Color photograph of U.S. Army DUKW amphibious trucks on the beach at Anzio, Italy during Operation Shingle, April 1944. (Official U.S. Navy Photograph.)

As the first refugees were being evacuated from Anzio, Generals Alexander and Clark, together with a host of other high-ranking officers, were arriving. The two men had received a positive report from Lucas at 0300 hours that the landing had been successful and good progress was being made. Thus, as soon as it was light, the party from Caserta made their way to Naples harbour and were taken by fast PT boats to visit VI Corps. The news en route continued to be heartening with Gruenther staying in close contact with Clark who was encouraged that no German armour had yet been encountered. The flotilla arrived at the Biscayne at 0900 hours, and after a detailed situation report from Lucas, the group ventured onto the beachhead. Alexander visited 1st Division and spent considerable time with 24th Guards Brigade. Lieutenant William Dugdale, commander of a Grenadier Guards Anti Tank platoon, was one of the first to encounter Alexander whilst on the beach having dealt with some local difficulties:

The naval Lieutenant who commanded our Landing Ship hit a sandbank about 200 yards off the beach and we came to a shuddering stop. The Carrier Platoon roared off and disappeared beneath the waves but by their snorkel tubes they survived by dint of much revving of the engines the carriers all got ashore. The Anti-tank Platoon was less lucky and two of the six tugs sank and stopped in the water with their guns behind. After two hours of hauling and heaving we finally got a tow line on them and pulled them through the surf. I emerged from the water soaking and cross to be confronted by an immaculate General Alexander in field boots who said, ‘You look extremely scruffy’ to which the only answer was ‘Sir’ and a salute.

Dressed in his trademark fur-lined jacket, riding breeches and peaked officer’s cap, the dapper, imperturbable Harold Alexander was instantly recognisable. A group of guardsmen were impressed that the general did not break his stride when a salvo of exploding 88-mm shells showered him with soil. ‘He brushed off the soil like he would the drops of water having been caught in a shower of rain’, one said, ‘and continued on his way chatting to his aide who looked as though he’d seen a ghost.’ Like Clark, Alexander did not lack physical courage and had been wounded and twice decorated for leadership and gallantry during the First World War. He thought that it was important to show the troops not only that he was willing to share their danger, but that it was important to be calm under pressure. His companion, Admiral Troubridge, was not afraid to show his concerns however, and as he pulled himself up from a nearby ditch was heard to complain: ‘I don’t feel safe except at sea. This is most unfair, as really I am a non-combatant on land.’ Whether the General’s tour was a boost to the troops’ morale or merely distracted them from their duties is a moot point, but it was certainly remembered. The Scots Guards official historian writes: ‘General Alexander made a tour of the beach-head that morning, wearing his red hat and riding in a jeep followed by his usual retinue. We were again reminded of the likeness of the operation to an exercise – the Chief Umpire visiting forward positions and finding things to his satisfaction.’ He seems to have found ‘satisfaction’ in most of what he saw that morning and Clark felt the same. Meeting Truscott at the 3rd Division command post, the two men discussed events over a breakfast of eggs, bacon, and toast prepared over an open fire by Private Hong. No sooner had they finished than Lucas and his Chief of Staff arrived and Hong had to start cooking again. Throughout the morning a succession of visitors enjoyed breakfast, but left Hong fuming ‘Goddam, General’s fresh eggs all gone to hell.’ Clark visited Lucas again before he left for Naples that afternoon and praised what had been achieved so far, but also offered the advice: ‘Don’t stick your neck out, Johnny. I did at Salerno and got into trouble.’

VI Corps had made a solid start, but even in the earliest hours it was conservative. Whilst there was ample opportunity for Lucas to push out further and faster, his innate protective mentality allowed the Germans to establish strong defensive foundations. Although the enemy were about as weak as anybody could have anticipated for much of 22 January, and in spite of the fact that VI Corps headquarters understood that the enemy would only get stronger, Lucas remained focused on fulfilling Clark’s primary aim of a secure beachhead in a methodical and workmanlike manner. Even if it was imprudent to strike out for the Alban Hills at this stage, Lucas seemed blind to the possibility of taking as much important ground as possible in order to create a launch pad for offensive action and to provide defensive anchors. There seemed to be a lack of urgency about the advance when with a little more derring-do, VI Corps could have threatened Aprilia and Cisterna. Penney in particular felt that a wonderful chance was being wasted and his respect for Lucas rapidly diminished from that moment on. In the Padiglione Woods the Guards Brigade waited for orders, but none came. They built fires, ate their stale rations, drank tea and smoked as new German arrivals seeped into defensive positions on more advantageous ground. As Vaughan-Thomas wrote of that day, We held the whole world in our hands on that clear morning of January 1944.’ But John Lucas was not the only General to reveal a lack of boldness at Anzio. Another was on his way from Verona.

