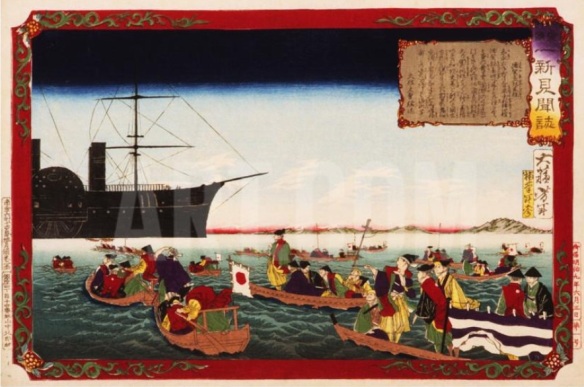

– American Navy Commodore Matthew Perry arrives in Japan, August 7, 1853 –

Woodblock Print

8 July 1853

Japan Opens up to the Modern World

The military and warlike strength of the Japanese had long been to Europe like the ghost in a village churchyard, a bugbear and a terror…Our nation has unclothed the ghost…

An American sailor (1853)

The officer who steered his two frigates and two sailing ships into the fortified harbour of Uraga near Edo (Tokyo) on 8 July 1853 was well versed in naval diplomacy, the realities of war and the advanced technology of his time. Commodore Matthew C. Perry (1794–1858) had commanded the USS Fulton, the American navy’s second steam frigate, and organized the US’s first corps of naval engineers; he had also seen action during the American–Mexican war which had ended with the annexation of the previously Mexican province of Texas. The victory had realized some of the ambitions of American politics’ ‘manifest destiny’ movement which was convinced that the country had a duty to expand – ‘the farther the better’ according to Walt Whitman. But Perry was also a careful strategist who had studied Japan’s two centuries of isolation and concluded that only a show of naval force along with a ‘resolute attitude’ would persuade the Japanese to establish diplomatic and trade relations with the US. Appreciating Japanese veneration for rank, Perry called himself an ‘admiral’ and refused to leave when the representatives of the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan’s hereditary military rulers, told him to go to Nagasaki. This, their only port open to foreigners, was where they allowed a limited trade with the Netherlands. Perry threatened a naval bombardment if he wasn’t allowed to fulfil his mission of delivering a letter from the US president. The Japanese looked at his vessels and decided to let him in. Ever afterwards ‘black ships’ would be their phrase for a western threat.

On 14 July, at Kurihama, Commodore Perry handed Fillmore’s letter to the shogunate’s delegates and told them he would be back for a reply. In February 1854 he returned with four sailing ships and three steamers as well as 1,600 men. The Japanese had prepared a draft treaty of acceptance and, after a face-saving diplomatic standoff, Perry was allowed to land and negotiations began. On 31 March Perry signed the Treaty of Kanagawa which promised ‘permanent’ Japanese–American friendship. Having seen China’s defeat by superior western technology in the Opium War, Japan now wanted to win time while developing her defences. The treaty allowed US ships to obtain fuel and other supplies at two minor Japanese ports, enabled a consulate to be established at Shimoda and paved the way for trading rights. The shogunate had proved incapable of maintaining Japanese isolation. In a characteristic postscript Perry anchored off Taiwan on his return journey and spent ten days investigating the island’s coal deposits with a view to future American mining. Taiwan, he thought, might be a useful base for the US’s future exploration of the region just as Cuba had been for the sixteenth-century Spanish in America. The US government, however, refused his offer to claim American sovereignty. There was, after all, enough Asian adventure to look forward to.

The Japanese response to Perry reflected a power struggle within the Japanese ruling class and the issues raised by his arrival were not new. An unarmed American merchant ship had been fired on in 1837 when it had sailed into Uraga channel; Commander James Biddle commanding two ships – one being a seventy-two-cannon warship – had anchored in Edo Bay in 1846 and been denied trade agreements; Captain James Glynn had sailed into Nagasaki in 1848 and returned to tell Congress that Japan would need a demonstration of force before agreeing to trade negotiations. The Tokugawa shogunate, recognizing that the Perry threat was graver than these earlier forays, received conflicting advice when it consulted the nobility. Many stuck to intransigent isolationism, but Li Naosuke counselled a superficial conciliation which won the day: Japan needed just enough foreign contact to allow her time to build up her strength in order to reimpose isolationism. This approach won and in the next few months Britain, Russia and the Netherlands won their own trade agreements.

This policy divide coincided with a crisis in the succession to the hereditary shogunate since the current holder, Tokugawa Iesada, was childless. Different camps signed up for the competing claims of the shogun’s first cousin, Iemochi, who was still a minor, and those of Tokugawa Yoshinobu, who, although only distantly related to the clan, was the son of the powerful Tokugawa Nariaki. Li Naosuke was among those who promoted Iemochi as heir apparent, calculating that his youth would allow a noble clique to control the shogunate. Nariaki became the chief representative of imperial loyalism within the shogunate and now tried to involve the imperial court in the shogunate’s administration.

