Born: October 26, 1800

Died: April 24, 1891

Prussian Chief of General Staff

Understood as the Elder to distinguish him from his nephew, a World War I Commander. Helmuth von Moltke ended up being the architect of Prussian military supremacy in mid-19th century Europe. The son of an impoverished aristocratic Army Officer, he had been brought up in Denmark. Particularly different from the traditional, boorish type of Prussian officer, Moltke was an intellectual with quiet manners and considerable literary talent. He progressed within the Prussian army because Prussia had recognized the requirement for intelligent and professionally capable Staff Officers, and because his cultured manner made him an eligible bachelor, attracting the favor of the royal family. During the first four decades of Moltke’s career, Prussia was at peace and his only firsthand experience in combat occurred in 1839 when he was sent to serve the Ottoman Empire, and he commanded the Turkish artillery in a battle against Egypt.

As chief of the Prussian General Staff in 1857, Moltke revealed impressive energy and drive through radical involvement in organization, planning, and training. However, his personal status, and that of the General Staff, was at first very uncertain. In 1864, when Prussia went to war with Denmark, Command ended up being entrusted to an 80-year-old General who ignored Moltke’s procedure for the conduct of operations. When Moltke was allowed to take control, he brought the war to a swift, successful conclusion. In the process he won the confidence of King Wilhelm I. In 1866, when a major war broke out with Austria, Moltke was free to act as the Commander-in-Chief, using royal decree to issue orders to Army and Divisional Commanders who outranked him in terms of formal social and military hierarchy. Despite his success, some Officers still resented receiving instructions from a man who they regarded as an obscure military bureaucrat.

The rapid defeat of Austria made Moltke a celebrity, and left his authority unquestionable. The war showed his ability to combine prepared planning with a keen appreciation of the chaotic reality of conflict. The key to precious triumph lay within the efficient mobilization of almost 300,000 men and their gear by railway and trains. This was in line with precise timetables drawn up because of the railroad section of the General Staff. This enabled Moltke to seize the initiative from the outset.

Moltke planned for the three armies to maneuver separately, then come together to destroy the Austrian forces in a decisive battle. He understood the need for flexibility and did not attempt to control the campaign at length. His crisp, clear written instructions – early on in the war sent by telegram from Berlin – always allowed commanders a measure of freedom to exercise their own initiative. Likewise, he relied upon the inner circle of his General Staff to make independent judgments in accordance with his strategy.

The climactic struggle of Koniggratz on July 3, 1866 was almost a tragedy, when the last of Moltke’s three armies failed to arrive until halfway through the day. Triumph was finally achieved with their aid, after which Austria sued for peace. When Prussia went to war with France in 1870, Moltke ensured that his Army was the best-trained in Europe, and that its officers and NCOs were imbued with a shared ethos and tactical doctrine. France’s mobilization was a shambles, while Prussian mobilization was faultless. Overcoming temporary confusion and errors as his armies advanced into eastern France, Moltke issued continuously altering orders to meet the quickly developing situation.

By remaining versatile, Moltke was able to lure the courageous but disorganized French field armies into traps at both Metz and Sedan, from which they would not escape. With the surrender of Paris after an extended siege in January 1871, Moltke was recognized as the architect of a military victory that soon made a Prussian-led Germany the dominant power in Europe. The battle at Koniggratz led to 44,000 Austrian casualties, compared with only 9,000 on the Prussian side.

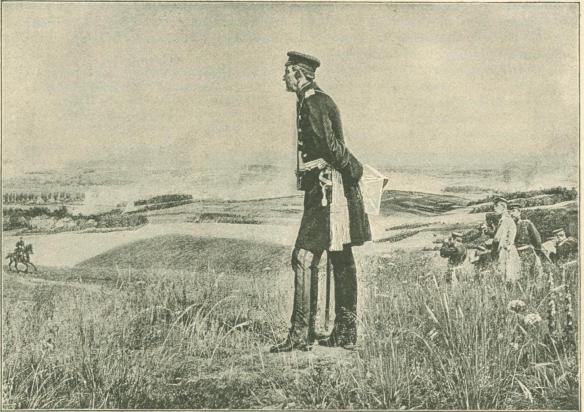

Field Marshal von Moltke before Sedan

The Battle of Sedan

Moltke and his staff traveled with the Royal Headquarters of the Prussian King, Wilhelm I. They kept up with the movements of the 3rd Army under Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia, as well as the Army of the Meuse under Crown Prince Albert of Saxony. Both Crown Princes acted upon Moltke’s orders, although he permitted them broad scope to decide just how these orders were carried out. Moltke was unclear of the intentions of the French. At first, he assumed that MacMahon would fall back toward Paris, and in response prepared to march westward. On August 25, after studying reports in French newspapers and with proof provided from his own cavalry patrols, Moltke decided that MacMahon must have embarked upon a march northeast to join up with Bazaine. Recognizing an unmissable opportunity for a decisive victory, he ordered his armies to travel northward. Using his men assertively to keep in range with the enemy, he was able to catch up with MacMahon, who was crossing the Meuse River near Sedan on August 30.

The following day, Moltke believed that the French would attempt to escape. In order to prevent this, Moltke sent fresh troops across the river both east and west of the French Army – the path northward was blocked by the Belgian border. As the French remained passively inside Sedan, Moltke caught them in a trap.

At dawn on September 1st, Moltke’s armies, outnumbering the French with 200,000 men to 120,000 men, were in place to attack. By early afternoon they had completed the encirclement of Sedan and begin assaulting the French defenses. Although the battle was intense and casualties high, Moltke had no doubt that the end result would be victory. Watching proceedings from a hilltop alongside King Wilhelm, Bismarck, and other dignitaries, Moltke did not issue a single written order that entire day until the battle was over, leaving his Army and Corps Commanders to do their jobs and force the French to surrender.

MacMahon’s dilemma was whether to try to link up with Bazaine’s army or to fall back toward Paris. The French Emperor, Napoleon III, who had joined MacMahon at Chalons, urged withdrawal westward. But MacMahon had chosen a long march around the Prussian flank to meet Bazaine, who he optimistically assumed to be breaking out of Metz. MacMahon’s army was not prepared to execute a maneuver on such a grand scale – they had no maps of the terrain, previously having assumed to be battling in Germany. Slowed by logistical difficulties, they were additionally confused by their Commander’s hesitation.

On the evening of August 27, MacMahon issued orders to turn toward Paris, and then cancelled this command the next early morning. Inexplicably failing to send his cavalry patrol in the direction of the Prussian armies, MacMahon ended up being ignorant of their strength and their position. The unexpected clash with the Prussians on August 30 resulting in the French being forced to complete the hasty, panic stricken crossing of the Meuse. To rest and regroup his weary forces, MacMahon allowed them to stay in Sedan, the fortress town where much-needed food and ammunition were to be found. He could still have made a fighting escape to the West on August 31, but did nothing, while Moltke’s armies crossed the Meuse unopposed. MacMahon designated September 1 as a rest day, but at 4 AM the Prussians launched an attack. MacMahon was wounded early on by an artillery shell. In a debacle typical of the confusion in the French camp, he was forced first by General Auguste Ducrot, and then by General Emmanuel de Wimpffen, to get authorization from the government in Paris. It made no difference who gave the orders, because French military doctrine ultimately determined that there would be no retreat. Prussian artillery dominated the battlefield. Attempts to break out by cavalry and infantry showed immense bravery but could not succeed. Napoleon III humanely insisted on a surrender to save lives. More than 100,000 French soldiers were taken prisoner.