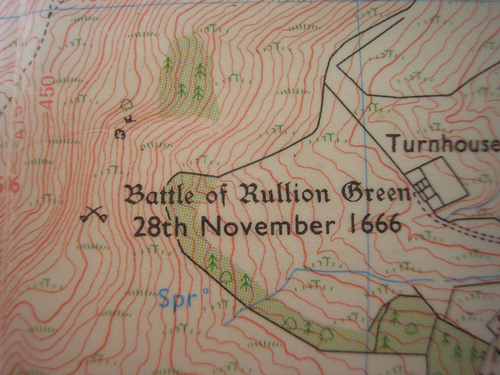

Rullion Green 1666

The prevailing conditions during the march from Lanark were appalling; it was the onset of winter with incessant freezing rain which made the dirt roads almost impassable. Not surprisingly, there were defections along the way, especially when James Wallace learnt that General Tam Dalyell was close on his heels. Vague promises were made; if the rebels laid down their arms, their lives would be spared. The Covenanter leaders had been led to believe that the townspeople of Edinburgh and the surrounding district were favourably disposed to their grievances which, sadly, was very far from the truth; the countryfolk on the outskirts of Edinburgh were at best sullen, at worst aggressive. Reaching Colinton Village about three miles west of Edinburgh, the dissidents conceded defeat; their only safe retreat to Ayrshire lay by way of the Pentland Hills, an area of bleak, inhospitable moors and boggy terrain. On 28 November they camped at Rullion Green; it was a frosty day and snow had fallen the night before. Wallace had intelligence that Dalyell was advancing from the west; messengers from the Duke of Hamilton arrived, pleading that Wallace and his men should surrender; Wallace responded, copying his reply to Dalyell saying that that he would surrender but only on condition that the Covenanters’ grievances would be addressed. Nothing was agreed. By now Wallace commanded only 900 wet, hungry and dispirited men, many of them lacking proper weapons. He formed his force to withstand Dalyell’s attack, expected at any minute; the horse were deployed on each wing, the right commanded by himself, the left by a Major Learmont. The largely unarmed infantry were placed in the centre. With this meagre force how could Wallace hope to defeat Dalyell’s 3,000 well armed, well disciplined and well fed men? Then suddenly Dalyell appeared, forming his dragoons up for the attack.

Hunger and the appalling weather had already sapped the strength and morale of the dissident Covenanters. Wallace had placed his men on Bell’s Hill, a favourable position to confront Dalyell’s troops; Major Learmont managed to repulse the first cavalry charge on the left wing, then a second. Fresh troops were brought up and Dalyell advanced steadily, then he ordered simultaneous attacks on both wings which were successful, bringing his troopers face-to-face with Wallace’s dispirited infantry. The outcome was never in any doubt; as that dreary November day drew to a close, the Covenanters broke and fled, leaving at least fifty dead on the field with about the same number taken prisoner. Dalyell’s losses were negligible. Many of those who escaped death or capture never made it home; some perished in the treacherous Pentland Hills bogs, others were reputedly despatched by the local peasantry. There is a single grave monument which might be said to refute the latter accusation. Near Cauldstane Slap, about twelve miles from Rullion Green, a solitary tombstone existed in 1913 bearing the following inscription:

Sacred To the memory of A Covenanter Who fought and was wounded at Rullion Green November 28, 1666 And who died at Oaken Bush the day after the battle And was buried here by Adam Sanderson of Blackhill.

The site of Rullion Green is commemorated by a single small stone fashioned in the shape of a common and popular seventeenth century headstone; known as the Martyrs’ Stone, it marks the last resting place of ‘fifty true Covenanter Presbyterians’.

Dalyell led the sorry survivors of Rullion Green to Edinburgh where his troopers combed the streets for sympathizers; those who paused to watch the captives being led into the High Street Tolbooth no doubt did so in silence lest they might be implicated and taken into custody. The prisoners were subsequently brought before the High Court of Justiciary where they were interrogated by two formidable lawyers, Sir George Lockhart and Sir George Mackenzie (later known as ‘Bluidy Mackenzie’). Mackenzie put a case for clemency on that occasion as the captives had been granted quarter at Rullion Green. Mackenzie argued that if clemency were denied, no one would ever again trust a promise of quarter. He was overruled on the grounds that the Rullion Green prisoners were not participants in a war, but guilty of an act of sedition. This manipulation of the facts was deliberate on the part of the prosecution which demanded nothing less than blood; the Pentland Rising, the alternative name for Rullion Green, had been proclaimed a rebellion, now it was reduced to a seditious act, punishable by imprisonment and even death. The argument was that the rules of war were inappropriate in this case. Ten of the prisoners were hanged on 7 December 1666; another five shared the same fate on 14 December. After execution the victims’ right arms were cut off, these being the arms with which they had saluted the Covenant at Lanark; the severed limbs were sent to that town for public exhibition. During the subsequent witch-hunt, another twenty-five men were hanged – four in Glasgow and a large number in Ayr. A further fifty were transported in prison ships to Barbados. Rullion Green only served to stiffen resistance; the slaughter on a dismal November morning of men who had followed the dictates of their conscience would not be forgotten.

