Ludwig Bockholt

Though streng geheim, the secret purpose of the super Zeppelins being built in the cavernous sheds at Friedrichshafen, the Luftschiff mother base, in September 1917, had long been known to every urchin on the streets of the town. And to Central Power allies as far away as Constantinople. And of course to the Room 40 code breakers, and to the intelligence staff of the British War Office—perhaps alerted, as Woodhall claimed in his Spies of the Great War, by his mysterious Bulgarian/American agent.

An officer of the Kaiserlich Marine’s Airship Service on a train from Friedrichshafen to Berlin was approached by a random passenger with questions about the new Zeppelins: Were they really going to Africa? And would the officer have the honor of going with them? Having been sworn to silence, having even signed very serious papers to this effect, the officer feigned ignorance. But perhaps silence lacked pertinence to a morale-boosting mission everyone in Germany—and elsewhere—already seemed to know about.

By May 1917, von Lettow had become a national hero. Valiantly fighting to preserve German honor in a lost colony, completely isolated by the enemies of the Fatherland, he now lacked nearly everything, even the most basic supplies. His Schutztruppe lived off the land at the edges of the Makonde Plateau in the Mahenge country; most of his askaris fought with rifles and ammunition captured from the British. To the Kaiser and to others in the High Command, von Lettow’s long struggle in an African backwater had become a matter of great strategic importance: Both the Allies and the Central Powers expected the war to end in a negotiated settlement; at the peace talks it would help the German cause if Germany could claim her forces still held the field in Africa, fighting for possession of at least one of her overseas colonies. Unfortunately, von Lettow’s situation now seemed more desperate than ever. How long could he continue the struggle without material aid from the Fatherland?

Professor Dr. Max Zupitza, zoologist and medical doctor, came up with a singular answer to this question. Zupitza, an old Africa hand from the Karl Peters era, had survived both the Maji-Maji Rebellion and the Herero-Hottentot War, and at the outbreak of the Universal Conflict in 1914 was the chief medical officer of German South West Africa. Captured by the British after the fall of Windhoek, he spent a year cooling his heels in a POW camp in Togo, where he heard tales of von Lettow-Vorbeck’s impressive victories in GEA. Exchanged in 1916, he returned to Germany, determined to help the Oberstleutnant in his unequal struggle—but how? Then, in July 1917, Zupitza read in the Wilnaer Zeitung about the endurance flight of LZ 120, which had recently spent more than 100 hours circling the Baltic. Fired with enthusiasm that “an airship could remain aloft to accomplish a voyage to Africa,” he petitioned the Kolonialamt with a wild scheme to outfit a Zeppelin to resupply the beleaguered Schutztruppe.

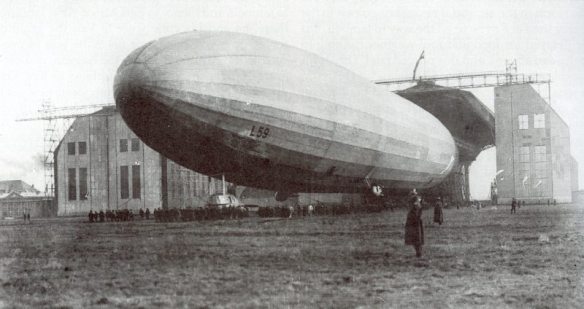

In desperate times, government officials are often willing to listen to wild schemes; the wilder the better. Zupitza’s proposal, forwarded by the Colonial Office to the navy, found favor with naval chief of staff Admiral von Holtzendorff, who passed it on to the Kaiser. The German emperor, nearly as obsessed with von Lettow as Smuts had been, readily gave his imperial blessings. Construction of the first of the super Zeppelins, the ill-fated L57, began in October 1917. Zupitza immediately proposed himself as medical officer for the expedition and was accepted. It seemed fitting that the originator of the Zeppelin-Schutztruppe resupply mission, now code-named “China Show,” should share its fate.

