Hilfskreuzer 33 (Auxiliary Cruiser / Raider) – Pinquin

Käpitan-zur-See Ernst-Felix Krüder

The sinking of HMS Andania by the patrolling submarine U-A was assumed by the Admiralty to be a deliberate diversionary action to cover the breakout of another German auxiliary cruiser. Three of these, Atlantis, Widder and Thor, all converted merchantmen, had already escaped into the Atlantic. While the Admirals may have been wrong in the interpretation they put on U-A’s actions, they were right in assuming another raider was about to emerge.

As the Andania slipped beneath the waves off Iceland at dawn on 16 June 1940, a thousand miles to the south-east, in the Gulf of Danzig, the sun was well above the horizon and giving the promise of a fine, warm day to come. Swinging to an anchor in a quiet reach of the gulf close to the South Middle Bank, the German cargo liner Kandelfels was in the final stages of her metamorphosis from harmless merchantman to ship of war. Her company livery was last to go, the smart black hull and gleaming white upperworks disappearing under a coat of sombre wartime grey.

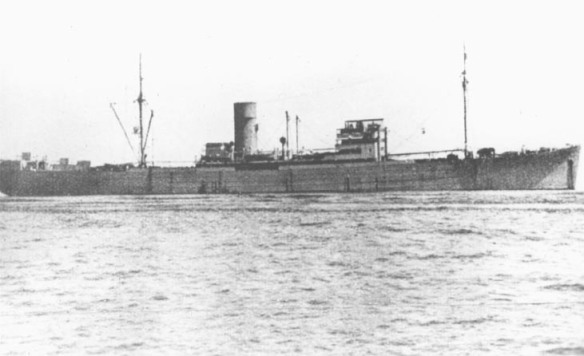

The 7766-ton Kandelfels, built at Bremen in 1936 for Deutsche Dampschiffarts Gesellschaft, better known as the Hansa Line, had arrived in Hamburg from India on 1 September 1939, just as German troops crossed the border into Poland, signalling the start of the second European bloodbath in the space of twenty-five years. As soon as the last sling of cargo from the East was winched up from the Kandelfels’ holds, she was requisitioned by the German Navy.

A modern, twin-screw ship with a service speed of 17 knots and a low silhouette, the Kandelfels was ideally suited for recruitment to the Kriegsmarine’s elite squadron of Hilfskreuzers (auxiliary cruisers) soon to be unleashed on Allied merchant shipping in the distant oceans beyond the reach of the U-boats. Unlike the highly vulnerable British AMCs, stop-gap ships used for patrol and convoy escort work, the role of the Hilfskreuzers – there would be nine in all – was predatory. Fast and heavily armed, they would emulate the buccaneers of old, hiding in the shadows out of reach of the enemy’s warships and aircraft, picking off victims wherever and whenever the opportunity arose.

Unfortunately, the German grand plan for the conquest of Europe was initially so successful that an adjustment of priorities was necessary. The Kriegsmarine’s ‘grey wolves’ went to the back of the queue. Conversion of the Kandelfels from merchant ship to auxiliary cruiser was originally scheduled to take three months, but, owing to more urgent demands on dockyard space and workers, it was 6 February 1940 before she emerged from the Bremen yard of Weser AG. as Hilfskreuzer 33. Outwardly, she was still a merchant ship, but behind counterweighted steel shutters, capable of being raised in two seconds, were six 5.9-inch guns. Concealed by false ventilators, watertanks or packing cases were one 75-mm, one twin 37-mm and four 20-mm guns. Similarly hidden were two twin 21-inch torpedo tubes, two 3-metre range finders, two 60-cm searchlights, and in her holds two spotter aircraft. A quick change of identity could be effected by telescoping the foremast, raising collapsible bulwarks to heighten the forecastle and raising or lowering collapsible sampson posts.

