On a pitch-black night in October 1956, the Israeli Air Force pilot Yoash (“Chatto”) Tzidon took off on the commands of his Meteor 13 night fighter, a sleek British-made jet, its black nose cone carrying a rounded radar device.

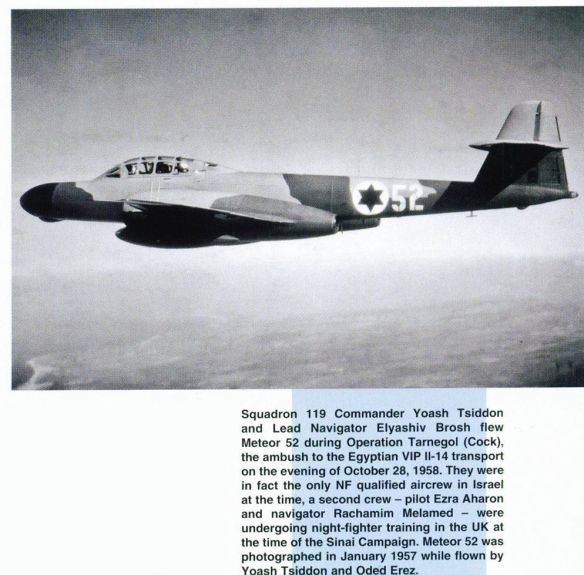

Chatto knew that his dangerous mission was crucial for the outcome of Israel’s next war. Accompanying him in his Meteor was the navigator Elyashiv (“Shibi”) Brosh. The pair knew that their assignment, if it succeeded, would stay top-secret for decades to come. Chatto also already knew that, the next day, October 29, Israel would launch its attack on Egypt. Ironically, his squadron, nicknamed “the Bat,” hadn’t been assigned a significant role; yet somehow, now, at the last minute, it had been tasked with Operation Rooster.

Chatto was accustomed to dangerous assignments. A fighter in the Palmach from the age of seventeen, he had served in a naval unit, departing for Europe in mid-1945 as a founder of the Gideons, an underground group of wireless operators that ran the communications network among the Aliya Bet (illegal immigration to pre-state Israel) command in Europe, illegal-immigrant camps, ships at sea and the Aliya Bet headquarters. He had escorted illegal immigrant ships, established a secret wireless station at a detention camp in Cyprus and participated in a sabotage mission against the British vessel Ocean Vigour, which was involved in expelling illegal Jewish immigrants. In Cyprus he met a nurse from Israel, Raisa Sharira, whom he made his wife. During the War of Independence, Chatto would command a military convoy to Jerusalem and, at the fighting’s conclusion, would enroll in the first pilot-training program in Israel.

As a combat pilot, he had made the transition to jet aircraft, and in 1955 was assigned to train a squadron of “night-fighter all-weather” jets. He called the squadron Zero Visibility.

In the last week of October 1956, Chatto was urgently recalled from England, where he was completing his training for nighttime dog fights. In Israel, his superiors informed him, in total secrecy, of the upcoming Sinai campaign, or Operation Kadesh. “In a couple of days,” they said, “we’ll be at war.”

On October 28, Chatto was transferred to the Tel Nof airbase, closer to the future theater of war. It was there, at 2:00 P.M., that he was urgently summoned to the IAF headquarters in Ramleh. The air force command dispatched a Piper plane to Tel Nof to bring him immediately, even though the trip from Tel Nof to Ramleh lasted barely twenty minutes by car. The head of the Air Department, Colonel Shlomo Lahat, locked the door of his office and explained the assignment to Chatto.

Lahat spoke succinctly, after swearing Chatto to secrecy. “You know,” he said, “that a joint command treaty was recently signed by Egypt, Jordan and Syria. We have learned that the Egyptian and Syrian military chiefs of staff are now conducting talks in Damascus. All the senior staff of the Egyptian Army, Navy and Air Force is participating in the discussions, which are run by Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer, chief of staff of the Egyptian Army.

