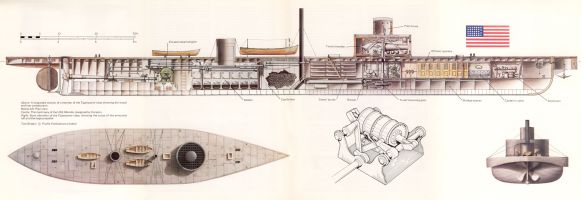

The distinction for participating in the first ironclad-to-ironclad clash must go to the Ericsson turret armorclad USS Monitor, the world’s first mastless ironclad. At the Battle of Hampton Roads (8 March 1862), Monitor faced off Confederate ironclad battery CSS Virginia in one of the very few naval battles fought before a large audience, lining the Virginia shore.

It is popularly supposed that Hampton Roads demonstrated that the day of the wooden warship had ended. It did no such thing; the armored Kinburn batteries had already taken the world’s attention almost six years before, the French La Gloire had been in service for the previous two years, and the magnificent seagoing British ironclad HMS Warrior for six months; and the world’s naval powers at the time had some 20 ironclads on the stocks. It would have been a peculiarly dense naval officer or designer who did not realize by March 1862 that ironclads would dominate the world’s fleets in the very near future. The main question would be what forms those ironclad warships would take.

The historic Battle of Hampton Roads did touch off a veritable monitor mania in the Union: Of the 84 ironclads constructed in the North throughout the Civil War, no less than 64 were of the monitor or turreted types. The first class of Union monitors were the 10 Catskills: Catskill, Camanche, Lehigh, Montauk, Nahant, Nantucket, Patapsco, Passaic, Sangamon, and Weehawken. (Camanche was shipped in knocked-down form to San Francisco. But the transporting vessel sank at the pier. Camanche was later salvaged, but the war was already over. Camanche thus has the distinction of being sunk before completion.) These ironclads, the first large armored warships to have more than two units built from the same plans, were awkwardly armed with one 11-inch and one 15-inch Dahlgren smoothbore. The Passaics were followed by the nine larger Canonicus class: Canonicus, Catawba (not completed in time for Union service), Mahopac, Manayunk, Manhattan, Oneonta, Saugus, Tecumseh, and Tippecanoe, distinguishable by their armament of two matching 15-inch smoothbores and the removal of the dangerous upper-deck overhang.

The eminent engineer James Eads designed four Milwaukee-class whaleback (sloping upper deck) double-turreted monitors: Chickasaw, Kickapoo, Milwaukee, and Winnebago. (Ericsson, on the other hand, loathed multiple-turret monitors, sarcastically comparing the arrangement to “two suns in the sky.”) Eads’s unique ironclads mounted two turrets, one of the Ericsson type (much to Ericsson’s disgust), the other of Eads’s own patented design: The guns’ recoil would actually drop the turret floor below the waterline for safe reloading; hydraulic power would then raise the floor back to the turret, wherein the guns could be run out by steam power. Eads’s two paddlewheel wooden-hull monitors, Osage and Neosho, designed for work on western rivers, were also unique. Although built to Eads’s designs, the two paddlewheel monitors mounted Ericsson turrets. All of the above monitors saw action in the U. S. Civil War. Completed too late for action were Marietta and Sandusky, iron-hulled river monitors constructed in Pittsburgh by the same firm that had built the U. S. Navy’s first iron ship, the paddle sloop USS Michigan.

Ericsson designed five supposedly oceangoing Union monitors: the iron-construction Dictator and Puritan, and the timber-built Agamenticus, Miantonomah, Monadnock, and Tonawanda.

The one-of-a-kind Union monitors were Roanoke, a cut-down wooden sloop; and Onondaga, also of timber-hull construction. Ozark, a wooden-hull light river monitor, had a higher freeboard than any Union monitor and also mounted a unique underwater gun of very questionable utility. None of the seagoing or the one-of-akind monitors saw combat.

Keokuk was an unlucky semimonitor (its two guns were mounted in two fixed armored towers and fired through three gun ports-a revolving turret would seem to have been an altogether simpler arrangement). The fatal flaw was in the armor, a respectable 5.75 inches, but it was alternated with wood. Participating in the U. S. Navy’s first attack on Charleston, South Carolina, Keokuk was riddled with some 90 Confederate shots and sank the next morning.

Aside from riverine/coastal ironclads, the Federals built only two broadside wooden ironclads, New Ironsides and Dunderberg (later Rochambeau, a super-New Ironsides, almost twice the former ironclad’s displacement), both with no particular design innovation. But New Ironsides could claim to be the most fired-upon ironclad during naval operations off Charleston, perhaps the most fired-upon warship of the nineteenth century, as well as the ironclad that, in turn, fired more rounds at the enemy than any other armored warship of the time. The broadside federal ironclad was formidably armed with fourteen 11-inch Dahlgren smoothbores and two 150-pound Parrott rifles, as well as a ram bow. Its standard 4.5-inch armor plate was far superior to the laminated plate of contemporary monitors. Whereas the monitors off Charleston suffered serious damage from Confederate batteries (and semimonitor Keokuk was sunk), New Ironsides could more or less brush off enemy projectiles and was put out of action only temporarily when attacked by a Confederate spar torpedo boat. During its unmatched 16-month tour of duty off Charleston, it proved a strong deterrent to any Confederate ironclad tempted to break the Union’s wooden blockading fleet off that port city, becoming the “guardian of the blockade.” Still, naval historians have tended to ignore New Ironsides and its wartime contributions because of the conservative design.

