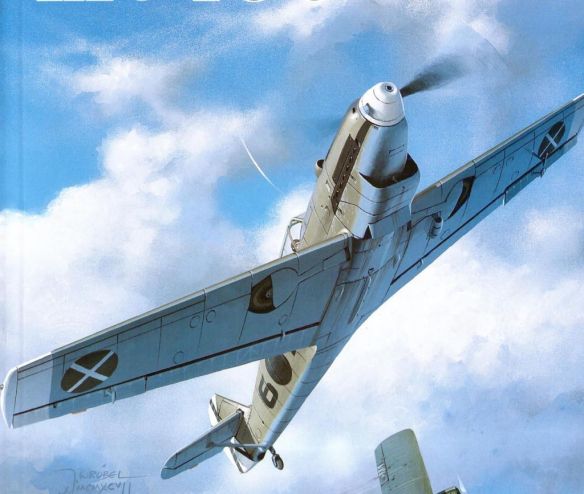

Messerschmitt Bf 109 B in Spain.

Messerschmitt’s fortunes changed dramatically when he sold one of his trim-looking M.23 racing monoplanes to Hitler’s favorite deputy, Rudolph Hess. Money was soon made available to restructure BFW as a going firm, but Milch frustrated Messerschmitt’s hopes by consigning the Augsburg works to building Heinkel’s He.45 reconnaissance planes. And even in this Messerschmitt faced a ridiculous situation: Heinkel liked Messerschmitt as little as did Milch, and when BFW technicians appeared at Warnemünde to inspect the aircraft they were to manufacture, Heinkel refused them entrance to the factory. The absurd stalemate was sorted out, but Messerschmitt was not a man content with realizing other men’s designs; he found buyers in Rumania for a new airliner and set to work. It was at this juncture that the Luftwaffe’s Technical Office, in the form of Wilhelm Wimmer, offered Messerschmitt a clear shot at the German fighter competition.

The odds against him were considered high because, of the twenty-four different designs Messerschmitt had created, only one had been militarily oriented, and that one a lusterless stab at a biplane bomber back in 1928. But both Wimmer and Hess, an avid amateur pilot, knew that Messerschmitt had a new thoroughbred in stable, the finest plane of its kind in Europe, and little imagination was required to visualize its quick evolution into the kind of fighter the Luftwaffe needed. The design in question, a four-place, low-wing, all-metal craft — the first Messerschmitt had ever built — known as the Bf.108, had been created to satisfy the need for a light, high-speed touring plane, and, more specifically, to equip German teams competing in the annual European Challenge de Tourism Internationale. Although power was limited to 220 horsepower, the 108’s exceptionally clean lines and light weight provided a speed of just under 200 miles per hour and a range of just over 600 miles. Independently operating Handley-Page slats mounted on the outer portion of the wing leading edges provided adventuresome pilots with unprecedented control at low speeds and at unusual flight attitudes. With, for instance, the nose up and the wings vertically banked, the slats popped outward (at from 63 to 68 miles per hour) to impart lift, retarding stall until the last moment — and giving the pilot advance warning before the craft stalled absolutely. The 108 had a roll rate of sixty-four degrees per second and was vigorously acrobatic.

Using the tourer as a design base, Messerschmitt and his designers created a slimmer, more angular version with a narrow cockpit for one man, a shorter wing and fuselage, and room in the nose for guns. Engineers mounted the British Kestrel V engine, the Bf.109 was test flown in September 1935, and three weeks later, Messerschmitt pronounced it ready for competition.

Designer Kurt Tank’s Focke-Wulf 159 high-wing monoplane was the most beautiful plane entered in the final trials at Travemünde. It was about twenty years ahead of its time in light-plane design, but it was not a fighter. Eliminated. The handsome, gull-winged Arado 80 looked promising, but the mandatory fixed gear produced excess drag with a consequent loss in required speed. Eliminated. This left the Bf.109 and Heinkel’s entry, the He.112, another gull-wing, low-wing monoplane with retractable gear and the only open cockpit among the four entrants — a concession to those World War I pilots in the Luftwaffe high command who did not believe a fighter pilot could see unless his head was exposed to the blast of propwash. Heinkel’s problem with the 112 stemmed from his design chief, Heinrich Hertel, an inveterate tinkerer cursed with the typical German industrial disease of overengineering. Is the airframe strong enough here? Better add another brace and some more rivets. This former does not look right. Tear it out, strengthen it, replace it. The oleo struts for the gear are too long. Take them out, shorten by seven centimeters, and put them back. But this means the wheel wells in the wings will have to be moved inboard. We’d better …

