When the war ended, Udet was twenty-two and unemployable. His only trade was combat flying, his only reward the Blue Max, his only yearning, the sky, and freedom, his only need. He turned down a posting with the Reichswehr, married his wartime girl, Zo Link, and borrowed money to start a small aircraft factory. He built and demonstrated neat biplane sport planes with such evocative names as Hummingbird and Flamingo. His marriage dissolved, then his interest in manufacturing. His partners wanted to move into the four-engine airliner business, and big planes interested Udet not at all. He was a born Bohemian, blessed with wit and a knack for mimicry and caricature with pen and ink. Udet was sociable without being social, and expansive without being garrulous. Parties in his Berlin flat were famous in a time when every kind of behavioral barrier had been let down, and chance callers were always assured of a glass of champagne or brandy, or the two mixed together served in a shell case, the famous concoction dreamed up by a Lafayette Escadrille pilot and known as a Seventy-five. Udet was a drinker without being a drunk, and a raconteur who was never a bore.

Udet, second only to Manfred von Richthofen on the victory list, could have bartered his name and his personality on the marketplace; but Udet was neither politician nor prostitute. He was a pilot, a technological man of his times needing to use his craft — a narrow skill at best — to pay his way in life. Like most bon vivants, Udet was at heart a realist, sensing that heroism in war does not necessarily qualify a man to administer the affairs of commerce. He would not sell his name for promotion, but when approached by twenty-six-year-old Leni Riefenstal, painter and ballerina turned actress and film director, to put his courage and piloting skill to hire in film work, Udet accepted readily. He worked both in Africa and in the Arctic, where his best-known footage was shot for the 1929 feature, The White Hell of Pitz Palü.

Udet, barnstorming in the United States, made friends wherever he went, including wartime air service pilots he had dueled with over the western front more than a decade earlier; among them were Eddie Rickenbacker and Elliott White Springs. Thousands of Americans thrilled to Udet’s seemingly harebrained stunt flying, and only pilots in the crowd realized that what laymen took for madness was but consummate skill pushed to the limit by personal courage.

Among Udet’s admirers was the American pioneer airman, Glenn L. Curtiss, who invited the German to visit the Curtiss-Wright plant in Buffalo, New York, while Udet was touring America in 1933. On September 27, a date that would have fateful repercussions for the Luftwaffe, Curtiss asked Udet if he would like to fly a factory-fresh F2C Hawk, a robust single-seat biplane designed for the U.S. Navy as a carrier-borne dive-bomber. Twenty minutes later Udet and the Hawk were wringing each other out, man versus machine in a brutal contest to see which would come apart first under the punishing G-loads imparted to both frames as Udet hurled the plane at the ground again and again, hauling the stick back sharply against his stomach only seconds before the earth rushed up to claim them. When Udet landed and taxied up to the hangars he was drained and thrilled. Aiming the nose of the plane at one of Curtiss’s factory buildings and howling down at over 250 miles per hour was like riding a shell on its downward plunge to the target. Here was a plane to thrill the crowds and, it occurred to Udet, one with which the German air arm should experiment. Few targets are harder to hit from the air than ships underway on the open ocean, and if the U.S. Navy was working on the idea of the dive-bomber as the solution to the problem, then so should his own people in Berlin. Udet immediately wrote Erhard Milch with a glowing description of the Curtiss Hawk, wondering if there were some way he could bring a pair of them back to Germany. Milch wired back agreement, adding that funds to cover purchase cost were on the way. Curtiss, happy to make the sale at a time of depressed markets at home, received no problem with export licenses from the U.S. government.

Two months later, Udet was at the Rechlin test center with the assembled American Hawks. Gathered on the field whipped by cold December winds, Milch, Goering and others from the Air Ministry watched Udet scream down on them in four successive power dives, pulling out a little closer to the ground each time. Through the fog of near blackout, Udet rolled off the top of the zoom and treated the fighter pilots among the critics below to an exhibition of acrobatics, proving that the thirty-seven-year-old pilot and the new machine could take it. Udet was invited to a conference in Berlin at the beginning of the new year, the only civilian among the galaxy of brass, and the upshot was an order from Goering to develop some kind of vertical bomber. Wever, as chief of staff, was a supporter of the idea because it did not interfere with his ideas of a mixed force: the strategic bombers then being developed by Dornier and Junkers, the medium Do.17s and the He.111s then in the planning stage, and now the Sturzkampfflugzeug — literally, the plunge-battle aircraft. It was not envisioned that the Stuka would be used primarily as a naval attack weapon, but rather as a kind of extreme-range piece of heavy artillery. None of the German bombsights then under development, the Goerz-Visier 219 or the Lofte 7 and 7D, were considered sophisticated enough to achieve acceptable accuracy in horizontal bombing except by the most experienced crews; Stukas, with their inherent accuracy, would solve the problem of putting bombs on small targets in the field: bridges, power stations, fuel and ammo dumps, roads, tanks, enemy airfields. Moreover, Germany’s raw-material reserves were limited and production of Stuka-type aircraft would eat into these strategic reserves sparingly.

