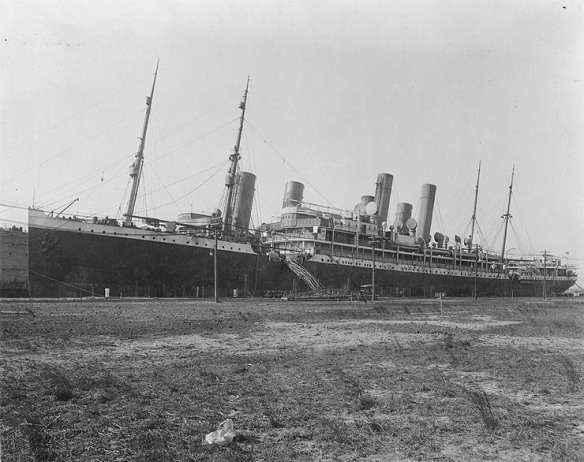

SS Prinz Eitel Friedrich on 28 March 1917, interned at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pennsylvania

SS Prinz Eitel Friedrich, showing port aft gun mount.

Many of the liner’s crew were discharged reservists or civilian volunteers and the voyage west was used to get them used to modern Navy ways and train them in various aspects of their duties. In addition, the guns had to be securely mounted and a gunnery practice programme begun. On 3 September a rendezvous was made with the Karlsruhe’s tender, the collier Assuncion, off Rocas Reef. At 20.30 on 4 September a British liner, the Indian Prince, hove into view and, having spotted the Kronprinz Wilhelm’s guns and naval ensign, stopped without the need to have a shot fired across her bows. As a heavy sea was running, Thierfelder’s boarding party was unable to scramble aboard her until early the following morning. They found that most of her cargo was of value to the British war effort and that being the case, she would, therefore, have to be sunk. In the meantime, provisions, coal and much else would be of use to the raider, although the transfer of these took a over a period of several days because of the sea conditions. The Indian Prince’s crew and passengers were brought across during the afternoon of 8 September. The following morning the bottom was blown out of the ship with scuttling charges and Thierfelder, having been informed that the Etappendienst was now operating, headed south to a rendezvous with several of its supply ships.

On 14 September Thierfelder made the most serious mistake of his career. As Kronprinz Wilhelm was approaching Trinidade Island, off which she was to meet several German ships including another armed merchant cruiser, the Cap Trafalgar, the sound of heavy gunfire came rolling across the water. The source of this was, of course, Cap Trafalgar’s fight to the death with Carmania, but Thierfelder was not to know that. Nor could he have known that, when the gunfire ceased, Carmania had emerged the victor but was so badly damaged that she could not have survived another such fiercely fought contest with his own ship. Suspecting some sort of trap he turned away and began a successful search for the supply ships he had been promised.

Kronprinz Wilhelm had no further contact with Allied shipping until 7 October when the halted the British steamer La Correntina, loaded with frozen meat, off the Brazilian coast. Because of poor weather, it took 14 October to complete the transfer of provisions, coal, passengers and crew from the prize. Also taken from La Correntina were two 4.7-inch guns and their shields. They lacked ammunition but were mounted on the Kronprinz Wilhelm’s poop and used for gun drill, although some of her own ammunition was modified to fire blank cartridges as warning shots. La Correntina was then scuttled, although Thierfelder decided to remain in the area because a radio message informed him that her sister ship had left Monte Video on 12 October and entered the same shipping lane. In the event his wait was in vain and he moved off in search of other victims.

Thierfelder had his own thought on how a raider’s war should be conducted. He avoided areas where he might run into trouble and preferred to use guile rather than force. He would, for example, assume the same course as an unsuspecting merchantman. Neither freighters nor sailing ships could hope to equal the liner’s speed and would expect to be overhauled without attracting suspicion. During this period those aboard the Kronprinz Wilhelm did nothing to attract suspicion. Only when she was running parallel would Thierfelder break out his colours and instruct his victim to stop. No one argued and his guns remained a silent but potent threat. Alternatively, he would remain stationary and transmit distress signals so that his intended prey came to him. The boarding party would examine the cargo for commodities that would be of military use to the Allies and if there were none the ship would be released; if not, she would be scuttled after her coal, provisions, crew, passengers and their luggage had been transferred. Operating off the coast of Brazil or Argentina, the Kaiser Wilhelm II made a total of sixteen captures during her career as a raider and did so, moreover, without the loss of a single life. Ten of these were British, four were French, one was Norwegian and one was Russian. The Norwegian, a barque named Semantha, was, of course, neutral, but she was carrying contraband cargo bound for an Allied port and that ensured her destruction. The Russian schooner Pittan obviously belonged to a combatant nation and was fair game but she was apparently of no interest and Thierfelder released her. Altogether, no less than five of the captures were sailing vessels, which illustrates how much of the world’s cargo still travelled in this way.