The result was a heavy fighter made up of 2,885 individual parts, and no fewer than 26,864 rivets. In his obsession for last-minute alterations, Hertel had no time left over to install mechanically operated hydraulic retraction gear, and the Luftwaffe engineer who carried out the test wore a blister on his hand cranking the gear up manually. Heinkel watched as the engineer “climbed out of the machine covered with sweat and cursing roundly.”

The test pilot who flew the 109 reported that the plane was fast and responsive in the air, but ill-mannered on the ground. To lessen the strain on the wings and to avoid clutter between the ribs, Messerschmitt had the gear struts attached to the fuselage instead, which resulted in splaying out the wheels and reducing the track. This made ground handling tricky, and when the 109 was on takeoff roll, it exhibited a maddening tendency to swerve abruptly to the left before becoming airborne. The pilot said you had to keep pressure on right rudder at the moment the stick came back to raise the tail, otherwise ground looping was inevitable. The 112 was tighter in the turns, but at 292 miles per hour, the Messerschmitt was faster. The competition ended in a Mexican standoff, and Udet threw up his hands and ordered ten each from Heinkel and Messerschmitt for the final acceptance tests.

Heinkel’s subsequent prototypes were cleaned up aero-dynamically, equipped with automatic retraction gear, fitted with an enclosed canopy, and emerged with elliptical wings four feet shorter than the original. Powered with a different engine, the Jumo 210-D rated at 690 horsepower, the He.112V4 weighed in at 4,894 pounds loaded, but speed shot up to 317 miles per hour. Messerschmitt’s fourth prototype boasted stronger landing gear, slightly improved ground manners, and a Jumo engine that did nothing for its maximum speed. Udet flew the He.112 himself, and admitted that he liked the fighter’s superior rate of climb and sturdier gear, but the final approval was going to the competition. He explained why: the Bf.109 was already earmarked to receive the new DB 600 engine that would push it to past 340 miles per hour, its straight-line wings were easier and cheaper to manufacture, and, besides, Messerschmitt’s Augsburg plant was ready to roll in series production, while Heinkel was burdened with bomber contracts and handicapped by Heinrich Hertel’s manic production techniques. Puffing on a cigar, Udet suggested to Heinkel, “Palm your crate off on the Turks or the Japs or the Rumanians. They’ll lap it up.”

Heinkel was bitterly disappointed, and especially so because he lost the order to Messerschmitt, whom he considered an upstart as far as military aircraft were concerned. Heinkel also admitted that in “turning down the He.112, Udet had hit my deepest striving — to build the fastest possible airplane.” Heinkel was far from ready to admit defeat in the fighter field, and would resurface dramatically two years later.

The Luftwaffe was called on to play a major role in a Hitlerian gamble for high stakes when it was barely a year old, still raw with unassimilated growth, and with its supporting industries only beginning to tool up for modern weapons. On February 12, 1936, Adolf Hitler summoned to the chancellery General Werner Thomas Ludwig von Fritsch, commander in chief of the army, and told him he had decided to reoccupy the demilitarized Rhineland. General von Fritsch hesitated, saying that he agreed in principle with the Führer that the Rhineland had the greatest strategic significance in case of war with the West, but pointed out that the Wehrmacht was still in the throes of organization and was far too weak to deal with an estimated 110 divisions the French could mobilize. Hitler said he wanted the Rhineland, but he did not yet want war; the operation was to be a major bluff, probing the willingness of the Locarno Treaty signatories to back up their convictions by force of arms. General Alfred Jodi described the atmosphere prevailing inside the General Staff as “like that of the roulette table when a player stakes his fortunes on a single number.”