#

They chose Bockholt for his boldness and also because he was expendable. But following the disastrous incineration of L57 at the forward Luftschiff base in Jamboli, Bulgaria, on October 7, 1917, Korvettenkapitan Peter Strasser, the steel-souled mastermind of the Zeppelin blitz on London and commander of the Naval Airship Division, had wanted Bockholt removed from command of China Show. The floundering, storm-racked airship, Strasser believed, had been mishandled by her commander. An inquiry had revealed that, at the height of the gale, with the ground crew still clinging desperately to L57’s mooring ropes, Bockholt had ordered riflemen to shoot holes in the Zeppelin’s hydrogen cells, hoping to release enough gas to bring her down. Not only did this gesture show a poor understanding of basic Zeppelin mechanics (a few bullet-sized puncture wounds wouldn’t make much difference), the bullets probably ignited the volatile hydrogen/oxygen mixture, causing the blaze that destroyed her.

But forces higher up the command structure of the German Navy intervened. Some saw the Kaiser’s hand in it, as Bockholt was not popular with his immediate superiors or his fellow officers—many of whom thought him a selfish careerist who put personal advancement above the good of the service—though all agreed he did not lack courage. Had he not captured the schooner Royal by Zeppelin at sea, an event unique in the war? Still, “Every commander wanted to make the African flight,” so said Emil Hoff, elevator man aboard Zeppelin L42, “and matches were drawn,” selecting another. To no avail; Bockholt kept his job.

“A fine airship commander and a skillful flyer,” Strasser allowed at last, bowing to the Imperial Will. Though he added, “He has not enough experience of the capabilities of airships.”

The same lack of experience characterized L59’s crew—not the best men available, but adequate—and also, like Bockholt, because of their inexperience, expendable. Most, fairly new to the airship service, had been chosen because the mission didn’t come with a return ticket. Once its payload of armaments, ammunition, and supplies had been delivered to von Lettow, L59 would be disassembled on the ground in East Africa and all her parts cannibalized to aid the war effort there, captain and crew included: Like the men of the Königsberg before them, they would join the Schutztruppe and fight alongside von Lettow’s askaris in the jungle until the end.

Strasser privately saw the African mission as little more than a morale-boosting stunt in a military backwater and, though popular with command staff, of secondary importance. All his fearsome energies were directed toward the destruction of England, all his best captains and crews reserved for this imperative. He still believed—as he had written in a memo to Vizeadmiral Reinhard Scheer, commander of Germany’s High Seas Fleet—that “England can be overcome by means of airships, inasmuch as the country will be deprived of the means of existence through the increasingly extensive destruction of cities, factory complexes, dockyards, harbor works with war and merchant ships lying therein, railroads, etc. . . . The airships offer certain means of victoriously ending the war.”

Ironically, in the end, Strasser came to agree with the Kaiser’s choice of Bockholt for China Show. It saved better men for the real Zeppelin war, which to him belonged to the darkened skies over London, to the bombs falling on the Theater District and perhaps on Buckingham Palace itself.

#

L59, pushed by a tailwind from the direction of the German Reich, rumbled south from Jamboli in the freezing dawn of November 21, 1917, at speeds in excess of fifty miles per hour. The great lumbering airship cast her shadow over Adrianople in Turkey at nine forty-five a.m., and over the Sea of Marmara’s chop a short time later. At Pandena, on the southern shore, she picked up the railroad tracks to Smyrna, a steel ribbon barely visible after sunset. At seven forty p.m., L59 pulled free of the Turkish coast at the Lipsas Straits. Now the Greek Dodecanese Islands—Kos, Patmos, Rhodes—passed below, nestled like dark jewels in the black Mediterranean waters, notoriously stormy this time of year. But tonight, the Zeppelin surged forward beneath a clear sky and brilliant stars. Bockholt, who had made his life in the navy, had long ago learned to steer by them when necessary.

L59’s crew of twenty—excluding Bockholt and Zupitza—included twelve mechanics to service the five Maybach 240-horsepower engines (one in the forward control car, two opposed on the belly one-third of the way back, and two aft, each driving a single, massive twenty-foot propeller); two “elevator operators” (the elevators, movable flaps at the tail, controlled the upward or downward incline of the nose cone); a radio operator; and a sailmaker, whose job it was to sew up tears in the muslin envelopes affixed within the belly filled with the flammable hydrogen/oxygen mixture that kept the massive airship afloat.

