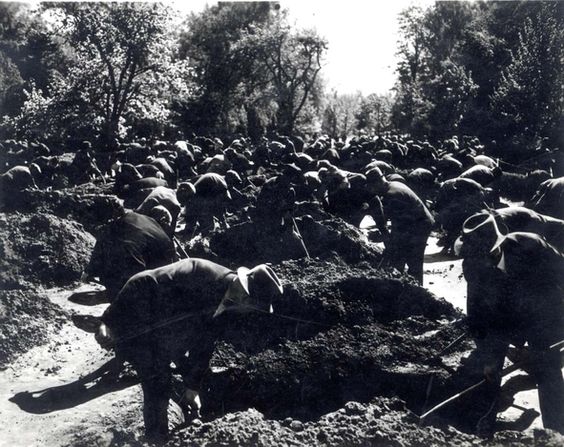

In late August and September 1944, the Germans dug in, literally. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were sent out to dig trenches and build fortifications, a massive effort directed by the Gauleiters in their role as regional Reich Defence Commissioners. By 10 September, there were 211,000 civilians at work on the West Wall alone, mainly women, teenagers and men too old for military service. A further 137 units of the Hitler Youth and the Reich Labour Service, for which both young men and women were liable, were also sent to work. In the east, another half-million Germans and foreign workers were conscripted to dig. In September the theatres were closed across the Reich so that actors, musicians and stagehands could be drafted. While Goebbels tried to protect part of the film industry and Hitler constructed his own list of exceptional artists to exempt, in the Führer’s adopted city of Linz actors and singers were enlisted in the SS and sent off to do guard duty at the nearby concentration camp of Mauthausen.

Applying the lesson of the Soviets’ bitter defence of Stalingrad, in March 1944 Hitler had designated Mogilev, Bobruisk and Vitebsk as ‘fortresses’, which ‘will allow themselves to be surrounded, thereby holding down the largest possible number of enemy forces and establishing conditions for successful counter-attacks’. All three had been lost in the devastating defeats of the summer, but the model had worked better on the western front. Capturing Brest had cost so many American lives – and the port had been so badly destroyed – that the German garrisons were left in control of their other Atlantic ports at Royan, La Rochelle, St-Nazaire and Lorient. As the Wehrmacht fell back to the Vistula in the east, a further twenty towns were now designated as ‘fortresses’ in the eastern German provinces and in Poland. In Silesia, Danzig-West Prussia and the Wartheland, much of the work was done by forced Polish labour. In East Prussia, extensive fortifications dated back to before the First World War but had to be renovated and, where possible, re-equipped. Here the 200,000 Germans racing to finish that task before the autumn rains came complained about the coercive quality of the works. Criticism was mainly aimed at local Party officials who drove out to the sites in their immaculate uniforms and bawled out commands without venturing to pick up a spade and join in. Poor food, accommodation in barns on straw mattresses and excessive hours all took their toll, as German civilians got a mild taste of what they had inflicted on others. But the corvées of labour also renewed a sense of common endeavour, as restaurant waiters and students, printers and university professors trooped out of cities like Königsberg to pick up shovels. By the end of the year, their number had risen to 1.5 million.

The collecting drives for Winter Relief, summer camps and communal stews had long prepared Germans for such an effort. Years of war had completed the training in shared sacrifice. In Lauterbach, Irene Guicking wrote to her husband Ernst, ‘I would so like to set a good example going forwards. I am convinced I would shame the others.’ But looking after two small children left her wondering ‘what I should do so as not to be left on the margins in the total war drive’. At least the German retreat from France meant that her husband could no longer be tempted by the elegant French women. The hills of the Vosges looked so close on the map in her atlas and, gazing at it several times a day, she mused, ‘Just a bit further east and you will be behind the protective border. You know, it must be a funny feeling to know that the border of the Reich is near.’

It was a time of exceptional measures. In mid-July, Goebbels still felt thwarted by Hitler’s reluctance to impose ‘total war’ measures on the home front. But on 20 July 1944 Hitler’s attitude changed, after he narrowly survived an assassination attempt. A bomb planted by Colonel Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg went off in the conference room at his field headquarters in East Prussia, fatally wounding three officers and the stenographer. Like most of the twenty-four people in the room, Hitler suffered a burst eardrum and blast injuries; otherwise, he escaped unscathed. A profound weakness in the conspiracy lay in its lack of high-level support. Whereas in Italy in July 1943 there had been clear consensus within the military that they had to oust Mussolini, no such view had crystallised in the Wehrmacht. Indeed, although they tested out many senior officers, most of the conspirators were officers of mid-rank.