The operation was mounted with frantic haste. The directive for Operation Winterübung, Winter Exercise, was drawn by General von Blomberg only sixteen days after the Führer’s decision, and was not released until March 5, just forty-eight hours before the army was ordered to cross the Rhine. The Luftwaffe was alerted, and General Wever began shuffling his scattered units around like pawns on a chessboard. Two understrength fighter wings, JG 132 and JG 134, were pulled from their bases and sent south. A bomber wing, KG 4, was ordered to stand by, its unwieldy Ju.52s fuelled to the limit for a possible mission to Paris. The few fully operational tactical training schools were stripped of instructors and planes, hastily formed into impromptu squadrons, and moved to bases all up and down the Rhine. On the cold, wet dawn of March 7, three small battalions of German infantry, about three thousand men in all, armed with nothing more than rifles, carbines, and machine guns, crossed the Rhine and occupied Aachen, Saarbrucken and Tier. The helmeted men, their capes dripping with rain, were greeted with cheers by Germans who had not seen friendly troops in more than a decade. Overhead buzzed the Heinkel and Arado fighters of the Richthofen and Horst Wessel squadrons. The pilots kept glancing toward France, expecting to see massed formations of the Armée de l’Air. The German airmen were understandably apprehensive: not one fighter could give combat; those who had ammunition lacked guns, and those who had guns lacked the synchronization gear necessary for firing through the prop. If French planes appeared, they would have to be rammed.

Tension in the Reichs chancellery, in Army High Command, and inside the Air Ministry had never been so high. Hitler paced the carpet, and General von Blomberg’s aides noted that the Rubber Lion had developed a facial twitch. Luftwaffe staff officers hovered over the telephones, half expecting the next call or the next would bring word of crushing French reaction, wiping out the Rhine bridgeheads and massacring the carefully hoarded — and quite harmless — fighter aircraft. French Intelligence, usually among the world’s best, grossly miscalculated German armed strength inside the Rhineland at 265,000 troops. The British more realistically believed Hitler had sent in 35,000 men, nearly four divisions, and they erroneously accepted Hitler’s boast made a year earlier that the Luftwaffe had achieved air parity with the RAF. Reaction was not what Hitler and the others feared; the French prepared for defense by manning fully the subterranean Maginot Line and mobilizing thirteen divisions, and the British pleaded for calm. And outside of anguished cries in the Chamber of Deputies, calm indeed prevailed. Hitler had gotten away with it. Neither the British nor the French public believed that the Rhineland, characterized by Lord Lothian as “after all, Germany’s back garden,” or the principle that lay behind its occupation, was worth fighting over. Hitler later admitted to Blomberg that he “hoped he would not have to go through another such ordeal for at least ten years.”

The Luftwaffe’s rapid deployment revealed the luster and fine-toothed gearing imparted to the Air General Staff by Walther Wever during his thirty months in office. His gift of motivating men to reach for the best within themselves — to feel shame at any lesser effort — created an electric air of striving for total efficiency; nobody wanted to let Wever down. When the general planned war games in conjunction with the army, his staff performed prodigies of planning in order to make good Wever’s promises. If Colonel Heinz Guderian expected a simulated bombing attack in front of his 2nd Panzer Division at 0845 hours, he could be sure of the arrival of the JU.52S at the required time. If a corps artillery commander needed air spotters to call strikes for his new Krupp guns, he could be sure the He.45s would be buzzing over the range at the time the shoot was scheduled to begin. Wever created not only an efficient staff but, what is rarer, a harmonious one. And since Wever had originally distinguished himself in staff operations of the army, both in combat and during the difficult days of the hundred-thousand-man peacetime Reichswehr, no one in the Wehrmacht felt that he was dealing with an air specialist blind to the requirements of other branches. In recalling Wever’s crusade for a strategic strike force, one of his operations deputies, General Paul Deichmann, noted Wever’s state of mind during the first large-scale war game carried out by the Luftwaffe late in 1934.

“During the course of the war game the bomber units were employed deep in the heart of enemy territory. At that time, most of these units were equipped with provisionally armed JU.52s, which were completely inferior to the French fighters [in use at the time]. Officers in charge of the maneuver suggested to General Wever that he assume a loss of 80 per cent of the bomber force, but Wever refused brusquely with the words, That would deprive me of my confidence in strategic air operations!’ Although the maneuver leaders pointed out that the percentage of losses would presumably be that high only until the Luftwaffe had more modern bombers at its disposal, Wever insisted upon a lower percentage.”

