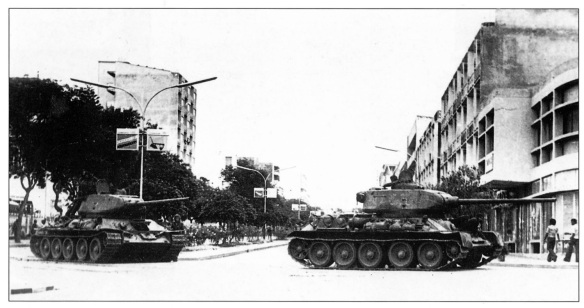

The Cold War fought by proxy – Cuban T-34/85s on the streets of the Angolan provincial city of Huambo in 1975. The Cubans fought on the side of the Communist MPLA in the Angolan civil war, which broke out following the withdrawal of the Portuguese colonial authorities. Despite their age, the T-34/85s gave good and effective service.

In Angola, three nationalist organizations strove for dominance. The MPLA, founded in 1956, was led by Agostinho Neto, a Portuguese-educated medical doctor. The FNLA, established in 1962 as a merger of two regional parties, was led by Holden Roberto, a brother-in-law and protégé of Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, who seized power in the Congo in 1965. UNITA, which broke from the FNLA in 1966, was led by Jonas Savimbi, a Swiss-educated political scientist with a master’s degree from the University of Lausanne. Each of the movements was roughly associated with one of Angola’s three main ethnic groups, although each had members of different ethnic origins, and the MPLA in particular stressed its inclusive national appeal. The MPLA’s stronghold was among the Mbundu in north-central Angola, which included the capital city of Luanda. It also found strong support among Western-educated intellectuals (assimilados), urban workers and the petit bourgeoisie, people of mixed race (mestiços), and a small number of Angola’s 200,000 Portuguese settlers. The FNLA evolved from earlier ethnically based movements in the northwest and was dominated by the Bakongo, who had ties to similar populations in the Congo. UNITA was based primarily among the Ovimbundu in the central highlands.

The three Angolan movements were also distinguished by ideology. The MPLA was avowedly Marxist. Leading members had ties to the Portuguese Communist Party dating to the 1950s. The FNLA and UNITA used anticommunist rhetoric to win international backing but accepted support from China, which was intent on countering Soviet patronage of the MPLA. Internally, UNITA adopted a hard-line Maoist ideology, at least initially. Both the FNLA and UNITA criticized the prominence of whites, mestiços, and Western-educated Africans in the MPLA and presented themselves as the only representatives of authentic African nationalism. Both organizations spurned the MPLA’s offer to establish a common front and systematically attacked MPLA cadres. While the MPLA, and to a lesser extent the FNLA, bore the brunt of the fighting against the Portuguese, UNITA concentrated its efforts on ousting the MPLA from the eastern part of the country, where both movements were recruiting among the smaller ethnic groups. By 1971, Savimbi had signed secret deals with Lisbon in which UNITA agreed to suspend military operations and to collaborate with Portugal against its rivals.

In 1961, the PAIGC, FRELIMO, and the MPLA established the Conference of Nationalist Organizations of the Portuguese Colonies (CONCP), with the goal of coordinating the liberation struggle in all three territories. The three organizations also participated in the 1966 Tricontinental Conference in Havana, where the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America was founded with the pledge to support national liberation and economic development on all three continents.

External Actors

Although Soviet involvement in the Portuguese territories was minimal in the 1960s, Lisbon claimed that it faced a Soviet-backed communist insurgency and sought support from its NATO allies. The NATO countries responded by providing hundreds of millions of dollars in military and economic aid that enabled Portugal to finance three simultaneous wars and bolster its failing economy. By far the largest military supplier, France contributed armored cars, helicopters, planes, warships, submarines, and ammunition. In addition to ships and planes, West Germany furnished weapons and napalm and collaborated with the Portuguese secret police against the liberation movements. As part of the NATO defense pact, the United States provided military equipment to Portugal for European defense. Although Washington stipulated that American equipment could not be used in Portugal’s African wars, Lisbon openly violated the agreement, and Washington did nothing to enforce it. From the Kennedy through the Nixon administrations, American weapons, tanks, planes, ships, helicopters, napalm, and chemical defoliants were used against Africans in the Portuguese colonies, while American military personnel trained thousands of Portuguese soldiers in counterinsurgency techniques.

NATO’s official support for Portugal was countered by a disparate group of nations and nongovernmental organizations that sustained the anticolonial movements. The most significant liberation supporters were the Nordic countries, which included neutral Sweden and Finland as well as NATO members Norway and Denmark. The Nordics established close relationships with the liberation movements and were their main source of humanitarian assistance. The World Council of Churches, whose Programme to Combat Racism established a special fund to provide humanitarian aid to the liberation movements, was another important source of moral backing and material aid. The OAU, established by thirty-two independent African countries in 1963 to unite the continent and eradicate colonialism, mobilized military, economic, and diplomatic support through its Tanzania-based Liberation Committee. Finally, communist countries – most importantly, the Soviet Union, Cuba, and China – responded to the Portuguese onslaught with military assistance to the various liberation organizations.

