Volkssturm marching, November 1944.

In August, the Hitler Youth leader, Artur Axmann, issued a call for boys born in 1928 to volunteer for the Wehrmacht. Whole cohorts of Hitler Youths answered the summons and within six weeks 70 per cent of the age group had signed up. Parents may have viewed the call-up with horror, but few tried to stop the teenagers from going. In the earlier years of the war, especially after the victories in the west, military recruitment offices had been besieged by teenagers desperate to sign up and do their bit for the Fatherland; for many this sense of patriotic adventure continued into 1945. Then on 25 September a new people’s militia was announced, the Volkssturm, its name a populist merging of the romantic tradition of the 1813 ‘War of Liberation’ against Napoleon and the traditional Prussian militia, the Landsturm. As military strategists in the 1920s had examined Germany’s failure to make a ‘last stand’ in 1918, there had been calls for just such a ‘total mobilisation’ of the civilian population. Unlike Axmann’s earlier appeal for volunteers, however, recruitment for the Volkssturm was not voluntary, and by the end of 1944 parents were being threatened with legal sanctions if their sons did not enlist. But these threats affected a small minority: by that time most Hitler Youths had already volunteered. As call-up was extended to boys and men between the ages of 16 and 60, the Gauleiters were entrusted with raising this final levy to form a militia numbering up to six million. Its potential reservoir was even larger: if every able-bodied German man had been called up, the Volkssturm would have grown to 13.5 million – greater in size than the Wehrmacht with its 11.2 million officers and men.

The Volkssturm levy, intended to help make good the losses the army had sustained that summer, was simply too large to be equipped. Indeed, the Wehrmacht itself was short of 714,000 rifles in October 1944. At a monthly output of 186,000 standard infantry carbines, German production could no longer keep pace with the ambitions of this ‘rising of the people’. By the end of January 1945, the Volkssturm had managed to accumulate a mere 40,500 rifles and 2,900 machine guns: a heterogeneous array of mainly foreign and out-of-date weapons, often with little, if any, compatible ammunition, giving recruits little chance to practise with live rounds. While more effort was lavished on inducting the teenagers as future soldiers, who were sent to separate training camps, far less went on the middle-aged men, who were treated as cannon fodder; few of them received more than ten to fourteen days’ training. Improvisation was the order of the day: the quadruple batteries of 20mm anti-aircraft guns were frequently converted to infantry use, machine guns from planes remounted on tripods and even flare pistols used for firing grenades.

The flak auxiliaries already included 10,000 women volunteers from the Nazi Women’s Organisation, who ran messages and worked the searchlights and radar guidance systems of the heavy batteries. As boys headed off to train for the Volkssturm, their anti-aircraft positions were often taken over by girls from the BDM and Reich Labour Service. Unlike the smart attire worn by the women already posted to the military telephone exhanges and typing pools, this new levy of female recruits simply inherited the oversized uniforms left by their male forerunners. Now, as German women put on pistols to defend their gun emplacements, the myth that German men ‘out there’ were protecting women and children ‘at home’ completely crumbled. In 1941, audiences at home had unhesitatingly seen the ‘Bolshevik gun-woman’ as a freak against nature and a perversion of women’s vocation to nurture. As German women broke this final cultural barrier, it hardly seemed remarkable any more.

The establishment of the Volkssturm also sat uncomfortably with Nazi measures to protect Germany’s children: what was the point in evacuating them from the cities, only to send them out against tanks on bicycles with a brace of anti-tank grenades strapped to the handlebars? With the nation’s future at stake, service and sacrifice became the overriding virtues. The new Commander-in-Chief of the Reserve Army and of the Volkssturm, Heinrich Himmler, told military recruiters why they should share his determination ‘to send 15-year-olds to the front’: ‘It is better that a young cohort dies and the nation is saved than that I spare a young cohort and a whole nation of 80–90 million people dies out.’ Hitler had warned in his decree establishing the Volkssturm that the enemy’s ‘final goal is to exterminate the German people’ and now his political idée fixe that ‘there must never be another November 1918’ had been put to the test.

As girls as well as boys took their military oaths, after the parade-ground ceremonies the immediate problem was to find uniforms and equipment. In the Rhineland, 15-year-old Hugo Stehkämper and his comrades were given pre-war black SS uniforms, brown Organisation Todt coats, blue Air Force Auxiliary caps and French steel helmets. Across the country, the stores of the Wehrmacht, police, railways, border guards, postal service, storm troopers, National Socialist truck drivers, the Reich Labour Service, the SS, the Hitler Youth and the German Labour Front were all turned over to provide uniforms for the Volkssturm. What made this quest all the more important was the fear that members of the Volkssturm would otherwise be shot as ‘irregulars’, in the way Germans had executed Polish volunteers in 1939.