As in the seaborne navy, watches divided the day into four-hour increments. As L59 approached the island of Crete at eight thirty p.m., a quarter of the crew just gone off watch opened their dinnertime cans of Kaloritkon, a bizarre sort of self-heating MRE. These undigestible, oversalted tubes of potted meat literally cooked themselves via a chemical reaction when exposed to air—heating food over open flame and smoking being strictly verboten aboard the flammable airship. The Kaloritkons, which everyone hated, took much water to wash down, and water was scarce, with barely 14 liters allotted per man for the duration of the voyage.

At ten fifteen p.m., L59 passed above Cape Sidero at Crete’s eastern extremity at 3,000 feet. Then the stars by which Bockholt had been guiding the Zeppelin to Africa suddenly disappeared, blotted out by a solid mass of black, churning clouds, shot through with bright veins of lightning. The Zeppelin headed into this cloud bank and, buffeted by thunderclaps and driving rain, was also suddenly consumed by a strange, vivid flame, cool to the touch, that seemed to dance across every surface of the doped canvas envelope.

“The ship’s burning!” called the top lookout—alarming, but no cause for alarm: This was St. Elmo’s fire, named after Erasmus of Formia, the patron saint of sailors. Technically a luminous plasma generated by coronal discharge in an atmospheric electrical field, it burned a vivid violet-blue and, in nontechnical terms, was entirely beautiful. For uncounted centuries the phenomenon had been interpreted as a sign—of what, exactly, no one could say—of God’s blessing, or God’s curse: It had been seen dancing above the obelisks of the Hippodrome just before the Fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453; it would be seen later, curling along the cockpit and around the spinning props of the B-29 Bockscar as she dropped Fat Boy on Nagasaki in 1945.

Not a quiet phenomenon, St. Elmo’s fire now hissed and sizzled and popped as L59 passed through the storm, fading at last as the super Zeppelin broke into clear air and dazzling moonlight. Now Africa glowed faintly dead ahead, the pirate seaports of the northern coast. For the duration of the storm, L59’s radio antennae, three long delicate wires trailing below her vast belly, had been wound in. Muffled in radio silence, the Zeppelin had been unreachable by any communication from Germany.

As it happened, three and a half hours into the flight, officials at the Kolonialamt having been informed somehow—how, exactly, will become a critical question—of British advances into the Makonde Highlands, last known gathering place of the Schutztruppe, decided to recall the mission. The Kolonialamt relayed this decision to Admiral von Holtzendorff, who broke the news to a crestfallen Kaiser. The Zeppelin handlers at Jamboli, soon informed of the recall, attempted to contact L59 but could not; she had passed beyond the limits of their frail transmitter. Jamboli called this failure back to Berlin: “L59 can no longer be reached from here, request recall through Nauen.” The radio transmitter at Nauen, near Berlin, the most powerful in Germany, then took up the recall message and continued to broadcast it all night long. But with her antenna wound in, deaf to these entreaties, L59 kept on her course for East Africa.

At five fifteen a.m., the sun cracked the rim of earth and the huge airship passed over the African continent at Ras Bulair on the Libyan coast. Miles of desert lay ahead; no Zeppelin had flown across such a landscape before. Now the level wastes of sand and rock stretched monotonously below L59’s keel, from horizon to horizon. Soon, the sun, blazing down, began to dry her canvas skin, still drenched and heavy from the storm. The airship grew lighter as the watery sheen evaporated; lighter still as fuel consumption continued apace. Then the gas in her envelopes, expanding with the heat, blew out the automatic valves into the atmosphere and soon, L59 became dangerously light and increasingly difficult to handle. To compensate, Bockholt flew her “nose down” throughout the day, shifting 1,650 pounds of ballast aft as a counterbalance.

In the late morning, hot desert air rose in bubbles of buoyancy, alternating with heavy downdrafts of cooler air. This caused a roller-coaster effect that made most of the crew violently airsick. Even the hardened navy veterans among them, used to storms at sea, were not immune to the stomach-churning sensation of weightlessness as L59 plunged into the downdrafts and precipitously rose again. Despite all this, L59 plowed ahead and made the Farafra Oasis around noon. This incandescent patch of green slid by below, its date palms rustling in the hot wind. The Bedouin tribesmen gathered there looked up in wild surmise, shading their eyes as the massive Zeppelin slid by overhead, still watching as she disappeared toward the west, the grumbling of her five Maybach engines audible long after she had vanished into the clouds.