In theory HK 33 was a formidable warship, but in reality her 5.9s were 40-year-old guns taken from the obsolete pre-dreadnought battleship Schlesien, her smaller guns of similar vintage. Her scout planes, too, were obsolescent; single-engined, open-cockpit Heinkel HE 59 floatplanes, known to be notoriously unstable on the water. To ensure her future success, she was in need of a dedicated and experienced crew, men willing to take the calculated risk without too much thought for their own self-preservation. In this respect, at least, she was well blessed.

In command of HK 33 was 43-year-old Käpitan-zur-See Ernst-Felix Krüder, a slim, taciturn man, who had risen to command from the ranks – rare achievement in anyone’s navy at the time. Krüder, with twenty-five years service in the German Imperial Navy, was an expert in mine warfare and had seen action at Jutland and in the Black Sea in the First World War. Between the wars he had served in the Inspectorate of Officers’ Training and Education, where he had gained a great deal of experience in handling men. With a clear, analytical mind and the ability to improvise, Ernst-Felix Krüder was an excellent choice to take an auxiliary cruiser with a crew of 345 into the unknown. Many of that crew were naval reservists from the merchant ships; Krüder’s first lieutenant, Leutnant Erich Warning, had been Staff Captain of the North German Lloyd liner Bremen, while his navigator, Leutnant Wilhelm Michaelson, was lately in command of the 14,700-ton liner Steuben. Expertise in the way of the sea and ships Krüder’s men had in abundance, but whether they had the aggression and determination to make war remained to be seen.

It was the custom for commanders of German auxiliary cruisers to name their own ships, and when HK 33 was commissioned on 6 February 1940, in a brief ceremony on board Krüder christened her Pinguin (Penguin). It was a choice which puzzled his crew, but then, unlike their captain, they were not yet fully aware of their ship’s ultimate destiny.

Over the seven weeks that followed, the Pinguin carried out trials on the River Weser, testing her engines, exercising her guns and initiating her as yet untried crew into the strange world of a ship that was half merchantman and half warship. Any faults found in the ship and her equipment were rectified and, having taken on ammunition, coal and provisions, the Pinguin passed through the Kiel Canal into the Baltic. There, in sheltered waters away from prying eyes, Krüder drilled his gun and torpedo crews relentlessly, until they reached the peak he judged would give them a fighting chance against the best guns of the Royal Navy. At the same time mine-laying exercises were carried out and boats’ crews were sent away at every possible opportunity, so as to perfect the launching, handling and retrieval of their craft. These men would play a vital role in the Pinguin’s coming adventure.

The raider, her skills honed to perfection, returned to Kiel on 26 May for a few persistent faults in her gear to be corrected and to top up her oil, water and stores. She also took on board five live pigs, which would be fattened up on scraps from the galley during the voyage. As many crew members as possible were given shore leave, their last on German soil for many months, perhaps years, to come. She sailed on 10 June and again headed east into the Baltic, arriving in the Gulf of Danzig on the following day. She was given a berth in the naval base of Gotenhaven – as the Polish port of Gdynia had been renamed by Hitler – and worked under the cover of darkness taking on mines and torpedoes. On 17 June, anonymous in her new grey livery, the Pinguin left the Gulf of Danzig with 380 mines and 25 torpedoes in her holds. She was on her way to war.

In the early summer of 1940, although Britain stood alone and under threat of invasion, she had not lost control of the North Sea. Cruisers and destroyers of the Home Fleet constantly patrolled these waters, while the RAF kept watch overhead and submarines cruised below the surface. The primary object of these forces was to keep a lookout for an enemy invasion fleet, but any German ships venturing out into the North Sea, particularly lone merchantmen, did so at extreme peril. They could expect no help from their own navy; Germany’s capital ships remained firmly tied up in port, and her light naval forces had taken such a severe mauling at the hands of the Royal Navy in the Norwegian campaign that they could offer little protection.

