15 October 1952 A B-47 photo reconnaissance flight, authorized by President Truman and staged out of Eielson AFB, was flown over the Chukotsky Peninsula. It confirmed that the Soviets were developing Arctic staging bases on the peninsula from which their bombers could easily reach targets on the North American continent.

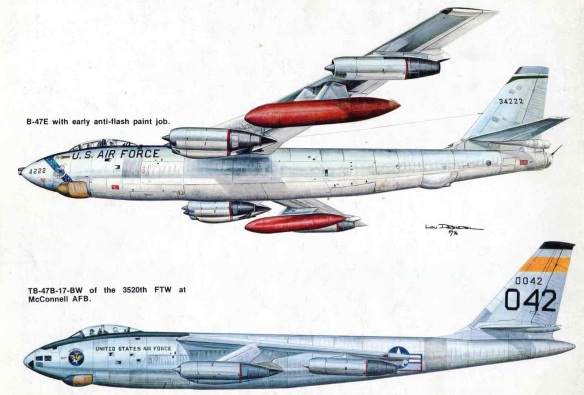

The first four-engine American jet bomber was the North American B-45 Tornado. Produced beginning in 1948, it served in Korea in a reconnaissance role and was in service for a decade. The Boeing B-47 Stratojet medium bomber was one of the most important of USAF aircraft. Sleek and futuristic and the first swept-wing bomber ever in production, the B-47 entered service in 1951.

The first major all-jet bomber was the Boeing B-47, which entered service in 1951; by the end of the decade, 1,260 B-47s were in front-line service with twenty-eight SAC bombing wings. At that time the traditional bomber was large, slow, powered by four piston engines, manned by a crew of ten to twelve men, and defended by numerous gun turrets, but the B-47 completely changed all that. It had swept wings and tail, was as fast as contemporary fighters, was powered by six jet engines in neat pods under the wings, carried a crew of three, operated 3,000 m higher than previous types, and was defended only by a single, remotely controlled turret in the tail. The problem was its relatively short range of 5,800 km, which again was partially compensated by forward deployment (e.g. to the UK) and partly by the large-scale introduction of air-to-air refuelling.

In its efforts to assist the USAF Strategic Air Command (SAC) to build up a potent nuclear strike force in the 1950s, the American aviation industry produced some radical bomber designs, the first of which was the Boeing B-47 Stratojet. All had peculiarities that rendered them dangerous in certain situations, and in the case of the B-47 it was during take-off and landing that the bomber needed extremely careful handling.

The B-47 was a radical departure from conventional design. It featured a thin, flexible wing – based on German wartime research data – with 35 degrees of sweep and equipped with six turbojets in underwing pods, the main undercarriage being housed in the fuselage. It carried underwing fuel tanks, and was fitted with eighteen JATO (jet-assisted take-off) solid fuel rockets to give an emergency take-off thrust of up to 20,000 lb. These were not used during normal operational training, but would have been necessary in a real combat situation to get the B-47, carrying maximum fuel and a 10,000 lb bomb load, off the ground.

The B-47’s undercarriage consisted of two pairs of mainwheels mounted in tandem under the fuselage and outrigger wheels under each wing; the main gear folded up into the fuselage, while the outriggers retracted into the inboard engine nacelles. The arrangement was light and space-saving, but gave the B-47 a tendency to roll on take-off, so that in a strong crosswind the pilot had to hold the control column right over to one side. Steering on the ground was accomplished by the nosewheel, which was adjusted to prevent the aircraft swinging more than six degrees either way. However, the aircraft’s optimum attitude for take-off was the one it assumed as it sat on the ground, and at about 140 knots (depending on its weight), the Stratojet literally flew itself off the runway with no need for backward pressure on the control column. Once off the ground, with flaps up and the aircraft automatically trimmed, the technique was to hold it down until a safe flying speed had been reached and then climb at a shallow angle until 310 knots showed on the airspeed indicator. The rate of climb would then be increased to 4000 or 5000 feet per minute, depending on the aircraft’s configuration.

At its operating altitude of around 40,000 feet, the B-47 handled lightly and could easily be trimmed to fly hands-off. The quietness of the cockpit, the lack of vibration and the smoothness of the flight were noticeable, the only exception being when turbulence was encountered at high altitude in jet streams. Then, looking out of the cockpit, the crew could see the B-47’s long, flexible wings bending up and down – a rather unnerving phenomenon when experienced for the first time.

The B-47 had a spectacular landing technique that began with a long, straight-in approach from high altitude when the pilot lowered his undercarriage to act as an air brake; with its landing gear down the Stratojet was capable of losing 20,000 feet in four minutes. The flaps were not lowered until the final approach, which started several miles from the end of the runway and demanded great concentration. The bomber could not be allowed to stall, yet its speed had to be kept as low as was safely possible to prevent it from running off the far end of the runway. Each additional knot above the crucial landing speed added another 500 feet to the landing run, so the pilot had to fly to within two knots of the landing speed, which was usually about 130 knots for a light B-47 at the end of a sortie.

