On the Don Front, the going was more difficult. Batov threw his 65th Army at General Alexander Freiherr Edler von Daniels’s 376th Infantry Division, but his infantry made little progress against a determined German defense. Batov found easier going at the junction of the 376th and the 1st Romanian Cavalry Division, and the Soviets were able to advance as they pushed the Romanians aside. Von Daniels was forced to arc his left flank to prevent the Russians from breaking into his rear as a result of the Romanian cavalry’s retreat.

In Stalingrad, Paulus was informed of the Soviet attack at 9:45 AM, but he seemed relatively unconcerned. The German general ordered Heim’s XLVIII Panzer Corps to advance toward Kletskaya to support the Romanians and then went back to briefings concerning the fight for the city. Heim put his units on the road and headed toward his objective, but at 11:30 new orders arrived, this time from Hitler’s headquarters. The feisty panzer general cursed roundly as he read the message ordering him to turn his forces northwest to the Bolshoy area and stop Romanenko’s armored units. Valuable time and fuel were lost as he reformed his attack force.

Meanwhile, Paulus began receiving more reports concerning the Russian attack. The first fragmented information had caused little alarm. After all, they were coming from Romanians, and everyone knew that they tended to exaggerate and were prone to unnecessary panic.

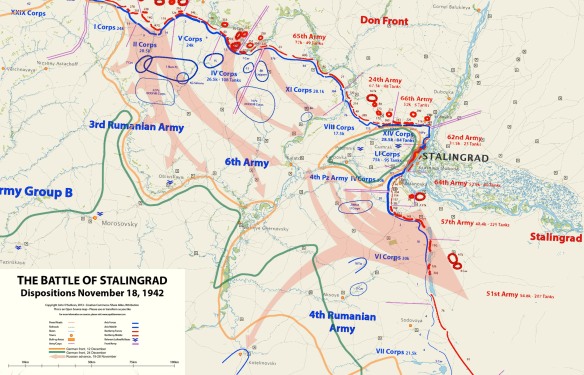

Toward noon, the situation became clearer. This time the staff officers of the 6th Army definitely took notice. A Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft reported hundreds of Soviet tanks advancing across the steppes northwest of Stalingrad. Clear reports from German liaison officers flatly stated that the 9th, 13th, and 14th Romanian Infantry Divisions had been shattered and were no longer capable of any organized resistance.

Although Paulus had three panzer divisions (14th, 16th, and 24th) and three motorized divisions (3rd, 29th, and 60th) at his disposal, he did nothing to form a strike force to stop the Soviet armor. Preferring to keep them engaged in and around Stalingrad-a pure waste of armor in an urban battle-he relied on Heim’s panzer corps to deal with the Russian attack.

A German panzer corps in 1942 was a formidable weapon that could take on a Soviet Tank Army and usually come out on top. Heim’s corps, however, was a panzer corps in name only, something that seemed to slip by the generals that were expecting him to stop the Russians.

By the time Heim was ordered to attack, his 22nd Panzer Division had only about 30 combat-ready tanks. His motorized elements were critically short of fuel, and the orders changing the direction of his attack only made the problem worse.

Heim’s mechanized units were also plagued by the forces of nature. While bivouacked, mice had gotten into the tanks and armored personnel carriers and had gnawed on or through some of the electrical wires in the vehicles, causing them to break down as the systems shorted out. Another problem was the width of his tank treads. The Russian T-34 had a wide, gripping track while German tanks had narrow tracks, causing them to slip and slide on the icy terrain. Nevertheless, Heim and his men pushed forward, hoping to surprise the Russian spearhead.

The weather worsened during the afternoon of the 19th, with the freezing mist lowering visibility to almost zero, and maps were practically useless as the Soviets continued their drive. Taking into account the possibility of bad weather, Russian commanders had enlisted area peasants as guides, but even they were having a difficult time traversing the mist-shrouded landscape.

It started getting dark before 4:00 PM, which only added to the difficulties faced by the Russian tank crews as they pushed toward their objectives. To make things worse, the wind picked up and snow began falling, which led to almost blizzard-like conditions on the steppes.

Having essentially obliterated the Romanian defenses, the Soviet tank commanders felt reasonably assured that their only threat would come from a possible German counterattack. All things considered, that attack would probably be directed against Kravchenko’s 4th Tank Corps, as that unit was advancing closest to the main 6th Army forces at Stalingrad.

It would have worked that way if Heim had not received new orders sending him toward Bolshoy. Heim’s panzers, now numbering about 20, hit Butkov’s 1st Tank Corps near the Chir River at Pestchany. It was an uneven battle from the start, with the Germans being outnumbered, outgunned, and outmaneuvered. In an almost suicidal action, an armored group led by Oberst (Colonel) Hermann von Oppeln-Bronikowski tore into the Russians. Supported by the 22nd Panzer’s antitank battalion, von Oppeln’s tanks managed to isolate and destroy several Soviet tanks in Butkov’s spearhead.