Even Charles II, the implacable enemy of Scottish Presbyterianism in general and the ‘irreconcilable’ Covenanters in particular, admitted that the Pentland Rising had been clumsily managed; the cruelty meted out only served to create martyrs. So the King made concessions to those who resided in the centre of anarchy in south-west Scotland; prayer meetings could be held as long as they were conducted indoors. Charles hoped that this concession would bring back the stray sheep to a church run by bishops subservient to himself. The hard-core radicals refused to comply. The open air Conventicles increased in number and size until they took on the appearance of military musters rather than prayer meetings. Charles was incensed by this flagrant disobedience; he was determined to bring the irreconcilables to heel with force. Between 1666 and 1673 several of the ringleaders, hellfire preachers like Alexander ‘Prophet’ Peden, minister of the parish of New Luce in Galloway, refused to sign Charles’s Oath of Allegiance to the bishops and by extension the King himself. (The concept of ‘loyal opposition’ had not yet become accepted.) Of the 1,000 Presbyterian ministers preaching in Scotland, Peden and 260 others refused to comply. Peden was obliged to take to the heather, always one step ahead of his pursuers until he was captured in 1673 and thrown into the dank dungeon on the Bass Rock, off North Berwick, East Lothian. In time the Rock would become a prison for others of the same stamp, men like John Blacader, or Blackadder, who died on the Bass Rock for his principles.

At least one positive result from Rullion Green was the appointment of the Earl of Lauderdale as virtual governor of Scotland in 1667; Lauderdale replaced the bitter enemy of the Covenanters, James Sharp, Archbishop of St Andrews known as Judas Sharp to the irreconcilables. Lauderdale pursued a more conciliatory policy towards the irreconcilables and for the moment, peace was restored. However, in 1667, a propagandist book entitled Naphtali was published in support of the Covenanter cause. (Naphtali was the son of Jacob; in the Book of Genesis, he is described as ‘a hound let loose; he giveth goodly words’.) The book listed all the fines that the government’s agent Sir James Turner had exacted from the dissidents; not surprisingly, Turner disputed the facts. Although the author of Naphtali was our old friend Anonymous, the book was written by two men – James Goodtrees, son of a former Edinburgh provost and James Stirling, a Paisley minister. The book was immediately banned and publicly burned. Anyone caught in possession of a copy was subject to a fine of £10,000; it was described as ‘a damned book that came to Scotland from beyond the sea’. Naphtali so incensed Andrew Honeyman, Bishop of Orkney, a prelate in the same mould as Archbishop Sharp that he was moved to publish a counter-blast. In 1668 Honeyman and Sharp were shot at in their coach in Edinburgh; Sharp escaped unscathed, Honeyman was wounded. Their would-be assassin, the Reverend James Mitchell, a minister who had taken part in the Pentland Rising walked away free; he would remain at large until 1678.

During the next three years, Lauderdale’s lenient policy towards the recalcitrant Covenanters grew harsher. Open air Conventicles had become more numerous; what was worse, those who attended them had begun to carry weapons as well as their Bibles. This produced an understandable knee-jerk from Lauderdale; every year of his administration of Scotland from 1670 was marked by ever-increasing severity towards the irreconcilables. For this and other achievements, Lauderdale was elevated to the rank of Duke in 1672. No matter, Conventicles spread from the south-west to Fife, the coastal farmlands of Moray and Easter Ross as well as East Lothian and Berwickshire. In 1677 the Privy Council ordered a half-company (about thirty troopers) of the Earl of Linlithgow’s Regiment to be quartered at Dunbar ready to act against Conventicles being held in the vicinity.

In 1678 the would-be assassin of Archbishop Sharp, James Mitchell was brought to justice. Lauderdale would have spared Mitchell but Sharp insisted that Mitchell be despatched on the gallows in Edinburgh’s Grassmarket, a demand which was duly carried out, making another martyr for the cause of the Covenanters. By way of revenge for Mitchell’s execution Sharp was murdered on 3 May 1679 at Magus Muir, two miles from St Andrews. This episode brought a dismal close to Lauderdale’s administration and caused yet another armed conflict between the government forces and the Covenanters.