”Trusted intelligence sources,” Lahat added, “report that the Egyptian delegation will return to Cairo tonight on a Soviet-made plane, Ilyushin ll-14.

“Your mission,” Lahat told Chatto, “is to bring down the plane.”

Chatto understood the tremendous significance of the assignment. If he shot down the plane, the Egyptian armed forces would be left without a military staff and a supreme commander on the eve of a war. The outcome of the entire conflict might hinge on his success.

Lahat expected that the Egyptian plane would choose a flight path far from Israel, outside the range of its fighter planes. He proposed that Chatto take off in his own aircraft and circle above Damascus while he waited for the Egyptian Ilyushin to take flight.

Chatto disagreed. “If they discover my presence, I could get in trouble with their interceptors. Or my fuel tanks could run out before they’ve even taken off.”

Lahat asked what he proposed instead.

Chatto knew that the up-to-the-minute information would be reported by the IDF special units listening to the Egyptian-Syrian communication channel. “Call me half an hour after takeoff,” Tzidon said, “when the plane is over the Mediterranean, in range of our radar.”

Lahat looked at him in surprise. “Do whatever you think is best,” he eventually said.

The Piper jet brought Chatto promptly to Ramat David airbase, where he had parked his Meteor. Shibi Brosh, the navigator, was already there. The pair prepped the plane, even conducting a nighttime test flight. Chatto knew that his principal problem was that the Ilyushin ll-14 was a relatively slow piston aircraft, and that his own Meteor was fast. To hit the Ilyushin, he would need to slow his plane down as much as possible—to landing speed or even less; but at such a speed, his aircraft might stall with its nose upward, and then dive and crash. An idea came to him about how to overcome the problem—by partially lowering the landing flaps, which he practiced midair.

Night fell. The call came several hours after dinner. Chatto, with nerves of steel, had even managed to sleep for about thirty minutes, when, at ten-thirty, he was awakened. The Egyptian plane had taken off from Damascus, he was told, and it had turned toward the sea in a wide arc. It was somewhere at the edge of the Meteor’s range of action, advancing toward Egypt at a height of ten thousand feet, or thirty-two hundred meters.

At 10:45, Chatto and Shibi took off into the night. All of Israel was dark; there wasn’t a trace of moon in the sky. Chatto had never seen such darkness.

The Meteor advanced through the total blackness, with the cockpit faintly illuminated by infrared light so that the pilot’s and navigator’s night vision wouldn’t be diminished. On the two-way radio, Chatto listened to the flight controllers on the ground, identifying among them the serene, restrained voice of Dan Tolkovsky, the IAF commander.

Then the first glitch occurred: Chatto discovered that the fuel in the detachable tanks wasn’t transferring into the main tanks. The plane had taken off with two reserve wing tanks, each containing 350 liters of fuel, and Chatto realized, just like that, that he had lost seven hundred liters. With no other choice, he detached the reserve tanks from the wings and dumped them into the sea. A short time later, he heard Shibi’s excited voice on the internal two-way radio: “Contact! Contact! Contact!”

“Contact!” Chatto radioed to the ground controller.

Shibi sent him precise instructions: “Boogie [unidentified plane] at two o’clock! Same altitude, three miles away, straight forward, moving to three o’clock, now moving to four o’clock, taking a hard right. Lower your speed! Pay attention, you’re closing in fast!”

Chatto couldn’t see a thing, but he followed Shibi’s instructions to the letter, not cluing him in to the problem that would arise when he needed to bring his own speed into line with that of the slow transport plane.

“Eleven o’clock,” Shibi continued. “Descend five hundred. Lower your speed. Distance: seven hundred feet.”

Chatto strained to see. At first, it appeared that he could make out the Egyptian plane’s silhouette; then he discerned a “faint, hesitant” flame emitting from the pipes of the piston engines.

“Eye contact,” he reported to ground control.

Tolkovsky’s voice echoed in his earphones. “I want a confirmed ID of the vessel whose outline you’ve observed. Confirmed beyond a shadow of a doubt. Understood?” The air force commander wanted to avoid any mistake that might unnecessarily cost human lives.

