Military aviation in Thailand (Siam until June 1939) began in February 1912 when the Ministry of War sent three officers to France for pilot training. When they returned with eight French-built aircraft in November 1913, they were formed into the Army Aviation Section. On 27 March 1915, shortly after the airmen moved into their permanent home at a newly constructed airfield at Don Muang, outside Bangkok, the Ministry of War reorganized the Aviation Section into the Army Flying Battalion, under the command of French-trained Lieutenant Colonel Phraya Chalerm Akas.

King Vijiravudh was an enthusiastic supporter of the country’s growing air force. The monarch believed that aviation promoted national unity, fostered a spirit of modernity, and enhanced prestige in the world community. Army Chief of Staff Field Marshal Prince Chakrabonse Bhuvanart also led the way in promoting aeronautical development. In 1983, in grateful memory of his assistance during its formative years, the air force placed a statue of the prince in front of headquarters, inscribed “The Father of the Royal Thai Air Force.”

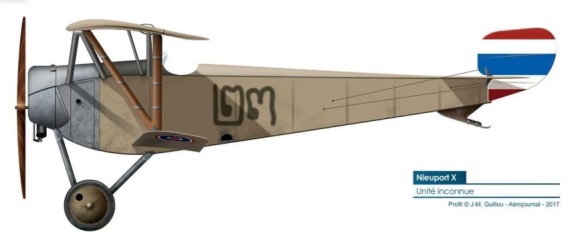

The government sent an aviation contingent to France in June 1918, but the war ended before the Siamese pilots entered combat. Nonetheless, the decision to assist the French not only increased the kingdom’s prestige but also allowed the air force to gain valuable experience. On 19 March 1919, the Flying Battalion became the Aeronautical Department of the Army, with three operational flying units (pursuit, observation, bombardment). A further reorganization took place on 1 December 1921 when the air component was renamed the Department of Aeronautical Service (more familiarly, the Royal Aeronautical Service). At the same time, the air force was designated as a special service with a separate budget, although it remained under the direct control of the commander in chief of the army.

The air force achieved complete independence on 9 April 1937 as the Royal Siamese (soon Thai) Air Force within the Ministry of Defense. The airmen adopted the blue uniforms and rank designations of the Royal Air Force. Group Captain Phra Vechayan Rangsarit became the service’s first commander.

Thailand’s long history of independence had not been free of the occasional conflict with Britain and France as they built and maintained their neighboring empires. During the later nineteenth century, during the reign of King Rama V, also called “Chulalongkorn the Great,” Thailand had fought a long-running war with France over parts of what are now Laos and Cambodia.

Though Thailand still possessed a figurehead monarch, it was ruled by Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram (also transliterated as Pibulsonggram), who occupied the seat of prime minister. Known generally as “Pibul” or “Phibun,” he was a fan of totalitarian governments such as Hitler’s Germany, and he had turned Thailand into one of Japan’s best friends – “ally” would be too strong a word – in the Far East. Under Phibun, Thailand had recognized Japan’s puppet government in Manchukuo, and had begun equipping its armed forces with Japanese-built ships and aircraft.

Following the Fall of France, Phibun was ready to seize the opportunity to take back what his country had lost. A virtual dictator since he had masterminded the 1932 coup d’état that curbed the power of the absolute monarchy of King Rama VII (aka Prajadhipok), Phibun had fended off revolts and threats to his rule through the years. He felt his army to be up to the task of taking on an overseas detachment of the army that had capitulated to the Germans in the space of a few weeks, and had surrendered a major city and a major port to the Japanese after a few days.

France was plunged into its second war of 1940 with a series of minor skirmishes in October, shortly after the Japanese had occupied the Hanoi–Haiphong area. The fighting escalated, with the two sides trading air raids. Much to the chagrin of French fighter pilots, the crews of the Royal Thai Air Force bomber fleet, which included Japanese-built Mitsubishi Ki-21s and Ki-30s, acquitted themselves very well in strikes against Vientiane and Phnom Penh.

In a major offensive in January 1941, the Royal Thai Army managed to recapture most of their objectives in Laos, and to make serious inroads against the French in Cambodia. The French were defeated in the climactic land battle on January 16, 1941, in the vicinity of Yang Dang Khum and Phum Preav, although French Foreign Legion artillery prevented the Thai forces from pursuing the retreating French troops.

The following day, however, the French won a significant naval victory in the battle of Ko Chang, off the coast of Thailand, near the Cambodian border. Admiral Jean Decoux had ordered the light cruiser La Motte-Piquet and several smaller gunboats to sail from Cam Ranh Bay, north of Saigon, to attack Thai ports near the Cambodian border. The flotilla was opposed by the Japanese-built coastal defense ship, HTMS Thonburi, as well as a pair of Thai torpedo boats. When the battle ended, both torpedo boats had been sunk, the Thonburi was dead in the water, and the French ships were still seaworthy.

France won the battle of Ko Chang, but lost the war. Less than a week later after the naval victory, Japan intervened to impose a ceasefire, which compelled France to leave Thailand in control of what it had captured, and left Prime Minister Phibun owing the Japanese a favor.

The Franco–Thai War (1940–1941)

The Armée de l’Air had, theoretically, around a hundred aircraft available for this conflict. The front-line aircraft amounted to some sixty aircraft of a variety of types including:

• thirty Potez 25 TOEs

• four Farman 221s

• six Potez 542s

• nine Morane-Saulnier M.S.406

• eight Loire 130 flying boats

The Royal Thai Air Force could muster around 140 aircraft, comprising:

• twenty-four Mitsubishi Ki-30 light bombers

• nine Mitsubishi Ki-21 medium bombers

• twenty-five Hawk 75Ns pursuit planes

• six Martin B-10 medium bombers

• seventy O2U Corsair light bombers

During the war with Thailand, the French launched just over 190 day missions and just over fifty night missions. The conflict ended on 28 January 1941. It had led to a number of key servicing problems for the aircraft. There were still nineteen French Moranes, of which only fourteen were serviceable. In addition, the French still had three serviceable Farman 221s, three out of four Potez 542s, only thirty-four of their fifty-four Potez 25s, nine of their twelve Loire 130s and none of their three Potez 631s available.

At the end of the hostilities, the German Armistice Commission allowed the transfer of aircraft reinforcements to Indochina. The Commission authorized the following aircraft to be transferred from Martinique:

• twenty-three Hawk H-75s

• forty-four Curtiss SBC-4s

However, the Japanese resisted this transfer and the plans to move the aircraft from Martinique were cancelled. As a result, Escadrille 2/596 was disbanded due to lack of spare parts for its aircraft and what remained of the unit, including both the pilots and the aircraft, were transferred to Escadrille 2/595. This disbandment and transfer took place in the middle of 1941.

The air force operated, without great enthusiasm, under Japanese direction until it shifted to support Thai resistance in the later stages of World War II. By war’s end, the RTAF had reached its nadir, with less the 50 percent of its aircraft in serviceable condition.

A new era dawned on 17 October 1950 when Thailand and the United States signed a mutual defense assistance agreement. The RTAF was reorganized along U. S. lines and reequipped with U. S. aircraft. It subsequently sent transport contingents to assist the United States during the Korean and Vietnam Wars. By 2000, the RTAF’s inventory consisted of 153 combat aircraft, including one squadron of F-5 A/Bs and two squadrons of F-16 A/Bs. Although not the largest air force in Southeast Asia, the well-trained RTAF stood ready to protect its country’s borders, as it had since its inception.

References

Young, Edward M. Aerial Nationalism: A History of Aviation in Thailand. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.