Its organising brain was Henning von Tresckow, who used his role as chief of operations on the Staff of Army Group Centre in 1942–43 to have men like Rudolf Christoph von Gersdorff, Carl-Hans von Hardenberg, Heinrich von Lehndorff-Steinort, Fabian von Schlabrendorff, Philipp and Georg von Boeselager and Berndt von Kleist placed in key positions there. Linked by a web of aristocratic family connections, these younger officers were both held back and tolerated by senior commanders such as Bock, the uncle of Tresckow’s wife, and by Bock’s successor as commander of Army Group Centre, Field Marshal Günther von Kluge, who vetoed their plan to assassinate Hitler when he visited the Smolensk headquarters in March 1943. The plotters failed to win over any high-level military commanders, with the exception of Erwin Rommel and the military commander in France, Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel. This lack of support and comprehension was still more evident lower down the chain of command: the conspirators might have been well connected but they were always an isolated minority.

The plotters attempted to circumvent their weakness by misappropriating an operational plan, code-named ‘Valkyrie’, which had been designed to suppress internal disorder, such as a coup attempt or an uprising by foreign workers, by automatically ordering military units under the command of the Reserve Army to surround government buildings in the capital. It was a fairly flimsy plan. It only took one loyal major, Otto-Ernst Remer, to question the raison d’être of his deployment for the plot to collapse. When Remer went up to arrest Goebbels, he was put through on the telephone to Hitler, whose voice he recognised, and the major immediately accepted responsibility for crushing the plot whose unwitting instrument he had been made. By the early evening of 20 July the rest of the coup attempt had unravelled: the key conspirators were either dead, under arrest or frantically trying to destroy evidence that might implicate them. Remer and his men reached army headquarters in the Bendlerstrasse in time to provide the firing squad. Stauffenberg was in no doubt that his contemporaries would not understand their actions, explaining that he was acting ‘in the knowledge that he will go down in German history as a traitor’. Among his contemporaries, he was not wrong.

News of the attempted coup broke at 6.30 p.m. with a short radio announcement. Then, just after midnight, Hitler’s baritone voice – measured, if slightly breathless – could be heard. ‘German national comrades, I do not know how many times now an attempt on my life has been planned and carried out,’ the Führer began. ‘If I speak to you today it is, first, in order that you should hear my voice and that you should know that I myself am unhurt and well; second, in order that you should know about a crime unparalleled in German history.’ He went on to tell how ‘a very small clique of ambitious, irresponsible, and at the same time senseless and criminally stupid officers have formed a plot to eliminate me and, with me, the German Wehrmacht command’ and to reassure the nation that ‘I myself am completely unhurt. I regard this as a confirmation of the task imposed on me by Providence to continue on the road of my life as I have done hitherto.’ Hitler promised to ‘exterminate’ the perpetrators. The six-minute-long speech and those by Hermann Göring and the Commander-in-Chief of the navy, Karl Dönitz, which followed straight afterwards, were re-broadcast throughout the following day. They came as an earthquake.

In Berlin-Zehlendorf, Peter Stölten’s father expressed his shock tersely, writing to his son, ‘How can they endanger the front so?’ In his diary, he expressed his thoughts more fully: ‘It looks as if they regard the war as lost and want to save what can be saved or what appears salvageable to them. But the whole thing . . . can only lead at this moment to civil war and inner division and create a new stab-in-the-back myth.’ It was a measured response, and he was not alone in fearing defeat or even civil war. According to the SD report from Nuremberg, even those who were critical of the Nazis were convinced that ‘only the Führer can master the situation and that his death would have led to chaos and civil war’. This local report added an interesting note of candour: ‘Even the circles which have looked favourably on a military dictatorship are convinced by the more than dilettantish preparation and execution of the coup that generals are not equipped to take over the helm of state in the most serious of times.’ Clearly, the loose talk about regime change from the summer of 1943 was over. In the streets and shops of Königsberg and Berlin, women were said to have burst into tears of joy at news of Hitler’s survival: ‘Thank God, the Führer is alive’ was the typical expression of relief.

The Propaganda Ministry and the Party rushed to organise ‘spontaneous’ rallies and thanksgivings for Hitler’s ‘providential salvation’. But the huge turnouts and effusive expressions of gratitude seem to have been genuine enough. Even Catholic bastions such as Paderborn and Freiburg, where the Party had previously struggled to hold public rallies at all, recorded unprecedented numbers. Families wrote to each other en masse expressing their relief and joy at Hitler’s miraculous escape: no military censor or propagandist could force them to do so. The Allies, applying ‘scientific’ techniques to measure the success of their own propaganda amongst German prisoners of war, found – to their dismay – that trust in Hitler’s leadership rose from 57 per cent in mid-July to 68 per cent in early August. By this stage, the regime did not make the mistake of confusing such trust and relief with confidence in Germany’s military position. As the President of the Nuremberg provincial court reported, ‘that the mood of the people is very gloomy is no surprise given the position on the eastern front’. But the crisis had a galvanising effect. All the reports confirmed that people expected that ‘now finally’ all obstacles to full mobilisation for total war would be swept aside.