Eberhard von Mackensen

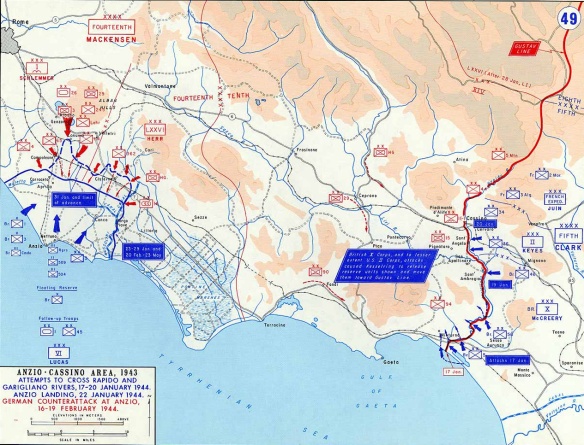

Eberhard von Mackensen grumbled throughout his flight from Verona that ‘a withdrawal of Tenth Army was the only way to save the German army in Italy.’ Arriving with the Fourteenth Army headquarters advance party to take possession of a nondescript building at the heart of German-occupied Rome, the General lost his temper at the mess that had been left by its previous occupants. Von Mackensen was a deep-thinking officer, highly professional and capable, but he had a superficial side to his nature. As German forces in Italy frantically sought to respond to the gauntlet thrown down at Anzio, this austere Prussian aristocrat, whose father had been Field Marshal during the First World War, announced that he would not move into the building until it had been tidied. While cleaners swept he and the vanguard of his staff took over a local café that had just one telephone but – this being Italy – three coffee makers. Kesselring, who disliked von Mackensen’s attitude and pessimism, had given his subordinate clear orders: ‘set up a temporary headquarters in Rome, and as soon as you are ready move to the Alban Hills and establish a permanent base . . . Prepare a plan to pin the Allies in their bridgehead with a view to a counter-attack as soon as was possible.’ As his staff climbed the stairs to the newly dusted second floor ‘Map Room’ that afternoon, they were greeted by the sound of a dozen ringing telephones. Satisfied that his office was the largest and with the best view, von Mackensen got to work. As Mackensen played the prima donna, an ever-growing number of German troops were being conveyed towards the beachhead. Many did not know where they were going, why and what they would find at their destination. One officer being thrown about in the back of an aged Renault truck that afternoon was Rittmeister Edwin Wentz, the commander of a replacement company in the Hermann Goring Panzer Division. At the time of the Allied attack the fifty-year-old had been sitting in the company kitchen drinking ersatz coffee. The bitter weather had aggravated an old shoulder wound that Wentz had picked up in 1916 on the Somme, and the intense pain had woken him early that morning. As he sat rubbing the scar where the shell fragment had entered his body all those years ago, he reminded himself that battles were a young man’s game. Wentz was happy enough to provide a finishing school for young infanteers before they went into the line, but he didn’t want to fight any more. Just as he was pouring himself another coffee, a clerk burst in and breathlessly reported that a Major was on the telephone. Curtly informed about the Allied landings, Wentz received his orders: ‘You must take your company and move them towards the Anzio beachhead. You will receive further instruction later.’ He could not believe what he was hearing—his men were keen but had only the most basic military skills. But Wentz’s men were not representative of the wider Hermann Goring Panzer Division which, commanded by Generalleutnant Paul Conrath, had been hardened by its experiences in Sicily and the Gustav Line.

