Staff Captain Pyotr Nesterov

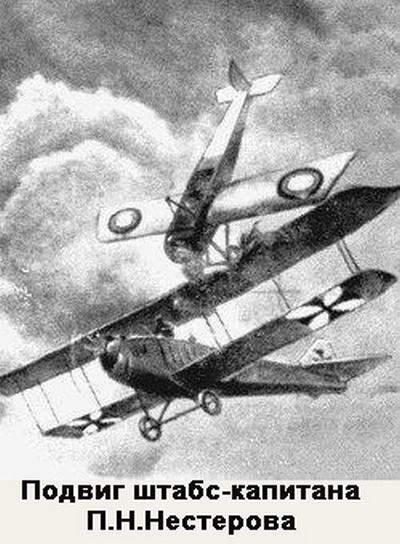

For a country so backward in just about every other branch of technology, it is surprising that Russia had the second largest air force in Europe, after France. The Imperial Russian Air Force – Imperatorskii Voyenno-Vozdushny Flot (IVF), to give it its correct name – was even able to claim the credit for the first enemy aircraft ever destroyed in flight. Piloting a Nieuport IV monoplane, the aerobatic pioneer Staff Captain Pyotr Nesterov was the first man to fly a loop. On 25 August 1914 he repeatedly fired his pistol at an Austrian Albatros BII on a reconnaissance mission, then deliberately flew his Morane-Saulnier Type G monoplane into the Albatros. His specific intent is unknown because, in addition to causing the Austrian aircraft to crash, killing pilot and observer, his own plane was so damaged by the collision that it also crashed, killing him when he fell out on the way down. There were no parachutes at the time, except for observer officers in tethered balloons, because it was thought that this would cause nervous pilots to bail out before they needed to, instead of flying their valuable craft back to base for the necessary repairs.

Formed in 1910, IVF traced its beginnings back to earlier experimental flights by pioneers like Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Igor Sikorsky, who emigrated to the United States in 1919 after the Revolution. Before the war, he built a four-engine airliner named after the Russian folk hero Ilya Murometz, but commonly called ‘the big ’un’, at his Russo-Baltic Wagon Company factory in Riga. Powered by French-built Salmson air-cooled engines, the civilian version had panoramic windows lining the large and comfortable insulated cabin, heated by the exhaust pipes, with wicker armchairs for up to sixteen passengers, a table, bunk, electric lighting – and the first airborne toilet! Hatches on either side of the cabin allowed the flight engineer to scramble out onto the lower wing to service the engines in flight. For the time, it was an extraordinary piece of engineering and set a world record by flying from St Petersburg to Kiev in Ukraine, a return trip of 2,400km, in under twenty-eight hours’ flying time with only one refuelling stop in each direction.

The several military versions designed for service as heavy bombers had a gun position equipped with an 8mm machine gun and a 37mm cannon set in the middle of the upper wing, where the gunner had 180-degree vision at the cost of being completely exposed to the elements. Up to eight other machine guns could be fitted in various positions, including a tail gunner pod, making this an early Flying Fortress. All this armament and the armour-plating that protected the motors made the Ilya Murometz the least favourite target for CP fighters, which also found the powerful prop wash dangerously destabilising if they got too close when attacking from the rear. Navigation instruments were still primitive but did include a drift indicator and simple bombsight. Bomb racks could accommodate up to 800kg of bombs. Seventy-three of these amazing machines were built in all, flying over 400 sorties and leading the way in squadron-strength raids, night bombing, photographic damage assessment and the dropping of safe-conducts to encourage enemy ground troops to desert.

The total of 5,000 aircraft of all types built in Russia between 1914 and the end of hostilities included ‘flying boats’ as float-planes were then called, constructed for the Imperial Russian Navy. Construction of all aircraft was limited by the need to depend heavily on foreign aero engines – mainly from France. Austro-Hungary did not do much better, but Germany allegedly produced over 45,000 aircraft during the war. Spare parts were also a big problem for Russia, given the wide variety of makes and models, for many of which spares were not available locally. Ground crews therefore tried to fit non-standard parts, which caused additional unreliability so that, as the war ground on, many aircraft in front-line squadrons would not have been considered airworthy at any other place or time.

For all the undoubted skills of Russian aircraft constructors and fliers, in the first months of hostilities IVF aircraft were confined to reconnaissance and artillery observation roles because the military applications of flying machines had yet to be fully appreciated. In December 1914 an otryad or squadron of Ilya Murometz aircraft was tasked with bombing missions against both German and Austro-Hungarian armies in the first step towards the carpet bombing of cities forty years later.