The most outspoken opponent of the dive-bomber concept was Major Wolfram von Richthofen, thirty-eight, Manfred’s younger cousin. Wolfram flew his first patrol on the day that Manfred flew his last, and finished the war in 1918 with eight kills. A tall, heavy man with a porcine face and narrow eyes, he based his objections to the Stuka on his wartime experiences as a fighter pilot and upon his studies for a doctorate in engineering after the war. Richthofen believed that it was suicidal for aircraft to operate below three thousand feet in the face of ground fire, and jettisoning a bomb load vertically any higher would nullify the pinpoint accuracy claimed for dive-bombers. Nor did he believe that aircraft could be built that would withstand the cumulative effects of stress absorbed by airframes in day-in, day-out operations. On July 20, 1934, a near disaster at Berlin’s Templehof field seemed to prove his theory correct. Udet had been practicing during the spring and early summer, and was no doubt the most proficient dive-bomber pilot in the world by the time July rolled around. With almost the entire Luftwaffe General Staff watching, Udet rolled the Hawk on its back and plunged for the earth. He hauled the stick back at the last moment, the Hawk began its agonizing pullout — then the tail section fluttered wildly, finally wrenching loose. The Curtiss plummeted straight down, engine running full out. Udet, who had been through all this before, unstrapped and went over the side, hauling on the D-ring as he went. The chute popped just before he slammed into the ground. The Hawk exploded at the far end of the field.

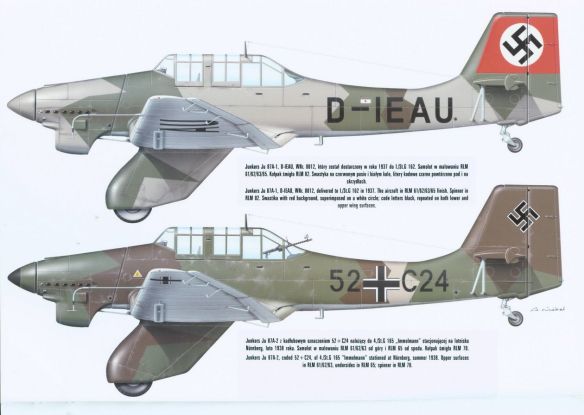

Despite the disintegration of Udet’s plane, the Luftwaffe high command was convinced of the practicality of the Stuka idea, and development orders went out to Arado, Blohm und Voss, Heinkel, and Junkers. To Junkers’s chief designer, Wilhelm Pohlmann, the order seemed almost coincidental; already sketched out on his drawing board was a study for an advanced, all-metal, low-wing dive-bomber based on the K.47 that had been built in Sweden and tested at Lipetsk. The Luftwaffe specified dive brakes, and while templates were being cut for the new plane, brakes were fabricated and fitted to the K.47 and given a thorough testing. The K.47’s twin-ruddered tail offered the gunner a wide field of fire to the rear, and so the twin tail was retained on the new prototye. Fitted with a 600- horsepower Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine, the prototype Stuka, the JU.87V-1 was rolled out of the assembly hangar at Dessau in the early spring of 1935, ready for flight. The Ju.87 was square, angular, awkward, and unwieldy looking — in fact, it was ugly; but it looked strong. Test pilots felt few qualms about putting it through its paces, gradually increasing the steepness of the dive and the G-levels as flight testing progressed. What were its limits? Nobody knew. Determined to find out, one pilot pushed the Ju.87 Past the limits of endurance, and although the wings held, the twin tail tore loose before pullout and the Stuka exploded against the ground. A standard rudder was fitted to the next prototypes, as well as an automatic pullout device connected to the elevators and actuated by the altimeter; blackout at five and six Gs, caused by gravity’s draining of the blood from the brain down to (it seemed) the pilot’s boots, was not to be taken lightly in an airplane at speed close to the ground.