Ideally, the Stratojet pilot aimed to touch down on both tandem mainwheel units together, because if only one made contact with the runway first the aircraft bounced back into the air. With the wheels firmly down, the pilot used his ailerons to keep the wings level, much as a glider pilot does after touchdown, and as the ailerons were moved the flaps automatically adjusted their position to help counteract roll; the rudder had to be used very cautiously and sparingly or the aircraft might turn over. To slow the fast-rolling B-47, a brake parachute was deployed immediately on touchdown, and the pilot applied heavy braking. In addition, the aircraft was fitted with an anti-skid device that automatically released the brakes and then reapplied them to give fresh ‘bite’. On average, the B-47’s landing roll used up 7000 feet (1.3 miles) of runway.

What could happen if a B-47’s landing went disastrously wrong was demonstrated on 27 July 1956. A Stratojet went out of control while practising roller landings at RAF Lakenheath, Suffolk, and slid off the runway into the bomb dump. Its fuel tanks exploded, killing the crew, and the resultant fire enveloped a storage igloo containing several nuclear weapons in storage configuration, with no nuclear capsules present. The high-explosive (HE) elements in themselves might have caused a sizeable explosion, but the heat-and blast-resistant nature of the igloo prevented damage to the interior and the HE did not detonate. On another occasion, a B-47 was taking off with one nuclear weapon in strike configuration – in other words, with all components in place, but unarmed – when the aircraft’s port rear wheel casing failed at 30 knots. The Stratojet’s tail struck the runway and a fuel tank ruptured. The aircraft burned for seven hours after crash crews evacuated the area, ten minutes after the accident. The HE element of the weapon did not detonate, but the nuclear capsule was destroyed in the fire and some local contamination resulted.

The B-47 suffered many landing accidents during its career, and never quite lost its reputation as a crew-killer. Its mighty successor, the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, also had problems in its early stages, although not with such disastrous results. The turbos had a tendency to explode, causing fires or wrecking sections of the fuselage, and the main undercarriage units were a constant source of trouble. On the ground the bomber rested on four twin-wheel units, all of which were steerable and could be slewed in unison to allow crosswind landings to be made with the wings level and the aircraft crabbing diagonally onto the runway; the trouble was that the main gear trucks had a habit of trying to slew in two different directions at the same time, or of jamming in the maximum 20degree slewed position. The bomber’s big Fowler-type flaps also had a tendency to crack and break under the tremendous sonic buffeting set up by full-power take-offs. Problems such as these caused the B-52 fleet to be grounded on several occasions before they were eventually solved, a process that took two years.

Cold War Secret Flights

In 1958 a fully armed B-47 caught fire on the runway at a SAC base in morocco and produced a considerable amount of local contamination. In 1957, a nineteen-megaton hydrogen bomb was accidentally dropped in an uninhabited area near Albuquerque; the conventional explosives detonated, producing a twelve-foot-deep crater some twenty-five feet across; some radioactive contamination did result. Later years would see accidents in 1959, 1960, 1961, 1964, 1965, and 1968. As with the previous incidents, some contamination occurred, some bombs were recovered, some were not, and SAC servicemen lost their lives. Almost all these accidents received little or no press at the time and some were only revealed decades later.

The American public also knew little of such military incidents over our and our allies’ territory, including the closely held secrets of Air Force reconnaissance, conducted not only in international airspace and waters, but directly over Russia itself. In July 1960, Time magazine headlined the return of two Air Force servicemen who had survived after their RB-47 aircraft had been downed by a Russian fighter in international waters, over the Barents Sea, off Murmansk. Only two of the six-man crew survived, spending seven months in Lubyanka prison before being returned to America. The incident was tragic and definitely served to harden public opinion towards the Soviets.

But there was a good deal more to the overall picture of American aircraft around and over Soviet territory than made it into the Time article. Behind that single story were literally hundreds of signals of intelligence and reconnaissance missions flown by Air Force and Navy aircraft, not only around the borders of the Soviet Union, but for years, directly over Soviet territory, including major cities and military facilities. As early as 1954 a single RB-47 Stratojet had cruised directly over Murmansk, the largest city and major port in northwestern Russia, at forty thousand feet, on a photo intelligence mission targeting several key Soviet airfields. MIG fighters made a series of attacks against the American aircraft, which responded with fire from its own tail cannon. After surviving attacks by several MIG flights, the Stratojet finally took a hit into its wing and fuselage, causing serious damage and loss of fuel. the RB-47 managed to make its way back across Norway to its home field in England, but sounds of the air battle were heard in northern Finland and the report was even repeated in a U. S. newspaper-the Air Force responded by saying that it had no planes in that area. In 1956 a SAC aerial intelligence effort, Project Homerun, dramatically escalated flights over the Soviet Union. Some twenty-one RB-47’s, supported by twenty-eight tankers, flew 156 missions over a route covering a 3,500-mile stretch of Soviet territory. In the final effort of that year, SAC flew a formation of six bombers over Soviet facilities in eastern Siberia with the Soviets totally unable to intercept them. The RB-47 formation took off from Thule, Greenland, and flew over the North Pole and across Soviet territory, landing at Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska. SAC commander General Curtis Lemay had made a definite point to the Soviets: SAC was unstoppable.