Hitler’s Rhineland adventure directed Wever’s thoughts to the west and to the north. Although Wever remained convinced that Russia was Germany’s greatest potential enemy, he could not discount the possibility of England’s springing to the aid of France, the traditional enemy. It was all very well for Hitler to proclaim his desire for friendship with the British, but it is the function of the General Staff to base its plans for the future upon pragmatic considerations and not upon political desires, no matter how fervent. There was no question of the ability of the German naval building program, then accelerating, to provide the Reich with parity at sea with the Royal Navy. Wever believed that strategic bombers could play a decisive role not only in laying waste Britain’s industries, concentrated as they were on an island only five hundred miles in length, but in maritime operations designed to deny the British economy raw materials, and the people, food. Bombers with a radius of action of even twelve hundred miles could range from Germany far out over the North Atlantic as far as Iceland; the central Atlantic approaches to the ports of France could be covered and so, too, could the entire Mediterranean, almost as far as Suez. With the medium bombers and the Stukas and the chosen German fighter now coming off the production lines, Wever pressed for completion of strategic bomber planning.

The Ju.89 prototype rolled out for flight tests. The wings spanned an inch under 115 feet, and the deep-bellied fuselage could hold 2,600 pounds of bombs. The great drawback of the Ju.89 was of power; the only engines available were 620- horsepower Jumos, enough only for a maximum range of 1,240 miles and a top speed of 192 miles per hour. The Do.19, harnessed to the same power plants, was 15 miles per hour slower, but had a range of 1,800 miles — still not enough for the demands Wever intended to impose later on. Wever had not expected greater performance figures for either bomber, and believing that in the next air war God would be on the side of the greatest horsepower, ordered further testing to be carried out, pending availability of newer, more powerful engines. He was not to live long enough to see his dream realized.

Although Wever’s rank entitled him to a courier plane with stand-by crew, he insisted on piloting his own flights to various corners of Germany. He had less than two hundred hours in his logbook, but chose the fastest plane of its type for his personal aircraft, the single-engine, three-ton He.70 Blitz. On June 3, 1936, Wever and his flight engineer climbed into the Blitz and flew from Berlin to Dresden, where Wever was scheduled to give a talk to the cadets at the new Air War Academy. Wever finished his business at the Luftkriegsakademie, then ordered his driver to hurry him back to the airfield; he was due back in Berlin to attend the funeral of General Karl von Litzman, hero of the war on the Eastern Front in 1914, and Wever was never known to be late. Wever slipped his flight suit on over his dress uniform and looked around for his flight engineer. Where had he gone to? Wever guessed he had gone into Dresden on some errand. He paced the tarmac, shooting glances at his watch, impatient to be off. His mind on the 105-mile flight back to Berlin, Wever failed to make the customary walk-around preflight check of the He.70, an airplane he had only recently acquired and with whose eccentricities he was not thoroughly familiar.

Finally the flight engineer hurried across the runway, apologized for the delay, and without further ado the two men got back into the airplane, strapped in, and started the engine. Observers on the ground watched the Heinkel move down the concrete strip, gathering speed. The tail lifted, then the wheels left the runway and Wever got the nose up in takeoff attitude. One wing dipped slightly, and instead of being picked up with a quick movement of the ailerons, the wing dropped lower still, lost its grip on the air, and the heavy He.70 plunged into the ground with the engine running full bore at takeoff rpm. The Blitz, heavy with fuel, exploded on impact, killing Wever and his tardy flight engineer instantly. Enough of the wreckage was left to determine the cause of the crash: failure to disengage the aileron lock prior to takeoff, a matter of a simple hand movement.

According to the Luftwaffe intelligence chief, Major Josef “Beppo” Schmid, who was in the Air Ministry in Berlin when the news was telephoned through, Goering “broke down and wept like a child.”

And well he might have: with Wever were buried the Luftwaffe’s chances of winning a war spread beyond the narrow frontiers of continental Europe.