Among the other aircraft in IVF was the Anatra DS, built in Artur Anatra’s factory at Odessa in the Ukraine. This was a two-seater reconnaissance biplane with 150hp Salmson Canton-Unne water-cooled radial engine that necessitated an ugly cooling radiator mounted on the centre of the upper wing. The DSS model had radiators mounted on the plywood sides of the fuselage or under the nose. It had a maximum speed of 144kph and ceiling of 4,300m. The pilot had a forward-firing machine gun and the observer used a second machine gun firing in a wide arc. Also made in the Anatra factory was the oddest-looking aircraft of the war. The Anadwa VKh was a twin-boom three-seater biplane light bomber composed of two Anatra D fuselages, of which the left one was occupied by the pilot, and the right by his observer. The machine gunner was seated in a nacelle mounted on the centre of the upper wing, providing excellent all-round vision and field of fire. Powered by twin 9-cylinder air-cooled Gnome rotary engines, it could carry a bomb-load of 600kg at a maximum speed of 140kph and service ceiling of 4,000m.

The Moskva MB 2-bis single-seater fighter was powered by a single Rhône air-cooled rotary engine that gave it a maximum speed of 130kph and ceiling of 3,200m. The single machine gun was not synchronised, on some models firing above the propeller arc. Other models had bullet deflectors on the propeller blades, which seems a bizarre idea today. In 1916 two Russian engineers collaborated to produce the Savelyev Quadruplane. The four wings were in a strut-braced box tilted forward with a Morane-G fuselage fitted between. Under-powered when first flown in April 1916, it went into production with a more powerful Gnome-Monosoupape or Clerget 9-cylinder air-cooled rotary engine, giving it a maximum speed of 132kph and a ceiling somewhere above 2,000m, sufficient for reconnaissance work.

The Voisin-Ivanov was another biplane made in the Anatra factory, primarily for ground attack roles. Fitted with a Salmson P9 water-cooled radial engine, it carried a crew of two with one machine gun and a bomb-load of less than 100kg. Its design was based on the French Voisin LAS pusher biplane, which enabled the observer sitting in the front seat to have a clear field of fire to the front and sides. Maximum speed was 150kph with a ceiling of 3,500m. More than 100 were produced and some continued in use after the Revolution until lack of spares eventually grounded most aircraft in Russia.

At the start of the war, Germany had 200-plus aircraft in a corps designated Die Fliegertruppen, or flying troops. For the first months of hostilities their main activity was reconnaissance, often performed by pilots flying the reliable Rumpler-Taube monoplane which had been in production since 1912 and was instrumental in causing many casualties among Allied troops in Macedonia. As the combat potential of aircraft was realised, in late 1916 the German air force was renamed Die Luftstreitkräfte.

The Fokker MV was an unarmed single-seater monoplane, first produced in 1913. With its single wing above the cabin, it afforded excellent visibility of the ground below and was widely used in early months of hostilities. It was also the platform from which the more successful Fokker EI was developed. Marks II and III were also single-seater fighters, which first appeared on the Russian front in 1915. The EIII had a more powerful engine than the earlier models and one 7.92mm machine gun. At end of 1915 this was superseded by the Mark IV with an up-rated engine and two machine guns. The Mark V, with its Gnome-Lamda 7-cylinder rotary engine had a tubular metal construction that made it light and strong. Some modified Mark VIII models were designated AI and AIII, and fitted with a single 7.92mm parabellum machine gun. The Fokker DV1 was an all-metal biplane with a speed of 200kph that could reach a ceiling of 6,000m. However, it only arrived on the Russian fronts in April 1918, at the time of the Armistice.

The Albatros DIII biplane was feared by Russian pilots as the most dangerous German aircraft of the war, with its speed of 165kph and a ceiling of 5,000m. Its successor the Albatros DV biplane was reputed to be able to out-fly most Allied aircraft with the exception of the Bleriot-SPAD 7. The Roland CII appeared on the Russian fronts early in 1916, and was used for local and long-range recce, correction of artillery fire and precision bombing until mid-1917. The Fokker Dreidecker triplane was inspired by the British-built Sopwith triplane. With the fuselage between the two lower wings, early models had structural problems but the Mark V and later models stood every test on the Russian fronts starting in February 1917. Because of its inherent instability, the aircraft was loved by fighter aces for its ability to take immediate evading action and was the machine of choice for the German ace Manfred von Richtofen. It was in one of these that he was shot down and killed in April 1918.

The AEG GIII was the first German long-distance bomber – and range was imperative on the widespread Russian fronts. It was produced from mid-1915 onwards and was in service from the end of that year. It had two machine guns and could carry a 300kg bomb-load. The Zeppelin-Staaken RVI was another long-distance heavy bomber. Armed with four machine guns, it could carry eighteen 100kg bombs. The four powerful Maybach engines were mounted in two pods on either side of the fuselage that each had one pusher and one puller propeller. Between the two motors in each pod was a space for the flight mechanic to sit when carrying out in-flight maintenance. Although built in Germany, the Hansa-Brandenburg C1 biplane was passed on to Austro-Hungarian fliers as being not quite good enough for use as a fighter, although adequate for reconnaissance roles. Surprisingly, twelve Austro-Hungarian airmen scored sufficient kills with it to be labelled aces.