By 1858 Naosuke was in a position of real power as tairo or chief adviser to the government and his candidate Iemochi had been chosen as shogun on the death of Iesada. However, his decision to sign a further treaty with the Americans proved to be his undoing. Powerful isolationists had hampered the negotiations and Naosuke calculated that a signed treaty with the US would strengthen Japan’s negotiating position with the British and the French whose squadrons were on the way and whose negotiators would want even more far-reaching agreements. He therefore instructed the negotiators to sign without gaining imperial permission. This provoked the isolationists who, increasingly, saw the emperor as fundamental both to Japanese honour and to their own standing. Armed followers of Nariaki attacked Naosuke in 1860 and beheaded him. In 1862 Yoshinobu, following his father Nariaki’s death two years earlier, became the boy shogun’s guardian. His own succession (1866) to the shogunate, following young Iemochi’s death, proved to be an empty inheritance. The forces of imperial loyalism which had elevated both him and his father – and helped to make him shogun – would turn against the shogunate as an institution, abandon isolationism, and associate the new imperialism with a state-strengthening modernity which took what it needed from western technology.

The Tokugawa shogunate of the 1860s had been destroyed by contradictions. It wanted to strengthen Japan against the foreigners but the only way of doing this was by giving the already rebellious nobility of feudal lords (daimyo) the economic means of self-defence. Such a revived force would inevitably be turned against the Tokugawa. At the same time samurai warriors were pushing their lords to more aggressive isolationism while asserting their own authority through sword warfare. The shogunate had become a prevaricating regime which told its domestic critics that it was opposed to further concessions while at the same time trying to conciliate the great powers with trade agreements.

Power, however, was not just drifting away from the shogun and towards the imperial court. It was, once again in Japanese history, flowing to the provinces. The samurai warriors were dominant in the Choshu region following a successful coup and their forces fired on the foreign shipping in the Shimonoseki Strait. They were then bombarded by western powers and a shogun army forced the province to re-submit to the Tokugawa authority. But the Choshu samurai refused to accept the legitimacy of the submission and a further coup brought to power nobles who had originally been isolationists. Choshu became a centre for discontented samurai from all over Japan.

But Japanese power dynamics were shifting in other directions too. Choshu’s newly dominant daimyo were no longer simple-minded xenophobes; they had studied western military methods in order to reform their military units to dramatic effect. The Shogun army was defeated (1866) when it tried to reassert control in Choshu and in Satsuma – Chosu’s neighbouring province and new ally. Now the daimyo saw how western methods applied in Japanese conditions might help them achieve their goal of a renewal. Yoshinobu lasted just one year as shogun. A group of radical samurai seized the palace in Kyoto and declared an imperial restoration. The military units of Satsuma and Choshu were joined by those of Tosa province to become the new imperial army which marched on Edo and forced it to surrender. The emperor Meiji Tenno, who had succeeded to the imperial throne the previous year (1867), moved into the Tokugawa castle in Edo, which was renamed Tokyo (‘eastern capital’); he presided over the Meiji restoration and its experiment in modernity, wore western clothes and liked western food. But as a prolific poet versed in his country’s literary traditions he also personified the uneasy dynamism of Japan’s experiment in east–west fusion.

A feudal and rural state became an urbanized and bureaucratic one within a generation–a development which had taken centuries in western Europe. The speed of change demonstrated the paradox of embracing emperor worship as a solvent of feudalism, a patriotic duty, a guarantor of unity and a path to modernity. Japan’s ancient religion, Shintoism, was reinvented as an ideology at the expense of Buddhism and supplied a pantheon of national deities. The national education system established by the Imperial Rescript on Education (1890) was western in structure and in much of its content. But Shintoism, as well as Confucianism, was an important element in a curriculum which taught Japanese how to be obedient citizens. The adoption of western techniques in technology, government and business was justified and presented as a way of enabling Japan to work towards the eventual revision (1894) of the unequal trade treaties she had been forced to sign. A telegraph and railway network linked cities and towns while Japan’s seventy-two administrative prefectures replaced the 250 domains of the daimyo. The samurai, who, together with their dependants, numbered some two million, were eventually, after some rebellions, suppressed thereby losing their right to bear swords and sport a distinctive hair-style. A new power – that of the financial cliques (zaibatsu) with close government connections – developed with the government selling industrial plants to chosen private investors. Germany, another country yoking modern capitalism to the remnants of feudalism, provided the parliamentary model which tried to balance the claims of representation with those of imperial control. Japan’s first bi-cameral Diet met in 1890 with the lower house elected on a franchise of 500,000 males chosen on an annual tax threshold of fifteen yen. European-style peerages had been created in 1884 and their holders went into the upper house. The cabinet system, whose members were imperial nominees, was instituted in 1885 and universal conscription strengthened the newly established national army. Japan experienced the pleasure of defeating its ancient enemy China in the Sino-Japanese war, made an alliance with Britain and savoured the first defeat in modern history of a European power by an Asiatic state when it won the Russo-Japanese war in 1904–5. Commodore Perry, by forcing modernity on Japan, had enabled a new sun to rise in the east.