The War

The richest and most strategic of the Portuguese colonies, Angola attracted the most outside interest during the periods of decolonization and the Cold War. A major producer of oil, industrial diamonds, and coffee, Angola was the site of significant investments by American, British, Belgian, French, and West German firms. The colony bordered Mobutu’s Congo (renamed Zaire in 1971) and South African–occupied Namibia. Zaire and South Africa were determined to install a compliant regime on their perimeters. Angola became a Cold War battleground when the United States, the Soviet Union, China, and Cuba embroiled themselves in the conflict on the eve of Angolan independence.

From the outset, Angola’s three liberation movements aroused interest among the Cold War players. In the 1960s, the United States supported Portugal but hedged its bets by giving token financial and military support to the FNLA. Although American aid was not substantial enough to threaten Portugal’s hold, it did strengthen the FNLA vis-à-vis the better-educated, better-organized MPLA. Indirect support for the FNLA through the American client regime in Zaire proved to be far more significant. Mobutu hoped to use the FNLA and the French-backed separatist movement, Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda, to annex Angola’s Bakongo areas and the oil-rich Cabinda Enclave, thus forming a wealthier, more powerful Greater Zaire. In the early 1970s, China, North Korea, and Romania also supplied the FNLA with weapons and advisors, while China gave further aid to UNITA. Initially the recipient of both Chinese and Soviet aid, the MPLA became entangled in the Sino-Soviet conflict, and opposing sympathies fractured its leadership. The MPLA-Soviet relationship survived but remained tense due to Soviet distrust of the independent-minded Neto. In 1965, a small number of Cubans helped the MPLA in its battles against the Portuguese. In subsequent years, MPLA soldiers received material assistance and military training from China, Cuba, North Korea, and Eastern Europe, as well as the Soviet Union. Soviet disenchantment with the MPLA – due primarily to its internal leadership struggles – led to the cessation of Soviet aid for several months in 1974. Yugoslavia, which prized its independence from the Soviet Union, stepped into the breach and became the MPLA’s main external source of support during this period. As in the cases of Portuguese Guinea and Mozambique, the Nordic countries, especially Sweden, were a significant source of humanitarian assistance – in this case for the MPLA.

The Portuguese coup in April 1974 dramatically altered the lay of the land. China immediately intensified aid to both the FNLA and UNITA, using Zaire as a conduit to send arms, advisors, and military instructors. The CIA followed suit, funneling support to the FNLA through Mobutu’s territory. In August, the Soviet Union announced its moral support for the MPLA but demanded that the movement reconcile factional differences before Moscow would consider providing material aid. By autumn, it was clear that the MPLA would not soon resolve its internal disputes. Concerned by the escalating involvement of China and the United States, the Soviet Union reluctantly threw its weight behind the strongest faction, led by Agostinho Neto.

In fact, Moscow was not anxious to embroil itself in the Angolan conflict. Urging the three movements to resolve their differences through negotiation, the Soviet Union supported an African-led peace initiative. The resulting Alvor Accord, signed by Portugal and the three liberation movements on January 15, 1975, obliged the signatories to form a transitional government that included representatives from all three movements and to hold constituent assembly elections in October. The elected assembly would choose a president, and independence would be granted on November 11, 1975. Twenty-four thousand Portuguese troops would remain in Angola to implement the agreement.

The Alvor Accord was violated almost immediately. The FNLA was the strongest movement militarily, but the MPLA was far better established among the civilian population. It had developed a broader base and achieved greater grassroots mobilization than either the FNLA or UNITA. War would play to the FNLA’s strengths, whereas peaceful political activism would benefit the MPLA. Despite Washington’s public support for the Alvor Accord and the warning by Africanists in the foreign service against choosing sides, Henry Kissinger considered the MPLA to be a Soviet proxy and was determined to challenge it. In his dual role as Ford’s national security advisor and secretary of state, Kissinger showed no interest in reconciliation. The CIA resumed covert support for the FNLA less than a week after the signing of the Alvor Accord, authorizing $300,000 in covert funds on January 22. The money was used to buy vehicles, a newspaper, and a television station – in short, to provide greater means for the politically weaker movement to reach the Angolan people. More significantly, Washington began to provide substantial military and economic support for the FNLA through the Mobutu regime, which had lobbied hard for American involvement. From March through May, the FNLA launched a series of attacks that killed MPLA activists in the capital and elsewhere in northern Angola. Meanwhile, more than 1,000 Zairian soldiers infiltrated into Angola to fight on the FNLA’s behalf. Resisting Portuguese requests that it keep Mobutu at bay, Washington refused to intercede, asserting that it was not the United States’ business to impose policy positions on the Zairian president.

Lukewarm about the MPLA, Moscow responded reluctantly to the American-led escalation. It was only in March 1975, when it became clear that Zaire and the United States planned to exclude the MPLA from the political arena, that Moscow resumed weapons shipments – the first since 1974. By the end of May, a strengthened MPLA was able to expel the FNLA from Luanda, where the MPLA had enormous popular support. In late June, South African intelligence reported that an MPLA victory could be thwarted only through South African support for its rivals.