Chatto was now behind the Egyptian plane. Out of the corner of his eye, he spotted its exhaust pipe and maneuvered left, until he could discern the stronger light of the passenger windows. He approached the Egyptian plane, coming to it “nothing less than wing to wing.”

Gradually, the silhouette of the entire plane became perceptible. The shape of the windows in the passenger section resembled those of windows on a Dakota aircraft, but the cockpit windows were bigger, a feature unique to the Ilyushin ll-14. Chatto could also identify the shape of the Ilyushin’s tail.

As he approached the windows, he could make out people in military uniforms walking in the aisle between the seats. Those in the seats also appeared to be wearing uniforms. Flying in close to the Ilyushin had cost him at least ten minutes of fuel, but it had been necessary to confirm the initial identification.

“I confirm ID,” he radioed to ground control.

“You are authorized to open fire only if you have no doubt whatsoever,” Tolkovsky instructed.

The moment had arrived to test the maneuver Chatto had attempted earlier. He lowered the landing flaps by a third, thereby preventing a stall.

“Firing,” he announced into the two-way radio, and pressed the trigger.

Two malfunctions immediately occurred. Someone had loaded the cannons with munitions that included tracing bullets, which, for a moment, blinded him. The second glitch was a blockage in the cannon on the right, which brought about the same effect as an engine breakdown. The Meteor went into a spin, but Chatto regained control and steadied it. Although the Ilyushin had been darkened, he hadn’t lost it, and he could see a flame that flickered from the left-side engine. He reported the hit.

“Finish it off, at any cost,” Tolkovsky’s voice commanded. “I repeat: at any cost!” Chatto knew that if the plane wasn’t brought down right now, Israel would lose the surprise factor during its attack on Egypt the following day.

The Ilyushin was now flying with one engine, much slower than the Meteor’s landing speed. Firing again—with unequal kickback from the cannons, now that one was blocked—would surely throw the Meteor into a spin. Chatto again lowered the landing flaps, increased the power of the engines, and lurched at the Ilyushin. Suddenly another danger materialized: a collision with the Egyptian plane.

Chatto put this fear out of his mind and sped toward the Ilyushin. When he came within fifty meters of it, he heard Shibi shout, “Change course! Change course! We’re going to hit it. I see it on both sides of the cockpit.”

Shibi’s command probably saved them both. At the last second, Chatto squeezed the trigger and suddenly found himself “in the midst of hellfire.”

His shells exploded into the Ilyushin, barely a few feet from the muzzle of the Meteor’s cannon. Fire engulfed the Egyptian plane, shooting across it at the same instant that an explosion transformed it into a fireball. Flaming parts flew past the Meteor. The burning Egyptian plane spun and dived—and, because of uneven kickback from its own blocked cannon, so did the Meteor. Both planes plunged. “A fireball and a darkened plane spun one beside the other, and one above the other,” Chatto later wrote, “both out of control, as if performing a sickening, surreal dance.”

At the last moment, Chatto was able to exit the spin, at an altitude estimated at between 150 and three hundred meters. Simultaneously, he saw the Ilyushin smash and explode into the waves of the Mediterranean.

Chatto climbed to fifteen thousand feet and reported, “Accomplished!”

Tolkovsky wanted to be sure. “You saw it crash?”

“Affirmative. It crashed.” Chatto then looked at the fuel gauge and was horrified. “I’m low on fuel—very low. Give me directions to the closest base.”

He had no idea where he was. The sole radar that located the Meteor was an aircraft battery device on the Hatzor airbase. The battery’s commander took it upon himself to direct “the Bat” to the landing strip.

“I’ll fly in this direction as long as I have fuel,” Chatto radioed.

“You think you can make it?” The controller’s voice sounded dubious.

Chatto attempted to keep things light. “I poured the fluid from Shibi’s cigarette lighter into the fuel tank.”

Tolkovsky cut him off: “No names!”