After a while, the Kaiser Wilhelm II earned herself such a reputation along the eastern seaboard of South America that fictional accounts of her adventures appeared in the Allied press. These were read with great interest by her crew who learned that she had been sunk in a variety of ways as well as being interned. Other aspects of life aboard were less amusing. Overcrowding had become so bad that Thierfelder sent his reluctant passengers into a neutral port aboard his last capture. A monotonous diet lacking fruit and fresh vegetables was undermining the crew’s health to the extent that symptoms of scurvy had begun to appear.

Regular contact was made with German supply ships in rendezvous points in the vastness of the southern Atlantic, although these became less frequent as the voyage progressed. This ultimately brought the raider’s career to an end. During the morning of 28 March 1915 she arrived at the rendezvous point to find herself alone. She remained there all day and during the evening her lookouts spotted the distant shapes of two British cruisers escorting a cargo vessel. They passed out of sight without anyone suspecting that the freighter was their supply ship, the Macedonia, which had just been captured. Thierfelder waited in vain for several days and finally reached the reluctant conclusion that his supplies of coal and provisions had sunk so low that he could no longer remain operational. He sailed for the east coast of the United States and on 11 April took on a somewhat surprised pilot off Cape Henry. She was directed to a point off Newport News where, with great sadness, Thierfelder rang down Finished With Engines. They had driven Kronprinz Wilhelm over 37,600 miles during her cruise, in which she had sunk 56,000 tons of Allied shipping. She remained laid up at Norfolk Navy Yard and her crew were held in an internment camp nearby. When the United States declared war on Germany in 1917 she was taken over by the US Navy, renamed Von Steuben and served for the rest of the war as a troop transport.

In the internment camp the new arrivals met the crew of the Prinz Eitel Friedrich, which, if not quite in the ocean greyhound class, was still a respectable liner of 8,797 tons displacement, originally belonging to the Norddeutscher Lloyd Steamship Company. It will be recalled that she had been converted to the role of armed merchant cruiser at Tsingtao, being provided with the crews and armament of the gunboats of Luchs and Tiger, a total of four 4.1-inch guns and six 88mm guns. Under Lieutenant Commander Thierichens she had crossed the Pacific with Admiral Graf von Spee’s East Asia Squadron, but had neither taken part in the Battle of Coronel nor accompanied Spee’s squadron in its disastrous attempt to attack the Falkland Islands. Instead, when Spee departed, she had remained off the west coast of South America, taking her first prize on 5 December 1914.

It was naturally a severe shock to learn some days later that, with the exception of Dresden, the East Asia Squadron had been destroyed. Although Dresden was known to have escaped to the east coast, it was believed that she was being hunted by several British cruisers. In the circumstances, therefore, any attempt to contact or cooperate with her could be counter-productive for both ships. Sensibly, Thierichens decided to avoid the coast altogether and head west to Easter Island. On 11 December he picked up the French barque Jean which, usefully, was loaded with coal, followed by the smaller Kidalton next day.

After that, six weeks were to pass before he saw another Allied vessel. He used his time at Easter Island to decide on the best course of action. Little support could be expected if he remained in the Pacific, which was now dominated by the ships of four Allied navies. On the other hand, he was commanding a ship of war and was expected to make the best contribution possible to his country’s war effort. By rounding the Horn far to its south and so avoiding any contact with British ships operating from the Falkland Islands he could enter the Atlantic, raid his way northwards and attempt to reach Germany by breaking through the British blockade of the North Sea.

It was after New Year when Prinz Eitel Friedrich set off to round the Horn, a dangerous passage that she completed without incident. During the next two months she captured and sank eight more prizes as she headed north. As usual, coal and anything useful as well as crews and passengers were transferred before they were sunk. Thierichens does not seem to have used any of his captures to land civilians in a neutral port, but this did not produce excessive over crowding aboard as the average displacement of the prizes was about 3,000 tons, the largest being the 6,629-ton Floride. The crews of ships of this size were usually small and relatively few of them carried passengers.

Thierichens received support from the Etappendienst’s supply ships while running off the Argentine and Brazilian coasts, but north of the Equator there were very few friends to be found, as Thierfelder was also to discover. With fuel running critically low it was apparent that the ship was not going to reach the North Sea, let alone Germany. On 15 March Thierichens took her into Newport News, where the authorities promptly enforced their obligations as neutrals. These limited not only the time that a warship could remain in the harbour, but also the extent that she could replenish her supplies. What settled Eitel Friedrich’s fate once and for all was the arrival of two British cruisers, Cumberland and Niobe, which began prowling the approaches to the harbour just beyond the limit of American territorial waters. Thierichens was well aware that long usage had reduced the builder’s stated maximum speed of 17 knots and that he was very seriously outgunned. He could neither flee nor fight and in the circumstances he had no alternative other than to request internment, which was granted. There the Eitel Friedrich’s career might have ended had not the United States declared war on Germany in 1917 and taken her back into service as the troop transport De Kalb.