The regime also realised that the Wehrmacht could learn about ideological control from the Red Army, and in the autumn of 1944 rapidly expanded its own – rather weak – version of political commissars, the National Socialist Leadership Officers. These were volunteers who took on the role of part-time morale-raiser and educator alongside their normal military duties, but they lacked the authority to countermand superior orders. One of the new volunteers was August Töpperwien. Although the high-school teacher from Solingen detested the anti-Christian thrust of Nazism and was appalled by the murder of the Jews, like many other Protestant conservatives Töpperwien still counted ‘world Jewry’ amongst Germany’s enemies. As early as October 1939, he had divided Europe into three blocks, ‘the Western democracies, the National Socialist centre and the Bolshevik east’, and concluded that only Germany would have the determination to defend European culture from ‘Asiatic barbarism’ – this at a time when Germany was allied to the Soviet Union. Believing that ‘World Jewry’ had corrupted the Western democracies, his analysis foreshadowed Goebbels’s later propaganda, but Töpperwien was no Nazi. His views stemmed from conservative nationalism, with its own anti-liberal, anti-Semitic and anti-socialist precepts. Moreover, Töpperwien shared one other fundamental tenet with many of the senior Wehrmacht commanders, like him all veterans of the First World War: he remained committed to preventing any repetition of the revolutionary disintegration of 1918. In October 1944, as the German front lines stabilised again, he noted proudly in his diary, ‘But thank God, the spirit of revolt is still far off!’ Töpperwien had periodically expressed doubts in Hitler’s leadership throughout the war, but by early November he admitted to himself that ‘The clearer it becomes that Hitler is not the God to whom people prayed the more I feel bound to him.’ As Töpperwien worried about people’s loyalty to the German cause, he realised that there was no room for any other leader than Hitler: he might not be a messianic saviour, but no one else could now save Germany.

Another unusual volunteer for the new propaganda role within the Wehrmacht was Peter Stölten. He had, he quipped to his mother, become ‘one of the Doctor’s [Goebbels’s] boys’. By the end of 1944, their number had swelled to 47,000 officers. The prime task of these part-time ‘political commissars’ was to educate their men in an ‘unconstrained will to destroy and to hate’ the enemy. Stölten was certain that the Soviets had to be stopped at all costs. Despite his growing conviction that the war was lost, he forbade himself from doing anything to hasten that result. On the contrary, he admired the Polish fighters in Warsaw for the lesson they had provided in heroic self-sacrifice. He assured his fiancée Dorothee that he had not lost his ‘inborn aversion to NS-sloganeering’ and left ‘all the information sheets’ unread and ‘just improvised’, but his talks may have been all the more credible for not sounding hackneyed; after all, they came from a tank commander with an impressive record of front-line service.

Stölten was not alone in looking to the Poles for an example. Even Heinrich Himmler, entrusted by Hitler with wiping Warsaw from the map, now turned to the Polish ‘Untermenschen’ for inspiration, telling an audience of Party, military and business leaders that

Nothing can be defended so outstandingly as a major city or a field of rubble . . . Here we must defend . . . the country . . . The saying ‘till the last cartridge and bullet!’ must be no idle phrase, but a fact. It must be our sacred duty to ensure that the sorrowful and costly exemplar which Warsaw gave us is enacted by the Wehrmacht and Volkssturm for every German city which has the misfortune to be encircled and besieged.

The comparison was not a hyperbolic one. That autumn, under Guderian’s guidance, German military strategy on the eastern front shifted away from digging continuous entrenched lines, like the positions so recently abandoned along the river Dniepr. Instead, military engineers were using their corvées of civilian workers to turn key cities such as Warsaw, Königsberg, Breslau, Küstrin and Budapest into strongpoints. They were to become the ‘fortresses’ that would hold back the Soviets the way that Moscow and Stalingrad had stopped the Wehrmacht.