The fuel gauge dropped to zero. One minute, two minutes, three . . . Suddenly, Chatto could make out the lights of the Hatzor runway, which had been illuminated for him despite the blackout. The plane glided toward the landing strip, and Chatto touched down.

As the plane barreled down the runway, the engines shut off, one after the other. The final drops of fuel had run out, but the Meteor was on the ground.

The base’s whiz technician reached the plane first. “You did it?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“So the war has started.”

Ezer Weizman, the base commander and a nephew of Israel’s first president, arrived immediately.

“Congrats!” Never one to miss a chance to show off, he went on, “Notice, it was only Hatzor that could bring you in.” He added, “They’re waiting for you at headquarters. There’s a problem.”

At headquarters, Lahat, Tolkovsky, and Chief of Staff Moshe Dayan were waiting for Chatto and Shibi. They shook hands.

“What’s the problem?” Chatto inquired.

“At the last minute, Amer decided not to fly on the Ilyushin. He’s going to take off later, on a Dakota.”

The spirit of battle overcame Chatto. “If there’s time, we’ll refuel and go out on a second run,” he offered, and Shibi nodded in agreement.

“It would be too obvious and would expose intelligence sources,” Dayan said. “Let’s leave him be. The moment you wiped out the general staff, you won half the war. Let’s drink to the other half.”

Dayan pulled out a bottle of wine, and everyone toasted.

The 1956 War had thus begun, yet only a handful Israelis knew.

Operation Rooster would remain top-secret for thirty-three years, with details reaching the public only in 1989. The Egyptians never reported the downing of the aircraft, probably because they weren’t aware that it had been targeted; in Cairo, rumors spread that the plane had crashed close to a desert island, and that the army senior staff was still there, awaiting rescue.

Marshal Amer, the Egyptian chief of staff at the time, would commit suicide after the Six Day War.

YOASH (“CHATTO”) TZIDON, COMBAT PILOT

In March 1993, four years after details of Operation Rooster were released, a young Egyptian unexpectedly reached out to Chatto Tzidon. He was Ahmed Jaffar Nassim, the son of an adviser to President Nasser, who had died during Chatto’s operation. The dramatic meeting between the son and the man who had killed his father took place at the Tel Aviv Hilton. The meeting, Chatto later said, was “emotional but without bitterness.” Jaffar, a disabled man in a wheelchair, wanted to know if it was true that his father had fallen into Israeli captivity and been tortured to death after his plane made a forced landing. Chatto clarified that there had been no forced landing, that the operation had been one of “door-to-door service.”

Two years later, Chatto helped Jaffar Nassim gain admission for surgery at Rambam Hospital, in Haifa. “The desire to aid him came out of a feeling of sharing in his sorrow over his father’s death . . . as well as the thought that my own son could have found himself in a similar situation.”

This was just one way in which Chatto showed an unusual streak of sensitivity toward others. His spouse, Raisa, recalls how on the eve of the 1956 War, at a dinner at the home of friends in London, Chatto met the sister of the hostess, an Auschwitz survivor. She was on her way to Israel and remarked “how much she would have liked to see Paris.”

“Why don’t you stop on your way?” Chatto asked. The woman replied, “I have a one-year-old baby. I can’t.”

Chatto had a solution: “I’ll take the baby to Israel.”

And, just like that, he took responsibility for the little girl, caring for and feeding her on the plane. When they stopped in Rome for a layover, he selected an excellent hotel, entrusting the baby to the hotel matron. The next day, he flew on with the infant to Israel. His wife was waiting for him at the airfield. and when she saw a man in a tweed suit with a baby in his arms, didn’t recognize him.

“How did you end up responsible for a baby?” Raisa asked.

He looked at her in surprise. “Her mother had never seen Paris,” he said.

In October 1956, while the Soviet Union is involved in revolts in Warsaw and Budapest against its dictatorship, and the U.S. is in the final stage of its presidential campaign—Dwight Eisenhower is running for a second term—Israel attacks Egypt and achieves a dramatic victory that makes Moshe Dayan a legendary hero. The British and the French, however, fail in their campaign to occupy the Suez Canal.