With all of Germany humming after twelve years’ stagnation, the Rhineland Program moved swiftly toward completion. By the end of 1934, with another nine months in hand, approximately half of the four thousand planes ordered by Milch had emerged from the factories and were delivered to the proliferating units activated by Wever. There were forty-one organized formations scattered throughout six Luftkreis (air district) commands, units whose military functions were concealed under innocuous code names. The bomber unit equipped with Dornier 11s at Fassberg, for example, was camouflaged under the name Hanseatic Flying School. The bomber training station at Lechfeld operated its Ju.52s undercover as research planes of the headquarters, German Flight Weather Services. The familiar German Commercial Pilots’ School at Braunschweig hid the activities of the Heinkel 46 reconnaissance outfit. And at Prenzlau, student bomber pilots took refuge as crop dusters, their JU.52s merging with the State Agricultural Pest Control Unit.

The first fighter unit was activated on April 1, 1934; it was known unofficially as Squadron 132, but officially as one of the so-called advertising squadrons that had been parading across German skies for more than a year. The unit designation, 132, was not meant to imply that Germany possessed a hundred-plus squadrons, but was a simplified code; the first digit indicated that the unit was squadron one, the second revealed that it was equipped with fighters, while the third digit showed that the squadron was based within Air District II (Berlin.) Chosen to command was Major Robert Ritter von Greim, a grizzled veteran of the skies over the Western Front, a dead shot with twenty-five kills to his credit, a wearer of the cross of the Pour le Mérite, and, until his return to Germany, one of the organizers of Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese air force.

To meet the immediate needs of the expanding air units for men to perform the less glamorous chores of air base duty, thousands of NCOs and enlisted men were summarily transferred from the Reichswehr and put into new blue uniforms as they became available. Because most of them were volunteers, and because of Seeckt’s policy of quality when he could not have quantity, the airmen, almost without exception, were of high caliber and well qualified to learn quickly the technical aspects of their new career field. It was after August 1,1934, that incoming airmen were presented with a new oath to swear, an oath far more personal than existed during the Weimar period. On that date, President von Hindenburg died and Hitler assumed his title as well as that of chancellor. Instead of swearing loyalty to the Constitution, recruits henceforth chanted, “I swear by God this holy oath, that I will render to Adolf Hitler, Leader of the German nation and people, Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, unconditional obedience, and I am ready as a brave soldier to risk my life at any time for this oath.”

The Nazi Party was not mentioned, but soon its symbol began to appear on every naval and military uniform. General von Blomberg, although adamant against allowing Wehrmacht members to join the NSDAP, nonetheless wanted to show his commander in chief that the Wehrmacht was as loyal to him as were the SS and other purely party organizations. He ordered new cloth badges from the quartermaster, a design featuring a straight-winged eagle clutching a small swastika in its claws. These were sewn on the uniform jacket just over the right upper pocket. Goering ordered badges with more sweeping lines, a soaring eagle looking downward, talons clutching the party symbol as though a bird of prey was dragging its victim through the sky. The order was placed in anticipation of the Führer’s next big moves, which were not long in coming.

