König Wilhelm collides [rams] with Grosser Kurfürst

During these experimental years while capital ship design was being blown from one extreme to another on the winds of theory, there was little action experience to go on, and that little was not helpful in solving the major problems concerning first rate ships.

First, there were a few more practical demonstrations of the power of the ram: in 1872 HMS Northumberland, at anchor off Madeira, parted her cable and blew down upon the Hercules, impaling her side upon that vessel’s specially pointed beak which tore a hole ‘a horse and cart could have driven through’. However, she was saved by her compartmentation and did not sink. Three years later there was another collision between British ironclads and this time it was far more serious: both vessels, of Reed’s ‘Audacious’ class, were steaming off the Irish coast one behind the other and about four cables on the port beam of two other ships of the squadron, but rather astern of station so that they had increased to eight knots to catch up. On the port bow was a Norwegian barque. They all ran into dense fog and visibility dropped to less than 100 yards. The Captain of the leading port column ship, Vanguard, was called to the bridge and, anxious about the speed they were making in such conditions, started easing the engine revolutions down and blowing the steam whistle to let the Iron Duke, astern, know where he was. The watch officer of the Iron Duke meanwhile sheered his charge out of line and followed on what he supposed to be the Vanguard’s port quarter as he felt he would be safer; he also increased engine revolutions as, just before the fog clamped down, he had been dropping further astern of the Vanguard. Then his captain arrived on deck, and told of the alteration out of line, remarked ‘That won’t do—get into line again!’ and ordered the helm over.

About the same time in the Vanguard the Norwegian barque was spotted dangerously close and standing across the bow from port to starboard. The ironclad’s engines were immediately stopped and the wheel put over to pass astern of her, thus to port, a manoeuvre which caused her to drop back upon the Iron Duke and across her course. The sailing vessel had hardly disappeared before this new threat was seen less than a ship’s length away. Seconds later the Iron Duke’s ram penetrated the Vanguard’s hull just abaft the watertight bulkhead separating the engine and boiler rooms, a most fatal point as, although the ram stopped some inches short of the inner plating of the double bottom and did not directly breach any main compartment it drove in the armour plates and structure of the ship above, causing numerous relatively small leaks which flooded both vital compartments at some 800 tons an hour, extinguishing the boiler fires in minutes and leaving the ship without any power for the pumps. As the two main compartments filled and others flooded through imperfectly fastened watertight doors it was only a matter of time before the ship went down. The captain set about saving the crew, and seventy minutes after the collision the Vanguard rolled over and sank.

The court martial into her loss considered that the captain should have concentrated his efforts on saving the ship by stuffing sails into the breach, manning the hand pumps and towing her towards shoal water instead of employing the crew hoisting out the boats, and judged that he should be severely reprimanded and dismissed from his command. The captain of the Iron Duke, which had done all the damage despite the steam whistling from the Vanguard, was exonerated from all blame on the grounds that he was justified in regaining station as quickly as possible! These findings come down the years as unjust, unscientific, essentially transitional; the court was composed of nine captains and admirals, only three from ironclads, and all naturally bred in timber seamanship, who apparently ignored evidence that water was entering at the rate of 800 tons an hour and that the hand pumps which they advocated were only capable of discharging 30 tons an hour! Perhaps it was felt necessary to preserve the credibility of British ironclads with a scapegoat; it is not the only example.

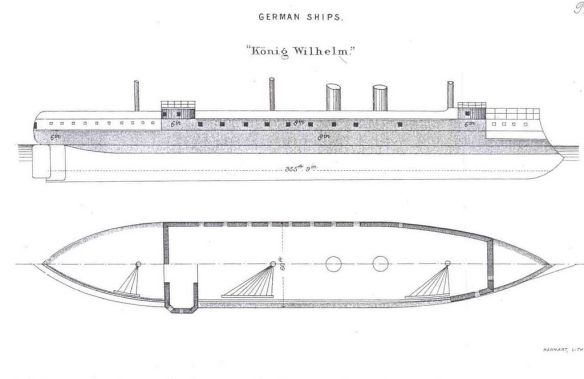

Three years later there was an even worse disaster, this time in a German squadron in clear weather. The squadron was steaming westerly in two columns close off the south Kent coast, the König Wilhelm as flagship followed by the Preussen, forming the port column and one cable to starboard and slightly ahead the Grosser Kurfurst, a rigged turret ship like the Monarch. Two small sailing vessels were beating off the coast to cross ahead of them from starboard to port, and the König Wilhelm altered to starboard to pass under their sterns; as she came to turn back on course, the men at the wheel became flustered, and putting it the wrong way, pointed her straight at the unfortunate Grosser Kurfurst, which was far too close to get out of the way. The ram struck, pierced and tore off the side armour as the Kurfurst steamed ahead, opening her stern sections to a torrent of seawater which took her down in only seven minutes and—because of the shortage of time—284 of the crew with her.

