The thick darkness over Boston had just begun to dissolve with the first wash of daylight from the east, casting the hint of a glow over the rolling meadows of Noddle’s Island. For nearly a week, Noddle’s had been devoid of life, the Williams house and its outbuildings reduced to ash and charred jutting timbers, the sheep and horses and cattle all gone. But aboard the twenty-gun sloop HMS Lively, no one paid much attention to the dead expanse of land to the east-northeast. All eyes were fixed instead on the shadows off the port quarter, on the slopes near Charlestown, just a few hundred yards northwest of where the Lively rode gently at anchor in the Charles River ferryway.

Charlestown itself was no more alive than Noddle’s, a mournful ghost of a village, its deserted houses and shops and its lifeless wharves shrouded in black silence. Or mostly silence. From the hills above the town floated sounds that were just barely there, not quite masked by the slap of the river against the ship’s sheathing, by the creak of spars and tackle . . . the sounds of digging, the lurching rhythm of mattock and spade overturning parched rocky soil, carrying lazily down through the warm, pungent air above the Charles.

It was now just about four o’clock in the morning, eight bells, the hour when in more peaceful times the watch above decks would change. The sounds had begun some time after midnight. Clearly the provincials were up to some mischief on the Charlestown hills. But until daylight betrayed them, there was nothing that the Lively could do to interfere. No sense in throwing broadsides blindly into the dark toward an invisible foe. That would be a waste of good powder and shot.

Then the dim light of daybreak gave the lookouts aboard the Lively their first glimpse of the commotion on the hills. Hundreds of silhouetted figures scuttled around a great raw gash in the earth. A fort had emerged overnight atop the hill closest to Charlestown, in the tall, unkempt grass of the neglected cow pasture. No one could make out its shape or its dimensions—it was still too dark for that—but it was most likely a simple affair. Simple but definitely functional. And so purposefully audacious. The rebels could have thrown up fortifications elsewhere on the peninsula, sites that were safer, more defensible, sites that would have afforded some protection to the base at Cambridge. Yet they chose a hilltop within easy range of the Lively, tugging at her cable midstream. The fort was an overt challenge.

A couple of nights before, the Somerset—a sixty-four-gun ship-of-the-line that dwarfed the little sloop—had guarded the ferryway, but Graves was so deeply haunted by the Diana’s fiery end that he’d ordered the Somerset withdrawn to the safety of deeper waters farther out in the harbor. The Charles River ferryway was narrow and shallow; there was just too much danger that the Somerset would run aground as the Diana had. The Somerset could not be allowed to share the Diana’s fate. On the sixteenth—just the day before—the Somerset left the ferryway and went to her new anchorage. The Lively would face the rebel challenge alone.

The Lively’s skipper, Captain Thomas Bishop, stood at the quarter-rail with spyglass raised to his eye, but he did not take much time to marvel at the resourcefulness or daring or arrogant stupidity of his enemy. He would act, and act quickly. The captain’s pride still smarted from the sharp blow it had received from Admiral Graves less than two weeks before. Bishop had had the great misfortune to become embroiled in a trifling dispute with the commander of the ill-fated Diana, Lieutenant Thomas Graves. Bishop had done nothing wrong—every officer on post knew it—but that hardly mattered when his accuser was the admiral’s nephew. A court-martial was inevitable, and while the court sitting in judgment in the Somerset’s stateroom sympathized with Bishop, there was no way that the captain could evade the admiral’s sputtering, foul-mouthed wrath. Bishop didn’t want to endure that again. But he also knew an opportunity when he saw one, and an opportunity to redeem his bruised reputation was staring down on him from the heights of Charlestown.

The crew was no less eager. Here was a chance for action after months of dull routine, patrolling the waters off Boston and in the harbor as well. The noxious miasmas arising from the great stinking swamps of the Back Bay made the already grinding boredom unbearable. To a man, too, they were hungry for revenge. Each one of them knew precisely what had happened to the Diana three weeks earlier, even if they hadn’t actually seen the last painful hours of her humiliating end . . . a king’s ship, beached and rolled over on her beam ends, abandoned by her crew, Yankee thieves crawling all over her careening hull as they looted her. Even worse, they burned her. It was an insult to every ship and every tar in the fleet.

Bishop did not wait for orders from Graves. His crew was ready. Half of them had been awake and on deck, anyway, pursuant to the admiral’s orders. The rest had since been piped up from below. The gun crews stood to their pieces, the sleek nine-pounders of the Lively’s starboard battery. Charged and shotted, ten black muzzles protruded menacingly from the gaping square maws of the gun ports. The rest of the crew scrambled to bring the ship about on her cable so that the starboard battery could bear on the hilltop fort.

Within minutes the Lively stood parallel to the rebel earthworks. Bishop studied the target one more time as the gun crews tried to get the range, and then he gave the order to open fire.

