On the left: Braddock with Washington. On the right: The death of General Braddock

Wednesday, July 9, 1755, dawned hot and clear, a splendid summer’s day with the sunlight peeking over the mountains to the east. Gage and his advance party had marched much earlier, at two o’clock in the morning, in the pitch of the night. Consisting of two Grenadier companies and one hundred other troops, together with two 6-pounders, the advance party marched some five miles in the dark and even before the road had been cleared to the first crossing of the Monongahela, which they passed before dawn. They then continued a further two miles to the second crossing, arriving at eight in the morning. When they approached the river some of the troops thought they saw many French Indians on the other side. Others were unsure. To be on the safe side, Gage ordered the two cannon readied to cover the crossing. The men marched in strict line of battle across the three hundred yards of knee-deep water until they reached the opposite bank, which rose some eight yards from the river in a perpendicular wall. They immediately set to work chopping and sloping it to make a ramp before they could surmount it. Another two hundred yards inland from the bank stood the abandoned house and blacksmith shop of one John Frazer, a Philadelphia German who had set up there in 1742 before the troubles to farm and trade with the Indians. He was possibly the first white settler west of the Allegheny Mountains. Washington and Gist had spent the night there both going and returning on their Rivière aux Boeufs mission in 1753.

Once back on the east side of the Monongahela, Gage posted sentries to secure the camp while the men rested. Those who had any food took breakfast, it being then about nine-thirty. Most had nothing to eat, and some had had nothing the day before. The batman and his master breakfasted on “a little Ham that I had and a Bit of gloster Shire cheese and I milked the Cow and made him a little milk Punch (of) which he drank a little.” Gage dispatched a rider back to Braddock to inform him that he had secured both crossings of the Monongahela without incident and had posted his troops according to the general’s orders.

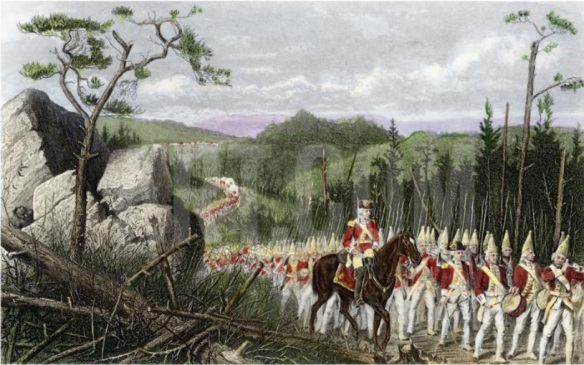

Meanwhile, at daybreak the main army broke camp and began its march. The going was slow, as the troops waited for St. Clair and his pioneers to clear the road. About eight they reached the first crossing, which one British officer described as “extreamly fine having a view of at least 4 Miles up the river.” Braddock, who now assumed more of a personal role in the command, ordered 150 men over in the front, followed by half the guns and limbers, then a further 150 men. Next came the packhorses and cattle, followed by the baggage and remaining guns and limbers and, finally, the rear guard troops who had stood watch on the heights to cover the crossing.

Once over, the general ordered a halt and reformed his units in the proper line of march. Gage’s dispatch rider arrived with his reassuring note after they had advanced just one mile. On reaching the second crossing a further mile to the west at about eleven o’clock, the general saw that the men were still working to clear and widen the slope on the opposite bank to accommodate the heavy howitzers and 12-pounders. He ordered the artillery and baggage drawn up along the beach to wait. The work was completed within about an hour.

Now was the moment of decision. Sitting atop his great bay charger on his leopard skin saddle pad, His Excellency surveyed the scene and with the wave of his hand gave the signal to order the 44th Regiment over first, with the picket of the right. The wagons and packhorses and then the 48th Regiment, with the left pickets which had covered the crossing from the heights, would immediately follow.