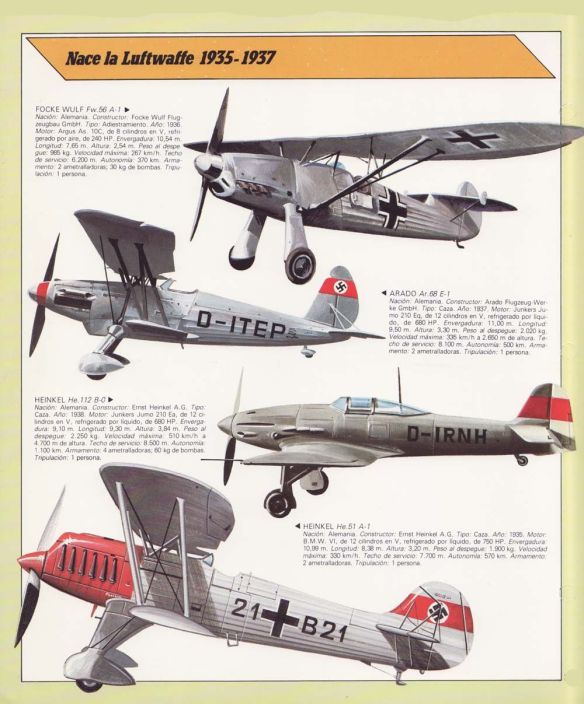

On February 26,1936, Adolf Hitler signed a decree that established the air force as an independent branch of the armed forces. At last, the shadowy air arm had a name given it by the Führer himself — the Reichsluftwaffe. Nobody liked it, and in general parlance the name was shortened to Luftwaffe (air weapon), which soon became accepted official usage. The new command structure ranked the Luftwaffe equally with the army (Reichsheer) and the navy (Reichsmarine), answerable through Goering to Blomberg and through him to Hitler. On March 1, the decree was implemented. Independence! A dream British military airmen had realized in 1918 after three years of hard political infighting, and a dream their American counterparts had despaired of achieving, and would not realize for another twelve years. On March 10, Goering summoned the correspondent of the friendly London Daily Mail and presented Ward Price with the scoop of the year. Goering told Price he had created a new German air force, but with no intention of threatening the rest of the world; his Luftwaffe, Goering said, was purely defensive. Four days later, Major von Greim’s J.G.132 was christened J.G. Richthofen 2, and squadron mechanics got busy painting the cowlings red and adding black crosses to wings and fuselages of the new Arado 65 and Heinkel 51 biplane fighters. Roaring over German towns in warpaint, the slender, elegant Heinkels looked menacing and businesslike — and from the ground the carefully kept secret that the resurrected Richthofen Circus had no guns could not be discovered. Shortly afterward, yet another fighter wing was created out of the equipment pouring from the factories. The party influence was clearly revealed in the choice of names for J.G.134, known as Jagdgeschwader Horst Wessel For those officers and men who believed the official version of Wessel’s death in February 1930 — that he “died on the barricades in the struggle against Bolshevism” — the name was acceptable, even though Wessel had never been connected with flying in any way. To those who knew the truth, it was something else. Wessel, in fact, was a twenty-three-year-old storm trooper living in a Berlin slum, earning pocket money as a part-time pimp. He was shot to death by another party member, also a pimp, over possession of the chattel, Erna Jänicke.

When Goering made his announcement, the Luftwaffe strength stood at sixteen squadrons; by August 1, five months later, the figure had trebled, and the first-line strength stood at 1,833 aircraft, broken down as follows:

372 bombers (Do.11 and Do.23)

450 auxiliary bombers (Ju.52)

51 dive-bomber trainers (He.50)

251 fighters (Ar.64, Ar.65, He.51)

320 reconnaissance (long-range He.45)

270 reconnaissance (short-range He.46)

119 naval (He.38, Do.16, He.59, Do.18, He.51W)

There was more. On Saturday, March 16, Hitler announced that he had signed a decree reintroducing compulsory military service; conscription would enable the army to field thirty-six divisions, about five hundred thousand troops. On top of the news of the Luftwaffe as a force in being, this latest pronouncement torpedoed the already foundering ship of Versailles, leaking violations at every seam. Reaction to this German truculence on the part of the treaty signatories was pitiful: Great Britain, France, and Italy met at Stresa, under a League of Nations mandate, and spent their time concocting notes of pious outrage and condemnation. France signed a mutual-assistance pact with Russia; Russia signed one with Czechoslovakia; England kept quiet about her own plans for a treaty with Germany that would allow the potential enemy to greatly increase the Reichsmarine — an agreement reached only two months later, and one that included the British approval of German submarine building. Sir John Simon, Whitehall’s new foreign minister, was received by Adolf Hitler in the Reichs Chancellery in Berlin and listened while Hitler, now gracious, now scowling, stressed his desire for peace. Then came the sword thrust. The Luftwaffe, said Hitler, with the surety of a poker player holding a full house, has achieved parity in the air with England. This was not true at the time, but with Berlin’s streets filled with columns of marching men in brand-new blue uniforms, and with the skies overhead alive with the thunder of Luftwaffe formations of bombers and fighters, there was no way to disprove it.