While Junkers was busy pinching out the bugs in the Ju.87 and the others were working hard to catch up, Udet was being drawn into the Luftwaffe’s web. Milch, Wever, and the Luftwaffe’s personnel chief, Hans-Jürgen Stumpff, decided that Udet’s passion for flight was needed more in a rearming Germany than at air shows. He was offered the rank of colonel and a post as inspector of the fighter and dive-bomber forces. Udet hesitated; throwing away his personal freedom after seventeen years was something he must think about. Besides, he was all but oblivious to the precepts of National Socialism, and the Luftwaffe was being bent strongly along those lines. Udet was no political animal, and he admitted it. What would the Führer say? In point of fact, the matter had been cleared all the way up to Hitler, whose admiration for Udet’s record far outweighed his objection to placing politically unoriented officers in key positions. Udet was won over with a simple, clear and honest argument: if he wanted to see Germany equipped with the finest dive-bombers in the world, he could not do so as a civilian — but with the rank and the title offered, nobody could oversee the job better. On June 1, 1935, Ernst Udet was sworn in.

A Berlin tailor outfitted his now portly figure in a new Luftwaffe uniform, in which he appeared only infrequently at his office; paperwork was not for Udet. Most of his hours were spent in the cockpit of his private staff plane, a little Siebel Beetle, rushing from one aircraft factory to another, urging speed in the dive-bomber developmental program. Early in 1936, the Luftwaffe was notified by the four prime contractors that each was ready for the trials to be staged at Rechlin.

Arado missed the boat by submitting a biplane design, and the Ar.81 looked, and was, obsolescent from the beginning. Designers at Blohm und Voss had apparently not read the Luftwaffe specifications, for their Ha.137, a low-wing monoplane, was a single seater, and the Technical Office had distinctly called for a two-place aircraft. Heinkel took off on his already successful He.70 design and fielded the He.118, a slick-looking metal monoplane with retractable gear and powered by the DB 600 engine of 900 horsepower, giving it a top speed of more than 250 miles per hour. It looked to be a sure winner. Then the worked-over Ju.87, the fourth prototype, was unbuttoned for inspection. The Junkers Jumo 210 engine was fitted with a three-bladed, controllable-pitch prop designed by the American firm of Hamilton-Standard and built under license in Germany. The elongated greenhouse provided almost unrestricted visibility for the pilot and rear gunner. The oversize wheels were covered with huge metal spats. The ugly square tail was heavily braced. A heavy crutchlike strut was fastened flat underneath the belly; just before bomb release, the pilot actuated the crutch, which swung down and out so that the falling bomb would clear the arc of the propeller blades. Inboard of each wheel spat was a small round housing with fanlike blades. One of the inspecting officers asked Udet, “What’s that?” Udet said, “You’ll see!”

The flights of the Arado and the Blohm und Voss were quickly dispensed with. Then the Junkers test crew got aboard, were quickly airborne, and began diving. To the shattering roar of the Jumo engine and the three-bladed prop was added an unearthly scream, boring into the eardrums with almost unbearable intensity. The Ju.87 pulled out of its dive so close to the field the watchers instinctively ducked. Again and again Rechlin vibrated to the banshee wail of the assaulting Stuka. When the Ju.87 wheeled around to shoot its landing, only Udet and the Junkers engineers were smiling: what Udet had done on one of his many trips to Dessau was to suggest attaching sirens to the underside of the Ju.87 as an experiment in psychological warfare. He called them “trumpets of Jericho,” and they had had their effect.

It was a tough act for the sleek He.118 to follow. Unknown to Ernst Heinkel, the new test pilot named Heinrich had an aversion to power dives, although he was reliable in every other way. The He.118 took off, reached altitude, then tentatively dropped its nose toward the ground. Heinrich swept gracefully down in gentle swoops, his flight parabola resembling that of a glider with a throttled-down engine. Dive he would not, and the trials at Rechlin ended with the Ju.87 as the obvious choice. Heinkel unleashed his Swabian temper on his test pilot, but cooled down when Udet walked over and said, “Heinkel, I won’t make up my mind at the moment. I must dive your damned plane myself. I’ll come out to Marienehe.”

Udet showed up unexpectedly at Marienehe some weeks later on a day when Heinkel was busy giving the red-carpet treatment to an American visitor, Charles Augustus Lindbergh. Milch had rung through from Berlin, telling Heinkel “to show Lindbergh everything.” In halting English, Heinkel answered the Lone Eagle’s penetrating technical questions about all of the plant’s latest designs. Lindbergh had already toured the other German aviation factories, and it struck Heinkel that the American flyer “knew more about the Luftwaffe than anyone in the world.” While they were inspecting the third-floor workshops, Udet was aloft preparing to put the He.118 through its paces. Heinkel and Lindbergh missed witnessing what happened next.