The explosion shook the placid dawn. The Lively’s entire starboard side erupted in a vivid sheet of flame, horizontal pillars of acrid white smoke cascading from each muzzle, merging to form a single billowy mass that drifted over the surface of the water, carried by the light morning winds toward the beach. The deck shuddered as the long nines, each gun and carriage weighing nearly a ton-and-a-half, leapt violently backward, slamming hard against the massive breeching ropes and tackle that absorbed the shock of the recoil. Nine-pound iron shot flew over the Charles with an unnerving screech, arcing invisibly—for unlike explosive shell, cast-iron solid shot did not trail a telltale corkscrew of flame and sparks.

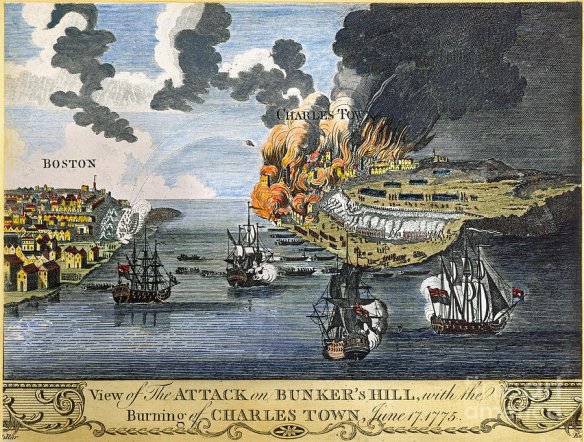

The battle for Charlestown had begun.

General Howe issued his orders at seven. All of the “flank companies”—meaning the light infantry and grenadiers, encamped together as a body on the Common—plus five infantry regiments and one of the Marine battalions were to be dressed, armed, and ready to march to one of two embarkation points in the city.

Now for transportation and naval support—both essential components of a successful amphibious assault. Samuel Graves did not attend the Council of War at Province House that morning. Most likely Gage intentionally left him out; the two men did not get along well, and Gage didn’t need the admiral’s input anyway. But Howe did. The two men met aboard the Somerset, then moored in the harbor.

Graves had been awake even before the Lively’s first broadside, catching up on correspondence and routine paperwork, so both he and Howe were already quite tired at the very beginning of what promised to be a long day. Still it was an amicable and productive meeting. Howe hoped very much that the Somerset and the other larger ships, the Boyne and the Asia, could bring their guns into play, and Graves hoped so, too: the massive thirty-two-pounders on the Somerset and Boyne could wreak havoc on the rebel fortifications . . . if they could reach them. All of the third-raters drew too much water; it was dangerous to send them in the shallows of the Charles and the Mystic, and even then it was doubtful that the lower-deck batteries on these big ships could be elevated high enough that their projectiles would hit the crest of Breed’s. Graves reluctantly conceded that the big ships would be of no use that day, except for the boats, men, and ammunition they could supply. So the Somerset’s skipper detailed thirty-eight tars to man the armed transport Symmetry and her battery of eighteen nine-pounders; another twenty left the Somerset to handle the sloop Falcon, while men from the flagship Preston took over the tiny sloop Spitfire. All was improvised; nothing was as Graves or Howe would have preferred it. “As this Affair was sudden and unexpected,” Graves noted sadly, “there was no time for constructing floating Batteries, or Rafts of real Service, as any such would have been a work of some days.”

The remaining craft—the sloops Lively, Glasgow, Falcon, and Spitfire, the transport Symmetry, and a handful of smaller vessels—would perform the primary task: covering the landing. If the ships could destroy or substantially damage the rebel fortifications, that would be a big plus, but the essential thing was to keep the rebels pinned down so that they didn’t make trouble for the Regulars when they waded ashore. Charlestown itself was another consideration. Howe felt that the rebels could take cover in the deserted buildings and harass the British as they deployed. The ships could guard against that, too.

Could Howe and Graves have made better use of their ships? Undoubtedly. As events would prove, a couple of smaller craft placed in the Mystic estuary could have done great damage to the rebels, and perhaps even changed the course of the battle. But Howe and Graves were reacting to what they knew that morning, and their disposition of the warships reflects that. Still, it is impossible not to find a trace of fault with the general and the admiral for not considering the possibility.

The ships alone, though, could not win the battle, no matter how they were situated around the Charlestown peninsula. Ships could not take ground. If the British wanted the heights, no matter how many tons of cast-iron shot the warships hurled at the Americans, sooner or later foot troops would have to land on the peninsula and take physical possession of them.

So everything, the success or failure of the British attack, would come down to the individual Redcoat—his resilience, his fortitude, his courage, his discipline and obedience. Yet even the common British soldier suspected, just as Gage did in his heart of hearts, that the king’s army was shockingly unprepared for what lay in store for it that day.

Even before the guns on the Lively opened up, grumbling began to ripple through the mass of men in the redoubt. Surely this was no accident. Surely their officers had led them to this spot to die, to be sacrificed for some purpose they themselves couldn’t discern, some end in which their individual lives counted for no more than so many hogs led to the pens at Cambridge Store. “We saw our danger, being against 8 ships of the line and all Boston fortified against us,” fumed Peter Brown, still angry as he recounted the events more than a week later. “The danger we were in made us think there was treachery, and that we were brot there to be all slain, and I must and will venture to say that there was treachery, oversight or presumption in the conduct of our officers.”