Generalleutnant Wever, as he now was, having seen the Rhineland Program heading toward completion, bent his energies to the Luftwaffe’s second-generation force. Wever assigned highest priority to the development of a basic four-engine strategic bomber design. Through the technical chief, Colonel Wimmer, General Wever pressed development contracts on the Junkers works at Dessau and on Claudius Dornier at his Friedrichshaven plant on Lake Constance. Both Wever and Wimmer were satisfied with the preliminary drawings, and work proceeded to the mock-up stage. In final configuration, both bombers were remarkably similar: broad wings exceeding one hundred feet in length, four engines grouped closely together, deep-bellied fuselages, twin rudders. The Do.19, typically Dornier, was cleaner of line than its competitor, the Ju.89, which (typically Junkers) was brutish and robust. Both featured retractable landing gear housed inside the inboard engine nacelles; both bombers’ noses rode high off the ground.

Wimmer recalled how, in the spring of 1935, he persuaded Goering to accompany him on a visit to Dessau. They marched through the crowded Junkers workshops, shouting to be heard above the crash of hammers, the whine of plane saws, the stutter of riveting guns and the crackle of arc welding equipment. They passed through the great sliding doors leading into a cavernous building where the only sounds were the gentle scraping of sandpaper, the desultory slap-slap-slap of paintbrushes, and the creak of wood being fitted to wood. Goering gazed upward at the full-scale mock-up of the giant Ju.89, its bulk seeming to fill the hangar. Goering turned incredulously to Wimmer and, still shouting, yelled out, “What on earth’s that?”

Wimmer explained that it was the final wooden study of the much-discussed Ural bomber, about which the Minister must surely have been informed. Wimmer remembered that Goering turned suddenly furious and bellowed, “Any such major project as that can only be decided by me personally!” Then Goering stamped out of the building. Wimmer was at a loss, but decided that Goering’s blast was only another temper tantrum, probably forgotten by the time he got back to Berlin. Work on the Ju.89 continued.

Next, Wimmer escorted Blomberg through the Dornier works and explained in detail about the hoped-for capability of the Do.19. The War Minister listened patiently, then asked Wimmer when he thought the Do.19 could become operational. Wimmer replied, “In about four or five years.” Blomberg, along with every other German officer of field rank, believed that the next war could not possibly begin before 1942 or 1943. Therefore, if the strategic bombers, the Ju.89s and/or the Do.19s, were ready for combat by the spring of 1939 or 1940, that would be soon enough. His somewhat abstract comment to Colonel Wimmer in response to the time lag Wimmer mentioned, “Yes, that’s about the size of it,” was interpreted to mean that he was favorably impressed with the Do.19. Work on the big bomber was ordered to proceed.

The dual-purpose Luftwaffe envisioned by Wever required not only a strike force with extended reach, but a tactical sword whose importance lay not in the weight of the blade but in the speed of the stroke. Even before Wever’s installation in the command structure, airmen in the old Fliegerzentrale used to theorize endlessly about the kind of bombers they would someday build. What emerged from these serious daydreams was the concept of bombers so fast they would outrun fighters, obviating the need for heavy defensive armament whose weight — plus that of the men needed to serve the guns — could be better utilized in payload or fuel. It was a concept with which Wever did not argue. Fortunately for the development section of the Luftwaffe’s Technical Office, such a bomber already existed in prototype, a reject found in Lufthansa’s passenger-plane bin.

Late in 1933, Lufthansa presented Dornier with a requirement for a new mail plane capable of hauling six passengers; because the airlines wanted the plane for use on express runs between European cities only, range was not important, but speed was paramount. The most powerful engines then available were BMW Vis, twelve-cylinder, liquid-cooled inlines developing 660 horsepower at takeoff, and around this power plant, with its low frontal area, Dornier designers planned to build the most aerodynamically advanced aircraft in the world. The fuselage was as slim as a pencil, the nose shaped like a bullet. The round-tipped wings, fifty-nine feet long, were set in the shoulder of the fuselage, some distance aft of the flight deck, and faired so smoothly that the wing-body structure seemed to have been poured molten into a mold and allowed to set. The rudder was small and nearly triangular. The wide-track landing gear folded neatly backward into the curve of the engine nacelles, and, as a final triumph over drag, even the small tail wheel retracted into the fuselage where it was so narrow a large man could encircle it with both arms.