Everything had been loaded in under forty-five minutes and one hour later, just after noon, they left having been told to get to the battlefield before dusk, giving enough light to reconnoitre the positions they were to take up. However, Edwin Wentz worried about movement in broad daylight due to enemy aircraft. Clattering around in the back of the trucks that afternoon, these men were dazed by the speed of events. The wooden seats provided little comfort, and the soft-skinned vehicles scant shelter from the icy weather, but some managed to sleep, their heads lolling over their colleagues who tended to ignore them. Most just sat back, quietly smoking or bent forward over their packs staring out at the frozen countryside, lost in their own thoughts. There was little talk, although the inexperienced were prone to give a running commentary about the position and progress of the convoy. The veterans tended to keep their own counsel until provoked. One sergeant, who had seen action at Stalingrad, recalls: ‘The youngsters were like little children going on an adventure, excited and apprehensive in equal measure and prone to asking every fifteen minutes, “Are we there yet?” God, they were annoying, but like parents we had to remain patient and try and take their minds off the present by talking about other things. I tried not to get too close to them. Experience told me that once in battle their chances of surviving for more than a couple of days in action were extremely limited.’ At one point they were subject to a fleeting air attack and the drivers sped up and pulled off the road. ‘Dismounting, the men took cover and fired on the aircraft with machine guns and rifles. It made one run strafing the road and then departed. After that, it became quieter and we reached the objective without further incident.’ Alighting at Cisterna, the company found some units of the division had already arrived and were digging in, whilst others were being deployed further forwards. A Panzerjäger Battalion from 1st Regiment armed with towed 7.5-cm Paks, for example, was moving closer to the front line. By the time that Wentz and his men had received their orders, this battalion was fighting an American patrol which advanced to Isola Bella, just two miles south of Cisterna. Lieutenant Ernest Hermann recalls:

The 1st Platoon opened fire and stopped that movement. The enemy pulled back to Borgo Montello and the 1st Platoon pushed on close behind him as ordered. It advanced to just before Borgo Montello. The enemy had dug into the town and opened fire with machine guns, small arms, antitank guns and tanks, making a further advance unthinkable … The platoon found the best positions available and went over to the defence.

As soon as the Allied guns were able, they targeted the enemy as it endeavoured to organise its defences in the open, but the Germans returned fire just as soon as they were able. And so began the first of the deadly artillery duels which were to characterise the Battle of Anzio.

As Cisterna was occupied, Kampfgruppe Gericke was being strengthened on the other side of the beachhead by the arrival of Battalion Kleye. With the ability to hold more ground with two battalions, Kleye was sent to defend Ardea, whilst Hauber was to concentrate on the Via Anziate. Joachim Liebschner, an eighteen-year-old Lance-Corporal from Silesia, says that the road attracted fire from the outset:

I was a runner which meant that I had to try and keep communication between my own company and battalion headquarters. We were issued with a bicycle and it was really a great big joke because when we moved forward, the harder the artillery fire became and we were then attacked by aeroplanes. When everybody jumped into ditches to the left and right I was left with the bicycle. Eventually I went to the Sergeant Major and said look when am I going to use my bicycle here, and he said ‘You signed for it, you’re responsible for it!’ typical German kind of answer to a question … I left it against a tree and thought I could find the tree again when we get to the front line. Not only had the bicycle gone but the tree had gone as well. The artillery fire in this sector, people were saying, was of comparable strength to that in the 14-18 war.

The shells crept ever nearer, tearing up the ground with a blast of such intensity that its sound waves were soaked up by the chests of the paratroopers. But it was not the men new to battle that struggled most with the bombardment; it was the veterans and, as Liebschner says, one sergeant in particular who had been wounded and traumatised on the Eastern Front:

He lost his nerve altogether. Most of us didn’t know what we were letting ourselves in for, but this fellow had been in the front line several times and the closer we got, the more he started shivering and complaining of a headache and sickness and his legs were giving out. He couldn’t move. We left him underneath a small bridge shivering and crying and he was hysterical. I never heard of him again.

That evening a strong patrol from Battalion Hauber was sent down to Aprilia. As it was such a vital town that had not defended all day, Gericke expected to hear that it was occupied. To his amazement he learned at 2030 hours that it was not and passed the information on to the recently arrived Lieutenant General Fritz-Hubert Gräser. Gräser was the commander of a 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division kampfgruppe which had been ordered to take over the defence of the Via Anziate from 4th Parachute Division thus allowing Gericke to concentrate his forces on the west side of the road. The critical road in the beachhead was to be defended by a more experienced division. Although Gräser’s force also contained some replacements, 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division was of more varied stock for, at its heart, were veterans of the Eastern Front, with a proportion having served at Stalingrad where the original division had been all but wiped out. The division had fought well at Salerno and was reaching the peak of effectiveness. Gräser immediately occupied Aprilia.

