and had even supported an alliance between Muscovy and the khanate of Crimea against the Jagellonians, who threatened Ottoman sovereignty in the Crimea. In 1497 they had granted the Muscovites freedom of trade in the Ottoman Empire. But when in the 1530s the Grand Duke of Muscovy and the Khan of the Crimea went to war over the succession to the former territories of the Golden Horde in the Volga basin, the khan sought to awaken the Ottomans to the danger. It was only in the mid-sixteenth century that the Ottomans came to realize that the Russian advance threatened their position in the Black Sea basin and the Caucasus. After Ivan IV had assumed the title of tsar in 1547, he conquered and annexed the Muslim khanates of the Volga basin – Kazan in 1552 and Astrakhan in 1554–6 – advancing as far as the Terek river in the northern Caucasus, laying the foundations of the Russian Empire. In this region the tsar found allies among the Circassians and the Nogays; in the west in 1543, Petru Raresh, the voivoda of Moldavia, had sought the protection of Moscow; and finally, in 1559, the Cossack chieftain Dimitrash attempted to capture the fortress of Azov, the northernmost outpost of the Ottoman Empire. Following these successes, the tsardom of Muscovy succeeded the khanate of the Golden Horde as a first-class power in eastern Europe, spreading its influence into Ottoman domains in the Caucasus and the Black Sea region.

The Ottomans were able to turn their attention to the north only after 1566, when the war with the Habsburgs was no longer pressing. They conceived the bold plan of conveying an Ottoman army and fleet up the Don to the place where it flows closest to the Volga, where they would dig a canal between the two rivers, allowing the fleet to sail on Astrakhan down the Volga. The army and navy would cooperate in ousting the Russians from Astrakhan, the fleet then entering the Caspian Sea to assist the Ottoman army in Iran. The plan thus aimed to drive the Russians from the Volga basin and encircle Iran. This common danger united the two powers. In the winter of 1568 the tsar sent an envoy to Iran proposing an alliance against the Ottomans, and at the same time Pope Gregory XIII included the tasr and the shah in his plans for a crusade against the Ottomans. In 1569 the Ottoman attempt to dig the canal and besiege Astrakhan failed. The grand vizier, Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, had formulated the plan, and his rivals now proposed that the empire should concentrate its forces in the Mediterranean rather than continue the expensive and difficult war in the north. The tasr, for his part, knew that for the time being he could not hope to challenge the Ottomans.

To preserve his position in the Volga basin, the tsar adopted a peaceful and even friendly policy towards the sultan. The sultan left Kazan and Astrakhan in Russian hands but claimed Ottoman sovereignty over the khanate of the Crimea, the Circassian lands and the Caucasus. He demanded that the Russians withdraw from these areas and keep open the route from central Asia to the Crimea. But the sultan did not pursue this policy consistently or forcefully, since at this point he opened hostilities with western Europe in the Mediterranean, capturing Cyprus in 1570 and meeting with a crushing defeat at Lepanto in 1571.

Although the pope urged Russia to join Austria and Poland in attacking the Turks, the tsar remained at peace. Once established in the Volga basin, his policy was one of procrastination. He never evacuated the fortresses he had built in the northern Caucasus.

The Ottoman government left the struggle against Russia to its two vassals, the Khan of the Crimea and the Prince of Erdel (Transylvania). When the tsar stood for election as King of Poland in 1572, the Ottoman supported first Henry of Valois and then their vassal Stephen Batori, the Prince of Erdel. They succeeded in winning the Polish throne for Stephen, who then began a merciless struggle against Moscow, recovering all the tsar’s conquests in the west.