Udet hauled the light bomber up to ten thousand feet in the clear blue early summer sky and unhesitatingly rammed the stick forward. The goo-horsepower engine wound up tight, and Udet’s ears were pierced with a high-frequency scream. Too high. Udet, forgetful of Heinkel’s warning, had neglected to check the pitch setting on the controllable prop. The He.118 bucked and vibrated, plunging straight for the deck out of control. Udet fought to get his bulky frame clear of the cramped cockpit. He got half out, battered by the slipstream, but one foot was wedged against the rudder pedal and the airframe. The prop wound up past its limits and flew off into space. The tail assembly tore loose and fluttered away through space. Udet wrenched his socked foot from the jammed oxford and flew backwards out of the cockpit. His chute cracked open while his body was moving downward at more than 200 miles per hour, and he crashed heavily against the earth in a cornfield. Unconscious, Udet did not hear the explosion as the He.118 tore itself to pieces not far away.

Udet, bruised and sore but otherwise uninjured, spent a few days in a Rostock hospital, managing to stay pleasantly tight on champagne smuggled in by friends. Heinkel’s hopes for the He.118 were buried in the wreckage of prototype, branded by Udet as no more than “a damned deathtrap.” The contract for the Stuka was let to Junkers, and shortly afterward, the first of nearly five thousand production models began rolling off the lines at Dessau.

On the day following Lindbergh’s visit to Marienehe, a formal reception was held in the U.S. Embassy in Berlin for the American pioneer aviator who, if he held second place at all in the affections of an air-minded public at home, ranked next to Eddie Rickenbacker. Almost every Luftwaffe pilot and command officer of note was present, and so were the leading designers. The American military attaché, Truman Smith, hoped Lindbergh would not make a pacifistic speech, for the state of the world deeply troubled Lindbergh, and what he had seen of the Luftwaffe impressed and disturbed him. Goering, as usual, turned up late for the reception, and breezily handed Lindbergh a small leather case holding a decoration. “From the Führer!” boomed Goering. Ernst Heinkel, standing nearby, observed that “Lindbergh looked mockingly at Goering, shook his head, and put the decoration in his pocket without bothering to look at it.”

Lindbergh made no embarrassing speeches, but before he left Berlin he did field a prophecy. He said to Heinkel, “It must never come to an air war between Germany, England, and America. Only the Russians would profit by it.”

The era of the biplane fighter was ending even while He.51s and improved Arado 68s were coming out of the factories in fulfillment of the quotas established under the Rhineland Program. In the summer of 1934, the Air Ministry invited tenders from the aviation industry for a new fighter, specifying that the speed required must be no less than 280 miles per hour. This would require adroit approaches to aerodynamics and the keenest scrutiny to every weight-saving trick known to the engineers; at the time the various designers bent over their boards to begin initial design studies, there was no engine available for the competition that exceeded 700 horsepower. Two of the manufacturers were handicapped from the start. Arado was told their entry could assume any configuration the designers could dream up — but they could not submit a plane with a retractable undercarriage, which was not yet considered foolproof. Focke-Wulf at Bremen was instructed to produce a high-wing monoplane based on its successful FW.56. Heinkel was told he could build what he liked, and so was the newcomer, Willy Messerschmitt, of the Bayerischeflugzeugwerke at Augsburg. BFW was given free rein because Messerschmitt was considered to stand little chance, and those in the know inside the Air Ministry considered it astounding that the tall, scowling, heavy-jawed, ruthless-looking builder should be a contender at all. Messerschmitt and Milch had disliked each other on sight, and during the years Milch was running Lufthansa, Messerschmitt succeeded in selling the airlines very few passenger craft, Messerschmitt’s entire stock in trade. In 1935, Messerschmitt was thirty-seven and had been involved with aviation design for twenty years. Messerschmitt and his mentor, Friedrich Harth, built and flew a glider in 1916 that stayed aloft for two and a half minutes, and after the war the team was a familiar sight on the Wasserküppe. Between 1925 and 1928, Messerschmitt built a number of light airliners, biplanes, and sport machines, but it was in the summer of 1928 that he made his move to enter the ranks of major German industrialists. As the son of a Frankfurt wine merchant, he had no resources of his own, but as the son-in-law of the wealthy Strohmeyer-Raulino family, he was able to secure backing to buy the shares of the BFW company owned by the Bavarian government. The company failed in 1931, but Messerschmitt saved it by selling personal possessions and lining up contracts with a Rumanian firm to build his designs under license.