By the time that the panzer grenadiers were preparing the buildings of Aprilia for defence, Schlemm had established his I Parachute Corps headquarters in the Alban Hills and was in full command of the German forces at Anzio. Kesselring was furious with his predecessor’s efforts that day. Although the untalented Schlemmer was obviously out of his depth in such an operation, his inability to carry out simple orders was inexcusable. Monte Soratte had instructed Schlemmer ‘to push all units as they arrived as far south as possible so as to help the flak slow down or halt the enemy advance’, but instead he formed a strong ambushing force in the Alban Hills in case of a push on Rome. The 20,000 men that had made it through to the beachhead were either surplus to his requirements, had slipped through his net, or had ignored his orders. Through the incompetence of one man in a position of power, the Germans’ carefully laid plans could have failed. Had the Allies chosen to advance swiftly soon after their landing, they would at the very least have been able to seize valuable ground for an expansive beachhead. As Kesselring later wrote:

Every yard was important to me. My order, as I found out on the spot in the afternoon, had been incomprehensibly and arbitrarily altered, which upset my plan for immediate counter-attacks. Yet as I traversed the front I had the confident feeling that the Allies had missed a uniquely favourable chance of capturing Rome and of opening the door on the Garigliano front. I was certain that time was our ally.

As was the Field Marshal’s style, on the day of the invasion he had been decisive in his actions and visited the front personally. Far from doing what the Allies had wanted him to do and withdraw in a panic from the Gustav Line, Kesselring had remained unfazed by Operation Shingle. Anything else would have been distinctly out of character. In spite of von Vietinghoff’s whinging that with so many troops having been taken from him he could not hold his front, and advocating an immediate withdrawal, Kesselring literally and metaphorically held his ground. There was no need to withdraw and in any case, as he told von Senger und Etterlin ‘the present line is shorter and therefore more economical, than a line running directly in front of the gates of Rome straight across Italy.’ Kesselring was not minded to act as the Allies wanted him to and was determined to regain the initiative. First he would build up a critical mass of troops, and then he would push the Allies back into the sea. The American historian Carlo D’Este has written: ‘Kesselring symbolised the German defense of Italy, and he became the bedrock upon which it was built. Where others would have drawn the wrong conclusions and overreacted, Kesselring remained composed and was quite literally the glue that held the German Army in Italy together … Kesselring excelled in the art of improvisation, and Anzio may well have been his finest hour.’

John Lucas was feeling comfortable that evening. Reading the reports that were coming through to the Biscayne it was apparent that the divisions were secure and were not under any immediate threat. By the end of the day, as British Guards officers played bridge and slept in their pyjamas, Lucas read with quiet satisfaction that 36,000 men and 3,000 vehicles had been landed. Casualties had been very light – 13 killed, 97 wounded and 44 captured or missing, and the defending panzer grenadiers had been dealt with clinically, producing 227 prisoners. He was also pleased to hear during the afternoon that the port had been opened after the navy had pulled away the hulks of sunken vessels and swept the harbour. As a result of this unexpected speed, supplies were flowing ashore far quicker than anticipated, allowing British vessels to land in Anzio rather than having to struggle with the sand bar. The beachhead was quiet. Exhausted after a trying day, Geoffrey Dormer, a First Lieutenant on the minesweeper HMS Hornpipe, noted in his diary:

D-Day Evening. Things have been very quiet, and it has been a lovely, calm, sunny day, with almost cloudless blue skies. The multitude of ships off the beaches look more like a Review than an Invasion Fleet . . . There are a few columns of smoke rising from the shore, and now and then a dull thud. Sometimes a Cruiser does a bit of bombarding, or a few enemy planes approach.

To the troops on the ground, the beachhead had an ethereal quality to it. Lieutenant Ivor Talbot was in a foxhole close to the Mussolini Canal when he wrote in his diary that evening:

It has been a remarkable day. We landed at 0430 in the darkness and made our way inland. There were the inevitable pauses in our advance, but we were eventually told to dig in for the night. It is now 2200 and I am dog tired but must get round to the men before I sleep. All is quiet as it has been for most of the day. I was not expecting this and I think that I had expected to die. I think that we must be careful that we keep our concentration. The Germans will not allow us to remain here without a fight, but we seem to have won the first day.

Talbot was incorrect in his assessment of 22 January. The Allies had not ‘won the first day’. It had been a draw. What the young Lieutenant had not taken into account was the skilful German reaction to Operation Shingle for whilst the Allies were in an excellent position to develop and consolidate a strong beachhead in preparation for a breakout, Kesselring had successfully begun to build a counterattacking force intent on destroying it. Kesselring drew strength from the knowledge that his build up rate would increase significantly henceforward, whilst the Allies were not only dependent on supply from the sea, but were also under time pressure to link up the two disparate parts of Fifth Army. Lucas, meanwhile, felt confident that he could quickly establish an immovable force at Anzio-Nettuno and could rely on the support of powerful naval guns and airpower. By the end of the first day there were opportunities for both sides, and as such much depended on the actions over the coming days of two risk-averse commanders – John P. Lucas and Eberhard von Mackensen.