Three hours later, the airship reached another oasis, at Dakhla. In this remote place, at the very heart of the desert, many of the tribesmen gathered with their camels around the murky spring had not heard of the war, or been aware that men could take to the air in flying machines. The sight of L59 looming above them like a visitation from a strange new god filled them with fear. (Years later, in 1933, a German aviator passing through the Dakhla Oasis saw crude images of a Zeppelin scrawled on the walls and doors of native huts. Questioning a Bedouin sheikh as to the meaning of these renderings, he was told the scrawl represented the shape of a “powerful sign from the heavens,” which had appeared twenty years before, and that it was worshipped as “a herald of Holy Grace.” Even now, he said, his people watched the skies for its return.)

From Dakhla, where apparently L59 had just inspired its own cargo cult, Bockholt aimed for the Nile. Flying across the endless desert, some of the men in this last era before the ubiquity of sunglasses had gone half-blind from the dazzling glare of sun on sand. Others had been visited with splitting headaches. A few, mesmerized by the persistent drone and the featureless monotony passing below, had become prey to hallucinations: Mirages rose out of the desert, ancient cities, half as old as time, full of jinn out of the Arabian Nights.

Meanwhile, the prosaic Bockholt in the forward gondola used the ship’s shadow crawling along the desert floor as a navigational tool. L59’s exact length, known to the millimeter and factored into a preset equation, measured both ground speed and drift. The Zeppelin sailed through the hot afternoon toward the Nile at sixty miles per hour, functioning perfectly until four twenty p.m. when a juddering sensation preceded the failure of her forward engine. Presently, the big propeller spun to a stop. Mechanics soon determined the reduction gear housing had cracked; they repaired it as best they could but took the engine out of service for the remainder of the journey. Now L59’s radio could not send messages, as this engine drove the radio generator—though radio signals could still be received.

Just before dusk, a flock of flamingos, vividly pink in the setting sun, flapped below L59’s nose cone; a moment later the marshes of the Nile came into view and the airship flew over mile after mile of verdant wetlands. Bockholt made for the great river, crossing over it at Wadi Halfa. Here he turned south, skirting the Nile’s broad flow and droning onward toward Khartoum and the Sudan beyond the last cataract.

Flying a Zeppelin is a difficult undertaking under the best conditions: Gas expands and contracts according to changing temperatures; lift and buoyancy fluctuate; all must be counterbalanced ceaselessly by the release of ballast water, the measured shifting of cargo, the canting of nose or tail via clumsy elevator flaps—and all this becomes doubly difficult over the desert. Bockholt had lightened his airship by 4,400 pounds of ballast in the last full heat of day and had even tossed some boxes of supplies overboard. He knew the rapidly cooling temperatures of the desert at night would contract the gas, causing the Zeppelin to sink. To counterbalance this sinking effect, he had planned to fly the ship at four degrees “nose up” on her four remaining engines.

But he had not counted on the humid, dense air of the Nile Valley. Even at 3,000 feet, ambient temperatures had reached sixty-eight degrees by ten p.m.; they rose steadily after midnight and still L59’s lift capacity gradually diminished. Finally, at three a.m., L59 began to lose altitude precipitously. The engines stalled. Forward thrust gone, the Zeppelin sank through the atmosphere from 3,100 feet to just under 1,300, not high enough to clear a looming desert escarpment; a minute later, her main radio antennae sheared off upon contact with an outcropping of red rock.

Now Bockholt ordered his crew to lighten the ship even further. With all engines stopped, 6,200 pounds of ballast and ammunition went overboard. The crew watched cases of ammunition, much needed by the Schutztruppe, shatter and explode on the ragged slopes below. But this sacrifice had its desired effect: Gradually, the sinking super Zeppelin stabilized; slowly, she rose into safer atmospheres:

“To fly steadily at 4 degrees heavy at night can easily be catastrophic, especially with sudden temperature changes in the Sudan, as at Jebel Ain,” Bockholt later confided to L59’s war diary, “particularly if the engines fail from overheating with warm outside temperatures. . . . Ship should have 3000 kg of 4 percent of her lift for each night to take care of cooling effect.”

Clearly, it was a complicated business.