The Soviets regrouped, and the unequal struggle continued into the night until Heim ordered the battle to be broken off. He told his commanders to make for the Chir River crossings and get to the west bank of the river, thus saving his panzer corps from encirclement and annihilation. Those retreating units would remain a thorn in the side of the Russians for days to come.

The retreat order had the expected consequences for Heim as a furious Hitler recalled him to Berlin, stripped him of his rank, and had him imprisoned. He was released 10 months later without having been tried. On August 1, 1944, his rank was restored, and he was appointed commander of Fortress Boulogne on the Western Front.

At Heeresgruppe B headquarters, Generaloberst Baron von Weichs recognized the danger he faced earlier than most. He issued directives at 10:00 PM on the night of November 19 to try and forestall the looming disaster.

“The situation developing on the front of the 3rd Romanian Army dictates radical measures in order to disengage forces quickly to screen the flanks of 6th Army,” he wrote.

Among those measures was ordering all offensive operations in Stalingrad to cease. He also directed Paulus to detach two motorized formations, an infantry division, and all anti-tank units he could spare to stop the assault forces of Vatutin and Rokossovsky. These measures may have blunted the Soviet advance, but it was already too late. On November 20, the second stage of Uranus began as Eremenko’s southern anvil began moving to meet the northern hammer.

The same bad weather plaguing the northern Soviet forces also hampered the Russians in the south. Icy fog made the going slow as the assault forces of the Stalingrad Front edged closer to Constantinescu’s 4th Romanian Army. At 10 AM, the Russian artillery opened up along the front. Soon after, the initial assault troops were already pouring through the Romanian line.

German soldiers in the 297th Infantry Division, adjacent to the 20th Romanian Infantry Division, watched in awe as the human flood of Russians advanced. As on the northern sector, some of the Romanians fled or surrendered almost immediately, while others fought bravely until being overwhelmed. Reports came in speaking of Romanian antitank crews firing their pitiful 37mm guns until they were crushed beneath the marauding Soviet tanks of the initial attack forces.

The leading Russian armored and mechanized forces performed well, but command and control problems, the bad weather, and problems getting across the Volga River crossing points delayed the spearhead units designated to exploit the breakthrough. Maj. Gen. V. T. Volsky’s 4th Mechanized Corps, designated to advance with Maj. Gen. N. I. Trufanov’s 51st Army, was supposed to strike between Lakes Sarpa and Tsatsa, but its units had not yet concentrated. The same could be said for Colonel T. I. Tanaschishin’s 13th Mechanized Corps.

Angry messages flew back and forth as the delay continued. The spearhead units were supposed to attack at 10 AM, but it was already well after noon, and there was still no sign of movement from the corps. General Markian M. Popov, the deputy commander of the Stalingrad Front, headed to Volsky’s headquarters and confronted him directly.

The angry exchange between the two lasted for some time before Volsky finally gave in and ordered his still disorganized units forward. Tanaschishin was also ordered forward immediately. It was already past 4 PM, and the Soviet timetable was hours behind schedule. As they moved out, Volsky’s units became intermixed, causing further confusion as they headed westward.

The Germans reacted much more quickly to the southern attack than they had on the previous day. General Hans-Georg Leyser’s 29th Panzergrenadier Division, nicknamed the Falcon Division, was ordered to hit the flank of Tanaschishin’s 13th Mechanized Corps. The 29th was a first-rate division, and its troops moved out quickly to meet the foe.

About 10 miles south of Beketovka, Leyser’s armored columns slammed into elements of Tanaschishin’s corps. The panzers bloodied the Russian tanks and sent the mechanized units reeling, causing the Soviets to beat a hasty retreat. It was a shining moment in an otherwise dismal day for the Germans, but the victory was short lived.

Farther west, the Soviets were running rampant through the retreating Romanians. Leyser was ordered to turn his division around to protect the exposed southern flank of the 6th Army, leaving the field to Tanaschishin’s forces, which were regrouping for a counterattack.

While the fighting raged south of Stalingrad, the northern sector reeled under hammer blows from the South West and Don Fronts. General Strecker’s IX Army Corps, its left flank left hanging by Dumitrescu’s retreat, was forced to form an arc to meet the advancing Russians. General von Daniels’s 376th shifted its front westward to meet the 3rd Guards Cavalry Corps, while General Heinrich-Anton Deboi’s 44th Infantry Division, forced to leave much of its heavy equipment in place because of lack of fuel, extended its line to cover the gap left by von Daniels’s shift.

Meanwhile, Kravchenko’s 4th Tank Corps turned toward the southeast. Its objective was the Don River town of Golubinski, which happened to be Paulus’s headquarters. At the same time, units of the 5th Tank Army continued to smash isolated pockets of Romanians that tried to stand and fight.