After Caesar had arranged a reconciliation between Cleopatra and the young Ptolemy, he learned from his barber that the eunuch Pothinus and Achillas were devising a plot to assassinate him. Acting quickly, he hosted an elaborate banquet to celebrate the union between brother and sister, and during the festivities, Pothinus was seized by soldiers, dragged outside, and executed. Somehow, Achillas managed to escape and return to his army. Caesar, realizing that war was imminent, and that his few thousand Roman soldiers were hardly enough to withstand an assault from Achillas’s army, sent his friend Mithradates after additional forces in Syria and Asia Minor, hoping, by a rear attack, to defeat the Egyptian army stationed at Pelusium. To ensure the success of his plan, Caesar held not only the young Ptolemy, but also his sister and her tutor Ganamydes as security in the palace. However, his scheme was foiled when Achillas left Pelusium without warning and headed for Alexandria. When his army reached the outskirts of the city, they were greeted enthusiastically by the inhabitants. This news was discouraging for Caesar, who now had to deal with the fanatical mobs of Alexandria as well as Achillas’s army of 20,000 foot soldiers and 2,000 cavalry

Suddenly, Ptolemy’s sister loomed as a heroine to the Alexandrians, something Achillas viewed with displeasure, since his allegiance was with the young Ptolemy. Knowing that Achillas would never bend from this position, Ptolemy’s sister had him executed, then proclaimed Ganamydes general of the Egyptian army and leader of the revolt against Caesar.

The Roman galleys carrying the Thirty-Seventh Legion from Asia Minor had now reached the Egyptian coast, but because of contrary winds, they were unable to proceed toward Alexandria. At anchor in the harbor off Lochias, the Egyptian fleet posed an additional problem for the Roman ships. However, in a surprise attack, Caesar’s soldiers set fire to the Egyptian ships, and the flames, spreading rapidly in the driving wind, consumed most of the dockyard, many structures near the palace, and also several thousand books that were housed in one of the buildings. From this incident, historians mistakingly assumed that the Great Library of Alexandria had been destroyed, but the Library was nowhere near the docks. The Roman historian Lucan reported that Caesar, besieged in the palace, ordered torches to be soaked with pitch and thrown on the Egyptian ships. The fire immediately spread to the rigging and to the decks, which were coated with resin. Devoured by flames, the first of the Egyptian ships began to sink, while the fire spread rapidly toward the rest of the ships. The houses nearest the docks caught fire too; and the flames, driven by gusts of wind, streaked the sky like meteors over the rooftops.

The most immediate damage occurred in the area around the docks, in shipyards, arsenals, and warehouses in which grain and books were stored. Some forty thousand book scrolls were destroyed in the fire. Not at all connected with the Great Library, they were account books and ledgers containing records of Alexandria’s export goods bound for Rome and other cities throughout the world.

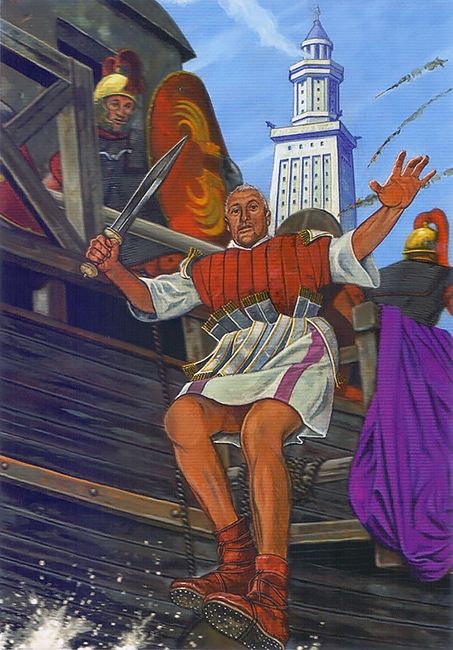

When the sea finally calmed, the Roman galleys appeared off Pharos Island. Caesar was transported there and personally escorted them into the harbor, after which a select force of legionaries under his command set out to capture Pharos. They planned to make one assault from the sea, the other from the eastern harbor, then swing around and take the great promontory Heptastadion. The landing on Pharos was successful and the northern part of the Heptastadion was quickly secured. Caesar himself led the attack to gain the southern section of the promontory that faced the city, but he met with unexpected resistance and soon found himself trapped on the Heptastadion between two attacking Egyptian forces. Several galleys and boats were summoned to his assistance and Caesar got into one of the small boats, but it was so heavy with survivors and wounded it overturned and sank, forcing him to swim two hundred yards to another vessel.

That night, in the company of Cleopatra and several officers, he remained silent during dinner, then withdrew to his bedchamber. Not only had he underestimated the strength of the Egyptian forces, but in the struggle to take the Heptastadion, he had lost a great number of sailors, 400 of his best legionaries, and his favorite purple general’s cloak.

Farther east, Mithridates and his army had already taken the fortress at Pelusium and were advancing down the Nile. The Egyptian force at Memphis was no match for them, and after an easy victory, Mithridates crossed the western bank of the Nile and headed for Alexandria. When the young Ptolemy learned that Mithridates and his army were converging on the city, he took immediate charge of his troops and marched south to battle. Caesar, waiting until the Egyptian army had withdrawn from the city, left a small guard in the palace and sailed eastward, presumably toward Pelusium, but under the cover of darkness, his galleys reversed their direction and sailed quietly back to the western harbor of Alexandria, where he joined forces with Mithridates’ army, and together they headed north to attack the Egyptians, who were still under the assumption that Caesar had sailed away from Alexandria.

The ruse succeeded. In the two-day battle that raged on a fortified hill rising between a marsh on one side and the Nile on the other, the Egyptian army was annihilated. Some survivors tried to escape in small boats across the Nile, the young Ptolemy among them, but as he jumped into one of the crowded boats, it overturned and sank, and he drowned with all the others. His body, later recovered and identified by the golden corselet he wore, was brought to Alexandria and buried with full honors. The following evening, Caesar entered the city in triumph. After five weary months, the Alexandrian War had finally come to an end, and he now was ready to install on the throne of Egypt a queen who would soon bear his child.

A few months later, in early spring, he and Cleopatra boarded a magnificent barge and embarked on a voyage up the Nile. This Ptolemaic state barge was 300 feet long, 45 feet on the beam, and rose 60 feet above the water. It was propelled by many banks of oars, and contained bedchambers, banquet rooms, shrines, grottoes, gardens, and courtyards with porticoes and colonnades. A fleet of galleys and supply ships followed close behind; also several thousand Roman troops as a precaution against any attempt to assassinate the new queen. In all, four hundred ships accompanied the barge as it moved slowly up the Nile. News of this voyage rapidly circulated through the country and crowds of people “came flocking along both sides of the river to view the spectacle, for in their minds, they beheld a gigantic vessel transporting their god Ammon and the goddess Isis through the very heart of Egypt.”

The display of wealth and echo of Egyptian gods and goddesses set the stage for Cleopatra’s reign as queen. Because she presented herself to the Egyptian people as royalty, they would thereafter accord her with near-mystical powers that would protect them and their kingdom.