Although a side-show to the main conflict on land, the Baltic was itself a theatre of war. Here, Russia was at a great disadvantage because, during the Russo-Japanese war, Admiral Zinovi Rozhdestvensky had led the Russian Baltic Fleet from the Latvian port of Libau (modern Liepaja) to relieve the blockade of Port Arthur by the Japanese – a task well beyond the capacity of the Russian Pacific Fleet. On 14 May 1905 this fleet belatedly set course from Vietnam’s Cam Ranh Bay for the surviving Russian naval base at Vladivostok, Port Arthur having already surrendered during the long voyage. Admiral Togo Heihachiro’s more modern and better armed warships were waiting in ambush in the Tsushima Strait between Japan and Korea. In the long and bloody Battle of Tsushima 27–29 May the Russian fleet lost over 200,000 tons of shipping, against Heihachiro’s losses of 300 tons. Casualties were similarly disparate, with 4,830 Russian sailors killed and 6,000 taken prisoner, including the admiral, while Japanese casualties totalled less than 200.

Nine years later, with the Russian Baltic Fleet still well below strength, by 26 August 1914 both German and Russian submersibles patrolled the Baltic. In October 1914 a German submersible sank the Russian cruiser Palladia in October 1914 and a Royal Navy submarine sank the German heavy cruiser Adalbert. When the German cruiser Magdeburg went aground while mine-laying off the Gulf of Riga, its crew was evacuated by an escorting destroyer but left behind their code books, which greatly helped to break encrypted German radio traffic when forwarded to the British Admiralty. In the Baltic both sides laid thousands of mines, claiming several ships, and also shelled coastal towns held by the enemy.

In late August and early September 1914 Polish-born IVF pilot Jan Nagórski was the first man to fly over the Arctic, making five search missions in his Farman MFII biplane in the hope of finding the lost Russian polar explorer Georgi Sedov. It was an incredibly brave undertaking, given the state of low-temperature engineering knowledge and the fact that the only lubricant was castor oil. Nagórski’s subsequent war service included flying as eyes-in-the-sky for the Baltic Fleet from a base at Turku, Finland, where he was the first man to loop the loop in a float-plane, in September 1916. In 1917 his aircraft was damaged far out over the Baltic and Nagórski declared missing in action when he did not return to base. After several hours in very cold water, he was picked up by a Russian submarine and recovered from exposure in a military hospital in Riga. Because the report of his rescue and recovery never reached his HQ, he was declared dead – and stayed that way for thirty-eight years! In 1955 he attended a lecture in Warsaw where he was referred to as ‘a dead Russian aviator’ and announced to the amazed audience that he was neither Russian nor dead.

On 8 August 1915 the largely obsolete Russian Baltic Fleet of five pre-dreadnoughts with four dreadnoughts, six ancient armoured cruisers, four light cruisers, destroyers, torpedo boats and a few small submarines – including three Royal Navy submersibles that had sneaked into the Baltic – found itself facing a strong German naval task force of eight dreadnoughts, three battle cruisers, some light cruisers and destroyers of the High Sea Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Franz Ritter von Hipper. Hipper was attempting to break into the Gulf of Riga to destroy Russian naval forces based there and lay mines to interdict Russian use of the port of Riga – a strategically important communications hub. The Germans’ first problem was negotiating the Russian minefields in the Irben Strait, which proved costly. After two minesweepers were sunk, the first attack was abandoned.

On 16 August a third minesweeper was lost but, more importantly, the ageing Russian battleship Slava was driven off by two German dreadnoughts while the main force stayed out in the Baltic. That night, two German destroyers broke through the Irben Strait, hunting the Slava. Battle was joined by Russian destroyers and one German destroyer was so damaged that it had to be scuttled. After daybreak, German dreadnoughts Posen and Nassau pursued Slava and scored three hits before it withdrew to the shelter of Moon Sound. After further mine-clearing, the first German warships were able to penetrate the Gulf of Riga and attack Russian shipping there. A blow for Britain was then struck when RN submersible E-1, captained by Lt Commander Laurence, scored a torpedo hit on the battle cruiser Moltke, damaging it in the bows.