July ushered in a new phase of the struggle, during which South African and American intelligence collaborated closely, and the United States pressed South Africa to intervene militarily. Moving in tandem, Pretoria and Washington funneled weapons and vehicles valued at tens of millions of dollars to the FNLA and UNITA. On July 14, South Africa authorized a weapons shipment worth $14.1 million. A few days later, the CIA began to channel another $14 million in weapons, tanks, and armored cars, using Zaire as its base of operations. Nearly $3 million of these funds were allotted to reimburse to Mobutu for his part in the war effort. On August 20, another $10.7 million in covert American funds were authorized. Two days later, South African troops crossed the border into southern Angola in pursuit of Namibian guerrillas from the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), who were fighting South Africa’s illegal occupation of their homeland. South African raids would continue through September, as FNLA and UNITA forces assisted South African soldiers in locating and destroying SWAPO guerrillas. The incursions into Angola by soldiers from the apartheid state upped the ante, dramatically altering the political stakes.

As Washington and Pretoria bolstered the FNLA and UNITA, Moscow escalated its support for the MPLA, supplying more arms and military advisors. In September, East Germany followed suit with $2.5 million in military aid, furnishing weapons, instructors, pilots, and doctors. By September 22, the MPLA, with its augmented external support, had halted the advance toward Luanda of FNLA and Zairian troops accompanied by Portuguese mercenaries. By that time, the MPLA was dominant in nine of Angola’s sixteen provinces, including the capital, the coastline from Luanda to Namibia, and the coastal hinterland. Angola’s five major ports, the oil-rich Cabinda Enclave, and most of the diamond-bearing Lunda district were also under MPLA control.

Although Zairian troops had been involved in the Angolan conflict from the outset, foreign intervention took on a new dimension in mid-October when the South African Defence Force (SADF) launched a massive invasion. By the end of the month, an estimated 1,000 South African soldiers were entrenched in Angola. Another 2,000 troops, as well as planes, helicopters, and armored vehicles, were poised on the border. Joined in Angola by FNLA and UNITA soldiers, Zairian troops, and European mercenaries, the South African contingent, with CIA encouragement, began to advance on Luanda, rapidly winning the territory that the FNLA and UNITA had been unable to conquer on their own.

Until this point, Cuba’s response to MPLA requests had been relatively modest. During the waning years of Portuguese rule, Cuba trained MPLA cadres in neighboring Congo-Brazzaville; in the spring of 1975 it sent military advisors to assist in MPLA military planning, and in August it provided $100,000 for weapons transportation. It was only after the South African invasion in October that Cuba responded to the MPLA’s pleas for troops. Unwilling to upset a tenuous détente with the United States, Moscow had refused to supply Soviet troops – or to airlift Cuban soldiers – until after Independence Day, which according to the Alvor Accord would be on November 11. As the agreement disintegrated, it became clear that whoever controlled the capital on Independence Day would determine the government. Convinced that South Africa would take Luanda before November 11 unless impeded by outside forces, Havana was unwilling to wait. On October 23, Cuban soldiers participated in the fighting for the first time. A few days later, Chinese military instructors, who had been training FNLA soldiers in Zaire, ceased their support – embarrassed by their now-public association with the apartheid regime. On November 10, MPLA and Cuban forces held Luanda against an onslaught of 2,000 FNLA and 1,200 Zairian soldiers, more than 100 Portuguese mercenaries, and advisors supplied by South Africa and the CIA. The Portuguese high commissioner transferred sovereignty to “the Angolan people,” rather than to any of the warring movements, and on November 11 the MPLA announced the establishment of the People’s Republic of Angola.

After independence, thousands of foreign troops poured into Angola. Having waited until November 11 to intervene directly, the Soviet Union embarked on a massive sea- and airlift, transporting more than 12,000 Cuban soldiers between November 1975 and January 1976. Moscow also sent military instructors and technicians, along with heavy weapons, tanks, missiles, and fighter planes. Meanwhile, thousands of South Africa troops and hundreds of European mercenaries, the latter recruited and paid for by the CIA, arrived to assist the MPLA’s rivals. In late November, with a final expenditure of $7 million for the Angolan operation, the CIA’s secret Contingency Reserve Fund was depleted. By that time, America’s once-covert role had been exposed. Embarrassed by the imbroglio, especially American collaboration with white-ruled South Africa, Congress passed two bills that banned further funding of covert activities in Angola, and a reluctant President Ford signed them into law. Abandoned by its allies, South Africa withdrew from Angola during the first few months of 1976. Without Pretoria’s backing, the FNLA and UNITA rapidly collapsed. By February 1976, the MPLA, with Cuban assistance, controlled all of northern Angola. Disgusted by the collaboration between the MPLA’s rivals and apartheid South Africa, the OAU and the vast majority of African nations recognized the MPLA government. By the early 1980s, only the United States and South Africa continued to withhold diplomatic recognition.