So much for the ram; as Barnaby inferred, the main defence was to keep out of the way—although smaller subdivisions, main watertight bulkheads unpierced for access, and more efficient, quicker-acting, watertight doors were also called for.

As for the gun, the British service had its first and only action experience against an armoured ship before the 1914 War when in 1877 the large unarmoured iron frigate, HMS Shah accompanied by an unarmoured corvette, Amethyst, fought a Peruvian turret ironclad called the Huascar, whose crew had mutinied in support of a bid to overthrow their president, and afterwards interfered with British merchant shipping. The Huascar was a monitor designed by Cowper Coles in 1864, with a single turret rising behind a short forecastle which sloped into a ram below water; her hull was protected by 4-inch armour tapering at the ends and her turret, which contained two 12½-ton Armstrong guns, by 5½-inch armour. Against this, the Shah brought two 12-ton pieces with a theoretical penetration of 10 inches at 1,000 yards and, on each side of her battery deck, eight 6½-ton guns with a theoretical penetration of 7 inches; she also carried a few of the smaller 64 pounders, which formed the sole armament of the Amethyst. However, the British ships, being totally unarmoured and not even protected on the cellular system, had to keep moving and keep the range long, generally between 2,000 and 1,500 yards, to try and avoid being hit, while the low freeboard and frequently end-on position of the turret vessel which steamed about at 11 knots made her an extremely difficult target. In the event the fight, described as partly a following and partly a revolving one, lasted two hours and 40 minutes, during which time the Shah fired 241 rounds and made about 30 hits, mainly on the gear above deck; she did however succeed in hulling the Peruvian vessel with four 9-inch and two 7-inch—2½ per cent of the shots fired; the Amethyst hit her another 30–40 times from 190 rounds. Altogether this was a creditable performance at such a target at such ranges and speeds with such muzzle loading guns and probably justified Colomb’s claim that British naval gunnery was the best in the world. What was disappointing was the low penetration achieved; the only shell to get through the armour was not an armour-piercing shell at all, but a common 9-inch, which pierced a 3½-inch plate and exploded in the timber backing, causing the only four casualties of the action. These results, which compared so unfavourably with theoretical penetrations, continued to be a feature of naval warfare between armourclads, not simply because of inefficient projectiles or charges, mainly because in the words of a French analyst: ‘It is extremely rare, in practice, for a projectile to hit a ship’s armour at exactly a right angle.’

The Huascar, for her part, only fired some eight times and failed to do more than part some rigging on the Shah; she also failed in a ramming attempt as the British ships kept their distance. The lowest range reached was some 400 yards for a brief time, at which point the Shah got off a Whitehead torpedo, the first ever used in action, but at that distance there was little chance of hitting especially as the Huascar outsteamed it! Finally the Huascar retired into shoal water off the town of Ilo where the British ships could neither close because of their deeper draft, nor fire without the chance of putting some shots into the town. The following day she surrendered to her own authorities.

Two years later the Huascar was in action again, this time as a regular member of the Peruvian navy in a war against Chile. She had been engaged on tip and run raids along the Chilean coast when she was caught between two divisions of Chilean ships and forced to fight, which she did most bravely although thoroughly outclassed. The most powerful of the Chilean ships were two Reed-designed belt-and-battery vessels, the Blanco Encelada and the Almirante Cochrane, of 3,500 tons mounting three 12-ton Armstrong guns each side of their armoured batteries. The first to attack held her fire until within 700 yards of the monitor, then unleashed a broadside, one of whose shells pierced the Huascar’s side armour below the turret and, exploding inside, jammed it temporarily and put paid to a number of men working the training gear. Shortly afterwards she hit the conning tower, blowing the captain to pieces, and then came in to ram, failing twice, but pouring in fire at point blank range which pierced the turret and the side armour again. Then she was joined by her sister ship and the Huascar, turning as if to ram and missing by only a few yards received another fearful broadside which completed the shambles within her turret and between decks. With dead and mutilated bodies lying everywhere and both guns’ crews destroyed some of the crew ran on deck waving white towels. In all the Huascar had been hit by 27 heavy shells out of 76 fired; two had penetrated the 5½-inch turret armour from point blank range, and five others had passed through the thinner hull armour and exploded within, an exhibition of decisive gunnery creditable both to the Armstrong guns and the Chilean crews, although these had been under no pressure after the first accurate broadside, and had done their most fatal work at extremely close range. Perhaps most significant (but apparently unnoticed) were the ramming failures.