On 14 August the British Admiralty had ordered Lt Commander Layton’s E-13 and four other submersibles to sail from Harwich to reinforce the Baltic flotilla, but E-13 was not a ‘lucky ship’ and ran aground on the Danish island of Saltholm while negotiating the narrows of Øresund on the night of 18 August. In spite of Danish navy attempts to screen it, two German torpedo boats opened fire on the stranded vessel. Re-floated, E-13 was interned until the end of the war, when it was returned to Britain, its captain having meanwhile been allowed to escape and find his way home. Sister ships E-18 and E-19 arrived safely in the port of Riga the following month. The fate of the fourth British submarine is a mystery.

After the damage to Moltke, Hipper decided to break off contact in what was really a ground support operation, reasoning that the High Seas Fleet would have need of its capital ships for more important naval tasks ahead. On land, for most of the Russian troops food was poor or non-existent for days on end; there was no home leave; due to lack of medical facilities, a small wound often meant death from infection. But the main problem lay in the inability of the Russian munitions industry to supply guns and especially shells for the artillery. Because of the lack of rifles to issue to them, the proposed call-up of the 1916 class had to be postponed. But there were signs of change. Some Japanese materiel was arriving from Vladivostok via the Trans-Siberian railway.

Lying on a mile-wide stretch of the estuary of the Northern Dvina, Archangel was not much of a harbour in European terms. This river was not a northern stretch of the Baltic Dvina, but a separate watercourse, the word dvina being apparently a pre-Russian word for river. Although devoid of wagon-ways along which ponies could haul freight, and lacking cranes, Archangel was an established town overlooking the water, over a mile wide at this point. The chaos here, caused by the impossibility of moving the stores away fast enough, made a negative impression on every visitor. The nearest railhead was across the river at Bakaritsa, to which freight had to be transported by barge or, in winter, hauled across the ice of the frozen river by pony-drawn sled for onward transportation along the ramshackle narrow-gauge railway leading to the south. In 1914 the railway had a capacity of twelve short trains a day; the requirement was for at least five times this level of traffic. An additional, seasonal problem was that the Bakaritsa terminal was flooded during the spring thaw, when freight transported across the estuary by barge was then hauled through mud and water 8 miles further south, to Isakagorka.

Given the vital necessity to import materiel for the Russian war effort, one would have thought that Nicholas II’s government would have put in hand a priority programme of modernisation of the port, its freight handling facilities and the totally inadequate railway to the south. There was no such programme. Money was made available as and when: 1.5 million roubles to purchase two Canadian ice-breakers; 270,000 roubles to purchase metal barges to replace the rotten old wooden ones; another 20 million roubles for the widening of the railtracks – and so on. It was a Russian problem. No one was in overall charge, yet somehow by the spring of 1916 supplies were flowing in something like satisfactory manner.

To get around the insoluble problem of Archangel being ice-bound for half the year, a contract was given to a British company for the construction of a railway reaching all the way from Petrograd to the ice-free fishing port of Aleksandrovsk (now Murmansk) on the Kola Peninsula. It lay 350 miles to the north-west of Archangel, but was ice-free all year, thanks to the mitigating effects of the Gulf Stream. This warm-water inlet was to become the home port for the Soviet Cold War nuclear submarine fleet. The British company backed out – either because of the nature of the near-impossible job or because of the difficulty of dealing with the Russian authorities. A larger than life character named Admiral Roshchakovsky – big, bluff and with a chestful of medals – was given thousands of German and Austro-Hungarian POWs as forced labour to build a single-track railway from the fishing port of Aleksandrovsk to connect it with Petrograd and points south. As when Stalin ordered the construction of the White Sea Canal across the same region using Gulag labour in 1931–33 at the cost of 35,000 lives, so thousands of these POWs died during construction of the line.

There being no commercial docking facilities at Aleksandrovsk, Roshchakovsky’s labour force built a port too – not that any westerner was other than depressed at the first sight of the unplanned sprawl of hastily built wooden shacks that was to be their home there. While the 600-mile railway was a-building, Roshchakovsky requisitioned thousands of Lapps and their reindeer to haul sledges laden with stores south towards the fronts. The Lapps had formally been exempted from this sort of exploitation and had to be threatened with the execution of their hereditary leaders before they gave in. It was at Aleksandrovsk that the Royal Navy based a flotilla of armed trawlers for minesweeping the shipping lanes around the northern tip of Norway. In 1916 a permanent town named Romanov na Murmane was founded, and later became modern Murmansk.

Aside from the appalling winter weather, there can be few more difficult terrains through which to drive a railway across the permafrost tundra, of which the top half-metre gradually thawed in summer to destabilise the rails and release swarms of vicious mosquitoes that tormented the labourers. In anticipation of its completion allowing freight to travel directly to Petrograd, the Royal Navy was sweeping German mines from the sea lanes to the north Russian ports – although, as Knox himself was to discover, not always successfully.