The Pinguin, with all her potential to wreak havoc on the high seas, was a special case, and on the morning of the 18th she rendezvoused off Gedser, southern point of the Danish island of Lolland, with the minesweeper Sperrbrecker IV and the torpedo boats Jaguar and Falke. The latter were powerful, well-armed ships of over 900 tons. The Wolf-class Jaguar carried three 5-inch and four 37-mm guns, and the Falke, a Möwe-class boat, mounted three 4.1-inch and four 37-mm. Both carried six 21-inch torpedo tubes and had a top speed of 34 knots.

The small convoy passed through the Great Belt, the main channel between the Danish islands, in tight formation, entering the Kattegat at around 2100. At midnight, off the island of Anholt, Sperrbrecker IV left, and the Pinguin continued north at 15 knots with Jaguar and Falke keeping close company. British submarines were reported to be very active in this area and there could be no relaxing of vigilance.

The sun had already risen again when, at 0400 on the 19th, the three ships rounded the northern tip of Jutland and moved into the Skagerrak. It was a perfect early summer’s day, with a clear blue sky and a fresh easterly breeze kicking up white horses on the water. The air was clean and salt-laden, and, after the long months of preparation, the unrelenting pressures of the rigorous training programme, the crew of the raider faced the open sea eagerly, masters of their own destiny at last.

Air cover in the form of a Dornier 18 flying boat and two fighters materialized at the seaward end of the Skagerrak and remained overhead until darkness closed in again. At midnight Pinguin’s escort was reinforced by two M-class minesweepers, who brought with them a Norwegian pilot. The enlarged convoy then entered the deep-water channel behind the maze of islands that fringe the Atlantic coast of Norway. Protected by the islands, Pinguin was safe from Allied warships, but the channels, although deep, were narrow and tortuous, requiring careful navigation.

The port of Bergen was abeam to starboard at 0800 on the 20th and here Jaguar and Falke parted company, their escort duties over. The Pinguin and the two M-boats continued north, entering Sörgulen Fjord, some 50 miles north of Bergen, at 1630 that afternoon. The raider went deep into the fjord to an anchorage, while her escort remained on guard off the entrance.

Hidden from the prying eyes of enemy aircraft by the densely-wooded, steep-sided slopes of the fjord, the Pinguin took on the disguise it was hoped would see her clear of the coast and into the Atlantic. Over the next thirty-six hours, with the help of shore labour, the raider was transformed into the Russian cargo ship Petschura, port of registry Odessa, her hull black with the Soviet hammer and sickle prominent on her sides. When the work was finished, the disguise was convincing, but, should suspicions be aroused, German intelligence had established there was a real Petschura, conveniently laid up in Murmansk and unlikely to put to sea for some time.

The Pinguin left Sörgulen Fjord at 0100 on 22 June. She was now under the control of the Operations Division of the Seekriegsleitung (SKL), the German Naval Staff in Berlin. Her orders were to break out into the Atlantic through the Denmark Strait and from there to proceed south to a position off Cape Verde, where she would rendezvous with and refuel and provision Hans Cohausz’s U-A. Fresh from his success in sinking the Andania, Cohausz had already moved south to cover the approaches to Freetown, now being used as an assembly point for Allied convoys.

Having serviced U-A, Krüder’s orders were to round the Cape of Good Hope into the Indian Ocean, and there begin his campaign against Allied merchant shipping. It was anticipated that his harvest would be a rich one, for, in the absence of U-boats, the British considered the Indian Ocean to be a safe area and most merchantmen were sailing unescorted. Additionally, Krüder hoped to create further mayhem by mining the approaches to ports on the south and east coasts of Australia, and, later, the west coasts of India and Ceylon. And, as if this programme was not ambitious enough, at the end of the year the Pinguin was to sail south into the chill waters of Antarctica to attack the British and Norwegian whaling fleets. It was with this most southerly operation in mind that Krüder had named his ship.