Army Group Centre, from which many of the plotters came, had just lost half its divisions in the huge encirclement battles in Belorussia. The regime was not slow to attribute the defeats to the treachery of these officers. According to the SD reports, ‘national comrades’ now looked admiringly at Stalin’s 1937–38 purge of the officer corps of the Red Army, passing comments such as ‘Stalin is the only clear-sighted one among all the leaders, the one who made betrayal impossible in advance by exterminating the predominant but unreliable elements’. The resolutely plebeian Robert Ley promptly amplified such sentiments in an article in the house paper of the German Labour Front, in which he ranted in terms he had previously reserved for the Jews:

Degenerate to their very bones, blue-blooded to idiocy, repulsively corrupt and as cowardly as all base creatures, this is the clique of nobles which the Jew sends forth against National Socialism, arms with bombs and turns into murderers and criminals . . . This vermin must be exterminated, destroyed root and branch.

Ley’s tirade remained the exception, and Goebbels instructed the press to be careful not to attack the officer corps as a whole. Hitler had called the conspirators ‘a very small clique’ – and so they were. They had lacked the support of any major part of the German state: although many of the plotters came from the army and the Foreign Office, the senior ranks of both institutions remained firmly loyal through the crisis.

In its aftermath, Hitler relied not just on out-and-out Nazi generals, like General Ferdinand Schörner, the new commander of Army Group North, but more ‘apolitical’ figures such as the veteran tank commander Heinz Guderian, whom he had immediately appointed as his new Chief of General Staff on 21 July. The ageing conservative nationalist Gerd von Rundstedt was recalled too, first to chair the officer corps’s purge of its own ranks, and, in September, to take command of the western front once more – this, despite having been dismissed at the beginning of July for telling the High Command that the Allied invasion could not be halted. Despite his deep distrust of the military caste in general and the General Staff in particular, Hitler still knew how to use the loyalty and skills of these men. There was even room for General Johannes Blaskowitz, who had been sacked from his Polish command in 1940 for repeatedly challenging the atrocities carried out by the SS. In the aftermath of the July assassination attempt Blaskowitz had pledged ‘after this dastardly crime to rally to him [the Führer] yet more closely’. Having proved himself during the retreat from southern France, Blaskowitz was entrusted with commanding Army Group H in the Netherlands: with the British in Belgium, it was vital to prevent them from bypassing the Rhineland defences by swinging through the southern Netherlands and into northern Germany. Blaskowitz would repay Hitler’s confidence in full.

When Schörner took command of the 500,000-strong Army Group North in Estonia and Latvia, he issued orders which reflected Hitler’s own apocalyptic views, insisting on the absolute necessity of stopping the ‘Asiatic flood-wave’ of Bolshevism. To halt the German retreat and the desertion of Latvian auxiliaries and to instil obedience through fear, Schörner meted out unprecedented numbers of death sentences for cowardice, defeatism and desertion. For the first time German soldiers did not just face the firing squad. Increasingly Schörner’s command ordered that the condemned should be hanged, with demeaning placards attesting to their crime for all to see: a ‘dishonourable’ death which had so far been reserved for Jews and Slavs. But Schörner was merely an extreme exponent of a growing trend, as Wehrmacht commanders fought to stop their armies from breaking. Even the pious Protestant Blaskowitz turned to draconian methods to halt mass flight. He too would have increasing numbers of his own soldiers shot during the coming months for desertion. On 31 October, Rundstedt proposed placing the relatives of deserters in concentration camps and confiscating their property – so far a measure which had only been used against a handful of families of the July plotters, with most of their wives and children being released within a few weeks.

Although this principle of family liability was also canvassed by other senior generals, the widespread introduction of the policy was ultimately thwarted, and from an unlikely quarter. The SD, the institution empowered to take family members into custody, refused to operate a system of collective reprisals against Germans. Instead of immediately resorting to such measures on the German home front, the Gestapo and SD continued to weigh its decisions on the basis of individual assessments of ‘character’. In Würzburg, for example, the Gestapo refused to act against the parents of a soldier who had deserted on the Italian front because it found no evidence that they were ‘anti-National Socialist’; after dragging out the investigation for nine months, the Gestapo closed the case. Despite new levels of coercion, the Nazi regime was still not ready to deploy at home the techniques of indiscriminate mass terror it had pioneered in occupied Europe.

In other respects, the Nazi leadership emerged from the bomb plot imbued with a more radical sense of purpose, as the most ruthless and efficient group of leaders now formed a virtual ‘quadrumvirate’. With more and more responsibility for the defence of the German regions given to the Gauleiters, Martin Bormann’s control over the Party machine made him a key player. Now adding the command of the Reserve Army to his control over the Interior Ministry, police and SS, Himmler had a near-complete monopoly over the means of coercion within the Reich. Goebbels finally became Plenipotentiary for Total War, a role he had coveted since early 1942. He was now able – at least in principle – to give a new impetus to setting the needs of the civilian economy and cultural consumption aside in favour of unchecked mobilisation for the defence of the Reich. The fourth member of this inner group was Albert Speer, the Minister for Armaments, whose abilities in getting the most out of inadequate resources would be tested as never before. With Hitler focused ever more on micromanaging his military commanders, these four key leaders – all inclined to expand into the others’ spheres of control – would be forced to run the home front in competitive collaboration.