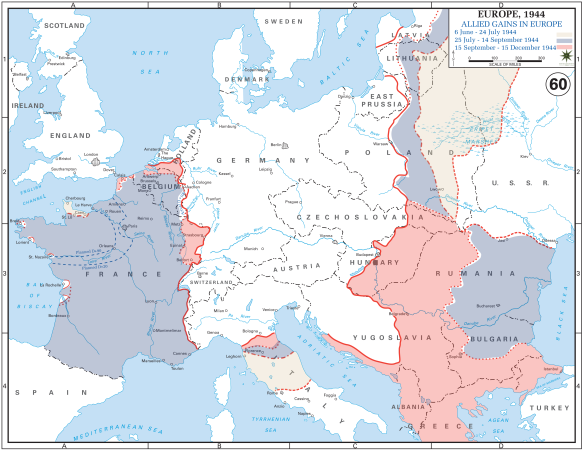

Into October 1944, the new defensive lines held and, against all expectations, blocked the advance of both the Soviets and the Western Allies into the Reich. Partly because of the Wehrmacht’s strong position in the southern Vosges, it was not easy for Patton’s force advancing on the Saar to link up with Patch’s troops in Alsace. The British and American armies also struggled with their own logistical bottleneck: all supplies were still being shipped by road from Normandy and Marseilles. Although the port of Antwerp had been captured on 4 September, before the Germans could blow it up, the Wehrmacht controlled its harbour mouth until November. While the Allies concentrated on reopening Antwerp and shortening their supply lines, the Germans re-equipped the West Wall and began to mass their divisions on the western front.

On the eastern front, in early October the Red Army suddenly turned its northern assault across the marshlands, rivers and tough defences protecting Army Group North in the Baltic states around to the west. As Soviet troops crossed the pre-war German frontier for the first time, penetrating the East Prussian district of Gumbinnen and taking the town of Gołdap and the village of Nemmersdorf, they also cut off thirty German divisions on the Memel peninsula. Scratch units of the new, East Prussian Volkssturm managed to hold the Russian advance around Treuburg, Gumbinnen and along the Angerapp river until mobile reserves could move up to give them support. Then, in mid-October, the Wehrmacht counter-attacked in East Prussia, threatening to encircle the Soviets and forcing them to retreat to the border. With Berlin still over 600 kilometres away the Red Army’s summer offensive had come to a halt along the Vistula and the line of the Carpathians.

Compared to the mass panic which had gripped many of its units on the western front in September, a month later the Wehrmacht presented a very different opponent. Allied commanders were shocked by the stiffening resistance of an enemy that they had assumed was on the point of collapse. At Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force, Eisenhower called a crisis summit in November to ask why nothing had destroyed the ‘will of the Wehrmacht to resist’. The psychological war experts, responsible for debriefing German prisoners of war and profiling their beliefs, were at a loss to explain it. Earlier in the year they had been similarly baffled as the Allies slowly fought their way up the Italian peninsula: there too the morale of their German prisoners had kept rising, the complete oppos-ite of what they had predicted and hoped. Asked if they believed in the existence of ‘new weapons’, in October 1943, only 43 per cent of prisoners had answered in the affirmative, but by February 1944 that proportion had risen to 58 per cent. After the initial shock of the Allied landings in southern Italy, German morale had stabilised. Now, Eisenhower was told, at least half of the captives on the western front still displayed ‘loyalty to the Führer’ and spoke confidently of the Red Army as a spent and defeated force.

It seemed clear that the findings in Italy were now being replicated on the western front. In late August and early September, while ordinary German infantrymen were downcast, morale remained high amongst the core cadre of junior officers, not to mention elite formations such as paratroopers and Waffen SS divisions. But even before German resistance at the front stiffened, most of the prisoners being questioned affirmed the absolute necessity of national defence and the righteousness of their cause. Allied insistence on Germany’s ‘unconditional surrender’ and the leaking of the Morgenthau Plan to strip Germany of all industrial capacity played a part; but the most important factor, now as ever, remained the fear of conquest by the Russians. The exiled novelist Klaus Mann was one of those German-speakers in the US Army tasked with debriefing prisoners of war on the Italian front. In late 1944, he asked his New York publisher: ‘Why don’t they finally stop? What are they waiting for, the unfortunates? This is the question which I don’t just ask you and me, but always pose to them too.’ Other Western experts were equally baffled. Henry Dicks, a veteran of the Tavistock Clinic and the leading British Army psychiatrist, who had interviewed hundreds of German prisoners and written the standard analysis of their outlook, now took refuge in the rather vague concept of the ‘German capacity for repressing reality’. What neither Klaus Mann nor Henry Dicks considered was that, in the absence of a separate peace in the west, German troops considered blocking the British and Americans as essential to holding the Soviets in the east.

In mid-October 1944, the Western Allies could not be sure whether the stiffening German resistance amounted to a temporary pause or a real change in the balance of forces. Military historians now know that the defeats of the summer had ripped the Wehrmacht apart, its fighting power sapped beyond recovery. In the three months from July until the end of September, German military deaths reached a new peak of 5,750 per day. The Army High Command knew in part how disastrous the summer had been – and it was Guderian who first suggested raising an East Prussian Landsturm. Even with bitter fighting in the west, it was on the eastern front that the real haemorrhaging had occurred: 1,233,000 German troops died there in 1944, accounting for nearly half the German fatalities in the east since June 1941.