In light of their technological inferiority to British turret ironclads, it is difficult to understand why the Union’s Ericsson-turret monitors were also built by other countries: Brazil, Norway, Russia, and Sweden either built their own Ericsson-style monitors or had them built in other countries. (The Swedes, naturally enough, named their initial monitor John Ericsson.) The Russians constructed no less than ten Bronenosetz-class coast-defense monitors, and the Norwegians four similar Skorpionens. The Royal Navy ordered a class of four dwarf coastal ironclads that could be termed monitors, but they carried, of course, Coles turrets on breastworks well above the height at which they would have been mounted on Ericsson monitors, and they had superstructures. Furthermore, unlike the monitors, these coastal ironclads were in fact the diminutive template of the mastless turreted capital ship of the future.

The Union monitors, although an intriguing design, were in truth merely coastal and river warships; although several ventured onto the high seas, they only did so sealed up and unable to use their guns. Their extremely low freeboard (a long-armed man could have dipped his hand in the water from the deck) and tiny reserve of buoyancy made them liable to swamping, beginning with Monitor itself, which foundered off the North Carolina coast in December 1862. Monitor Tecumseh went down in less than two minutes after striking a mine at the Battle of Mobile Bay, the first instantaneous destruction of a warship, an all-too-common event in the twentieth century’s naval battles. Tecumseh was also the first ironclad to be sunk in battle, if one discounts two federal riverine armorclads sunk earlier at the Battle of Plumb Point Bend in May of 1862.

In fact, although the monitors might have been impervious to any Confederate gunnery, Southern mines destroyed the only three such warships sunk by the enemy: Patapsco, Tecumseh, and Milwaukee.(Monitor Weehawken foundered on a relatively calm sea in Charleston Harbor.)

The monitors also suffered from an extremely slow rate of fire; Monitor itself could get off only one shot about every seven minutes. Each shot required that the monitor’s turret revolve to where its floor ammunition hatch matched that of the hull; when firing, the two hatches were out of alignment to protect the magazine. And if an enemy shot hit where the turret met the upper deck, the turret could jam, something that apparently never happened to the many turrets built with Coles’s system.

In 1865, the U. S. Board of Ordnance obtusely argued that warships intended for sea service would be best with no armor at all. Yet at that very moment the Royal Navy had deployed five seagoing ironclads, including the magnificent pioneering Warrior and Black Prince, both warships with truly oceanic range, not to mention Defence, Resistance, and the timber-hull Royal Oak, Prince Consort, and Hector. The French, of course, years before had commissioned the seagoing La Gloire as well as Magenta and Solferino, the latter two the only ironclads ever to mount their main battery on double gun decks. (Magenta also has the melancholy distinction of being the first of the capital ships to be destroyed by mysterious explosion, a fate followed by about a score of such warships in the succeeding decades.)

In view of their design faults, plus their inferior and extremely slow firing guns and laminated armor, the monitors were a dead end in naval architecture from the start. The fact that Washington would consider the British sale of just two Coles turret rams to the Confederacy as grounds for war is a strong indication that the administration of President Abraham Lincoln realized the superiority of British-built turret ships to Union monitors.

Post-Civil War USN

The United States was in basically the same geostrategic position as was Great Britain. The British Isles had no land borders to defend and could thus pour most of its defense funding into its navy. The United States had only two very weak military powers along its two land borders and could thus embark on a great naval construction program, centered on battleships, and relegate its army over the years to something about the size of Romania’s.

Yet of all the naval powers, the United States held on most tenaciously to the coast-defense idea. The armored warships of the new navy, in fact, commenced with the construction of no less than ten big-gun coast-defense monitors. The first five of these were virtually Civil War-era near-derelicts supposedly repaired but actually newly constructed in order to circumvent congressional refusal to allot monies for any new warships. (The fiscal situation was so dire that several Civil War monitors were given to shipbuilders as partial payment for the new monitors.) The remaining five new monitors were actually constructed openly as new warships, as Congress voted funds for the new navy. These bizarre warships were armed with 10- inch and 12-inch guns and were heavily armored. They would participate in the bombardment of Puerto Rico and in blockade duty during the Spanish-American War, fairly well fulfilling their coastal purpose. Within a few years, they were universally denounced in the service as practically useless; their one virtue in later years was that their very low freeboard made them excellent submarine tenders. (One unimpressed contemporary U. S. naval officer described monitor Monterey as “a double-acting, high-uffen-buffen, doubleturreted, back-acting submarine war junk. . . .,” drawing “fourteen feet of mud forward and 16 feet 6 inches of slime aft, and had three feet of discolored water over the main deck in fair weather” (Padfield, 129). The French and the Russians also built coastal minibattleships, in limited numbers, but no new monitors. The Royal Navy and the Italian Navy also built monitors, but these warships were primarily ad hoc expedients to mount heavy guns from uncompleted battleships.