The night was very black when the Pinguin weighed anchor and was escorted out of Sörgulen Fjord by her minesweepers. Under a heavily overcast sky with rain squalls sweeping in from the sea, the darkened raider made her way carefully down the fjord following the dimmed blue stern lights of the M-boats. Within the hour she was face to face with her first enemy of the war, the open sea. Clearing the mouth of the fjord at about 0200, she found herself heading into the teeth of a strong SW’ly wind, which rapidly increased to a full gale. Rain squalls severely restricted the visibility and, in a rising sea and swell, the ship took on an awkward corkscrewing movement. For many of her crew, having spent too long ashore or in sheltered waters, the curse of seasickness was an unwelcome visitor.

As for the ship herself, although she rolled and pitched heavily, the weather held no real dangers. The same could not be said for her escorts. M-17 and M-18 were both under 700 tons and narrow in the beam, and, while they may have been at home in the comparatively quiet waters of the Baltic, out here in the open Atlantic their seaworthiness was tested to the extreme. Plunging from crest to trough, rolling violently and shipping green water overall, the minesweepers took a severe pounding as they struggled to keep up with the bigger ship. Some 16 miles out of Sörgulen, after consultation with Krüder, they turned back and ran for shelter.

There is little complete darkness in these high latitudes in summer and by 0230 the sun was again climbing to the horizon, bringing a grey half-light to the overcast and revealing row upon row of white-topped waves marching in from the south-west. Pinguin, steering due west, had the wind and sea on the port bow, a distinct advantage, but Krüder, anxious to clear the coast before full daylight, was pushing his ship hard. With her twin 900 horsepower diesels thrusting her through the water at full revolutions, she had worked up to 15 knots, but was pounding heavily as she met the oncoming waves. Krüder feared he might soon be forced to slow down to avoid damage to his forward guns.

The decision was made for him when, just before 0300, a sharp-eyed lookout on the bridge spotted a periscope breaking the surface half a mile on Pinguin’s port bow. It was followed seconds later by the submarine’s conning tower. This looked like an accidental surfacing, for almost immediately both conning tower and periscope disappeared again in a welter of foam. Krüder sent his men to their action stations.

Prior to sailing from Sörgulen Fjord, Krüder had been assured by SKL that all German U-boats in the area had been warned to keep well clear of the Pinguin’s track. In which case, this could only be a British boat lying in wait for German blockade runners. Mindful that the Pinguin was currently disguised as the Russian Petschura, Krüder hauled around to the north, hoping to give the impression he was heading for the North Cape and Russian waters. Ignoring the weather, he rang for emergency full speed and the Pinguin, now beam-on to the seas, surged forward, rolling heavily.

Almost immediately the submarine came to the surface again and gave chase, black smoke pouring from her exhausts. She was about 2 miles astern of the Pinguin, wallowing in the heavy seas, which broke clean over her, so that from time to time she almost disappeared from view. An Aldis lamp winked from her conning tower. ‘What ship?’ Pinguin’s yeoman read from the impatient flashes. Krüder, acting out his role as a non-English speaking Russian merchant captain, ignored the signal. A few minutes later the lamp flashed again. ‘Heave to, or we open fire!’

Krüder chose to ignore the order. He had the submarine dead astern, thereby presenting the smallest possible target. Moreover, the enemy’s movements in the sea were so violent as to make her a very poor platform from which to take aim. Pinguin pressed on at full speed and the submarine began to drop astern.

The German captain’s assessment of the situation proved correct when, a few minutes later, three underwater explosions were heard. No torpedo tracks had been seen, but it was certain that the enemy sub had fired a salvo, three torpedoes either hitting the bottom or missing the Pinguin and exploding at the end of their run. And that was that. The submarine held on doggedly for another hour, but she could not match the Pinguin’s speed. She fell further and further astern until she gave up and turned away.

Assuming that the British submarine would have reported sighting a suspect enemy ship, Krüder held a north-easterly course throughout the day, running parallel to the Norwegian coast at a distance of about 70 miles. At 0843 a Heinkel 115 float plane passed low overhead, the same aircraft, or another of the same type, appearing at 2100. Pinguin was being watched over from the air, otherwise she had the sea to herself.