Perhaps Brown waxed theatrical. There were no “8 ships of the line” facing Charlestown, no eight ships of the line in all of Boston Harbor. The danger was not quite so dire as Brown thought. Nor did the American officers intend anything insidious, nor any stratagem that required the wholesale sacrifice of American lives. There had only been the sins—the grievous sins—of poor thinking, ill-conceived planning, and amateurish generalship. The American commanders had bitten off more than they could chew. And, amazingly, those commanders never fully grasped the fatal depth of their collective mistakes and miscalculations until it was just about too late.

As the maddening, paralyzing suspicion of treachery infected the men in the redoubt, the storm broke over the river.

It was not a surprise to the men, for all knew that the British would not let their deed go unpunished. But for men who had never before experienced an artillery bombardment—at least not one aimed directly at them—it was still a great shock. Those who had been fearfully watching the Lively’s silhouette hulking ominously in the Charles ferryway first saw the flash, the oddly silent explosion of orange blossoming for a fleeting moment along the sloop’s starboard side. Then, almost in the same instant that the deafening report of the nine-pounders buffeted their ears, the balls came flying among them.

In broad daylight, solid shot from medium and larger cannon were perfectly visible—their size, the laziness of their flight, and the arc of their trajectory made them appear almost harmless to the uninitiated. More accurate—or luckier—shots might whistle past their ears, or bury themselves harmlessly into an earthen parapet. Shot that fell short of its target was just as likely to skip along the ground, continuing its flight in a series of bounds until inertia or a substantial target halted it.

But in the half-light of daybreak, the invisibility of the nine-pounder shot made them truly terrifying. Men whose fears were already magnified by hunger, thirst, and fatigue found the experience all but unbearable.

Mercifully, the Lively’s initial bombardment caused scant physical damage, injuring no one and wrecking nothing of value. The moral effect, though, was not trifling. The bombardment left the redoubt’s defenders dazed; they would have proven to be utterly useless if put to the test at that moment. Many if not all of them might have sought refuge in flight. Thank God they were not left to their own devices.

For Prescott had also perceived the trap into which he, Gridley, and Putnam had led their men, at just about the same time that Peter Brown and his friends began to suspect treachery. To his credit, Prescott did not waste time nervously dithering between possible choices. He was no great tactical genius, but he knew something of fortifications and siegecraft from his time at Louisbourg, and most important, he was level-headed and calm. He was inured to the sights and sounds of artillery fire, and his cool presence in the redoubt that morning kept the American fighting men from surrendering to sheer unreasoning panic.

During the Lively’s cannonade, Prescott kept his men low and under cover, but as soon as the firing stopped the veteran colonel acted without hesitation. Correctly adjudging the redoubt’s right flank as the lesser concern, he immediately set the men to work on shoring up the exposed left flank. He laid out a line that extended approximately 165 feet from the redoubt, running from the crest of Breed’s Hill, anchoring in a swamp at the hill’s base.

Somehow his boys summoned up the strength and the will to pick up their tools again, to hack at the unyielding soil. Daylight made the task easier, but fatigue made it harder. Enervated muscles protested at every swing of a mattock; joints cried out in pain every time a shovel blade struck rock with a jarring ring. The men were on the cusp of physical collapse. Only desperation—and Colonel Prescott—drove them on, and at a fevered pace.

As they dug the deep trench, Prescott’s men cast nervous glances behind them and seaward. Behind them they hoped to find relief or reinforcements, but they saw none. Looking seaward, just around eight A.M., they spied something even more disheartening. The Lively had shifted position: Captain Bishop had turned the sloop around again, warping it down the channel and dropping anchor off Morton’s Point. Two more sloops had joined her—the Falcon and the Spitfire—in the channel between Boston and Charlestown. Another two, the sloop Glasgow (armed with twenty nine-pounders) and the armed transport Symmetry (with eighteen nine-pounders), had worked their way well up the Charles so they could rake Charlestown Neck with artillery fire. It was not an ideal point for such a task; a milldam kept the ships some distance from the Charles River shore. Hovering nearby were several small “gondolas” or scows radeaux, small gunboats each armed with one twelve-pounder.

The ships surrounding the peninsula were but yapping pups when compared to the big third-raters like the Somerset and the Boyne. The Spitfire’s main armament of six three-pounders was laughably puny for this sort of work. To the Americans looking down at the smaller craft from Breed’s Hill, though, it seemed as if half the king’s navy was ranged against them . . . eight men-of-war, Peter Brown claimed to see, but given the circumstances, Brown can be forgiven a little hysterical exaggeration. Standing out in the open as they dug the new trench line—the “breastwork,” as it came to be known—the Americans on Breed’s felt horribly unprotected.

Then it began all over again: the flash, the shuddering boom, the thud of solid shot hitting packed earth, only this time it came from several ships and several directions at once. The big twenty-fours of the Copp’s Hill battery joined in about an hour later. The former Admiral’s Battery was much stronger now; during the morning, British soldiers had dragged three more twenty-fours and a large siege mortar up to the battery. Copp’s was too distant for the guns to have much effect on the redoubt or the breastwork, or to have much chance of hitting the men, but still the cannonade worked its dark magic.