The crossing at high noon was the culmination of General Braddock’s career. It was a spectacle, a deliberate statement of the inexorability of British arms. The crossing impressed all who witnessed it, as many who did were later to remark. This was, after all, its intended effect, for Braddock suspected that the enemy was watching. Once the redcoats had assembled, Braddock literally marched the men across the river in formation, with their forty regimental drums beating and their fifes playing the “Grenadiers’ March.” The ripping reverberations of the forty regimental drums, a sound unaccustomed to either Indian or modern American ears, would have resounded through the wilderness for miles and carried down the river valley a good way of the distance to the Forks of the Ohio. The soldiers’ close-shouldered arms stood upright, and their bayonets glistened in the hot July noon sun. The oversized King’s Colour (a Union Jack with the King’s insignia) fluttered at the head of the column. The exhausted horses plunged and clattered across the pebble-strewn riverbed drawing the big naval cannon and shining brass howitzers. Each regiment proclaimed its presence and identity with its regimental flag snapping in the breeze. As Braddock led atop his charger and surveyed the clockwork precision of the crossing, with its tight discipline, splash of color, and time-honored war march, he must have felt pride at the prowess of British military might. Never before had the American wilderness seen such a spectacle.

Once across and reformed on the east side of the river, Braddock and the men let slip a sigh of relief. They figured that if there were any place the enemy would challenge them, it would be on this second crossing of the river. Thinking that all the dangerous passes were behind them, Braddock reined in his advance party and ordered it to march within a few yards of the main body. The army was now within seven miles of Fort Duquesne. The soldiers thought that they might at any moment hear the explosion of the French blowing up the fort in retreat. If not, by that evening or tomorrow at the latest, the army would be encamped before Fort Duquesne and limbering up the cannon that it had so impossibly brought to bear across ocean, mountains, and rivers. For the first time in months there was an air of anticipation and a spring to the soldiers’ step as they moved out.

The landscape through which they marched was sloping, intermittent woodland carpeted with grass and rising to outcroppings of rock at its crest. Water from a spring in the heart of the gentle slope tumbled down to the river. Ancient trees lay fallen along the edge of the forest line, while wild grapevines marked the demarcation line of the plain scoured by the spring floods and the thick-et-tangled upper reaches of the slope. Three concealed ravines, four or five feet deep and eight to ten feet wide, creased the slope. Basking in the early afternoon sun, more than one soldier might have mistaken the hillside for a frontier Elysium.

The army marched only eight hundred yards.

Captain Beaujeu quickened his pace to a run as he heard the “Grenadiers’ March” wafting from the distance. Catching the first far glimpse of the river through the forest, he knew that the English had forded the river and deprived him of the challenge that he planned for the crossing. Fortunately, the three hundred Indians who had split from his force and crossed to the west side of the Monongahela had thought better of their diversion and had rejoined him only minutes before. Spotting the English marching in tight order through the broken grassland before him and the pioneers beginning to attack the tree line with their axes, he took off his three-cornered hat and waved it to his troops, signaling them “Go left!” and “Go right!” The Indians and French instinctively fell into a half-moon formation as they fanned out and took cover behind the trees at hand. Others quickly found the ravines and jumped into their natural protection.

At one o’clock an engineer at the head of the British column thought he saw the fleeting figure of a French officer, stripped to the waist like an Indian but wearing a three-cornered hat and silver gorget, dart between the trees. Gordon, the chief engineer, soon saw what he estimated to be three hundred Indians running through the woods. At the same time the shrill scalping halloo rang out. The English froze in their tracks.

The crash of a volley of fire erupted from nowhere. However, the front lines of the vanguard were out of range, and it had no effect. Nonetheless, the flying column shuddered and came to a halt. Gage ordered the Grenadier companies at the van to fix their bayonets and form in line of battle, with the intention of gaining a hill to the right that was already partially in possession of a party of redcoat pickets scouring the right flank. The Grenadiers quickly followed the first order, but “visible terror and confusion appeared amongst the men,” and they refused to move to the posts Gage assigned them or leave their line of march. However, Gage succeeded in forming them into position in the middle of the road.

“God save the King!” cried a British officer. “Huzzahs” resounded from the ranks as they moved a little further along the road to within musket range of the forest line. Every few steps they executed the classic British formation, kneeling, firing, reloading, kneeling, firing, in ranks according to Bland. The deafening volleys of Brown Bess fire delivered with speed and precision split the wilderness.

On the first volley from the Grenadiers the French Canadian auxiliaries, one half of the non-Indian French forces, turned tail and ran, shouting “Sauve qui peut!” (“Every man for himself!”). On the third volley a lucky shot struck Beaujeu, killing him just minutes into the battle. His second in command, Captain Jean Daniel Dumas, who had been an ardent advocate of the plan to intercept the British, assumed charge…