Lufthansa took delivery of three prototype Do.17s for evaluation. Test pilots were enthusiastic about control response and general handling, the traffic chiefs agreed that the two hundred-plus miles per hour exceeded performance requirements, and Lufthansa’s flight engineers were keen on the new power plants. But those responsible for passenger ticket sales vetoed the Do.17 on the spot. Because the plane had been designed for speed, and only speed, accommodation for fare-paying passengers was only an afterthought: a tiny cabin for two people was fitted immediately behind the flight deck, making the clients almost part of the crew; but unlike the crew, their visibility was extremely restricted. Room for four others was made just aft of the wing, providing a good view downward — along with the full benefit of the noise of the engines and the propellers. Ingress and egress to the seats required contortions not possible except to the young and the athletic, and women hobbled with the skirts of the time would have refused the attempt. All three prototypes were returned to Dornier.

At this point, Flight Captain Untucht stepped into the picture. Untucht, Lufthansa’s chief pilot and a former test pilot for Dornier, had friends in the Air Ministry, and he suggested that the elegant Do.17, with only a few modifications, would make an ideal quick-dash bomber. The forward passenger box was ripped out and replaced with radio equipment and a seat for the operator. Portholes were eliminated. The fuselage was shortened by twenty-two inches, and the single rudder was replaced by twin rudders to eliminate the plane’s only evil, a tendency to yaw left and right. A sixth prototype, the Do.17V6, was fitted with different engines, twelve-cylinder Hispano-Suiza inlines developing 775 horsepower at takeoff, and, thus modified, the new bomber entered flight trials in the fall of 1935. With the throttles bent all the way forward, the V6 clocked a sizzling 243 miles per hour, faster than Heinkel’s famous He.70 Blitz, and 13 miles per hour faster than Britain’s latest biplane fighter, the Gloster Gauntlet.

The argument was advanced within the Luftwaffe Technical Office that since chance had provided the long-discussed highspeed bomber, production should commence without further modifications; no armament was needed; speed alone was proof against interception. Sagely, the suggestion was vetoed. After all, it was only a question of time before tomorrow’s enemy, whoever that might be, produced faster fighters. The Technical Office ordered guns installed. The Do.17 went through yet two more prototype versions, ending with the V9; then full production began for the Luftwaffe with model Do.17E-1. Armament included a 7.9 millimeter (.30 caliber) machine gun firing downward and another gun mounted on top of the fuselage just aft of the wing. The maximum bomb load was 1,650 pounds, i.e., a pair of 550-pounders and four 110-pound general-purpose bombs. Speed was reduced to 220 miles per hour at sea level, and the thin, low-drag wings accommodated fuel enough for a tactical range of barely 310 miles — enough, however, for a highspeed run and back from the Oder to Warsaw, from the Rhine to Paris, or from Düsseldorf to London. With a quantity order in hand, Dornier produced an innovation in the manufacturing process: the DO.17’s airframe was broken down into component parts for ease in subcontracting, a technique that not only resulted in early dispersal of the German aircraft industry, but made it easier for replacement of damaged airframe parts at group and even squadron level.

The other major contributor to the Luftwaffe’s plowshares-into-swords scheme was Ernst Heinkel. Even before the last of the seventy-two He.70s ordered by the Air Ministry rolled off the line at Warnemünde, its derivative big brother was being assembled in the new plant at Marienehe. Unlike the Do.17, Heinkel’s 111 was laid out on the drawing board as both a bomber and a transport right at the start. In civil dress, the He.111 carried ten passengers — four forward and six aft. In between was an improvised space Lufthansa called a smoking compartment, but which was in reality the bomb bay. The He.111, powered by the BMW VI engines, was a much larger airplane than the Do.17 — the wings, broad and elliptical, spanned fully eighty-two feet — and was nearly a ton and a half heavier unladen. Even so, the first test flight on February 24, 1935, produced a top speed of 217 miles per hour, and a pilot verdict that the handling characteristics were delightful, even superior to those of the famous He.70 Blitz. The Luftwaffe ordered ten He.111s in full military configuration, including three machine-gun positions, a longer fuselage, and a many-windowed plastic nose section for the bombardier. Ballasted for the maximum bomb load of 2,200 pounds, the gross weight of the bomber shot up to more than six tons, and the cruising speed dropped to under 170 miles per hour. Luftwaffe test pilots at the Rechlin proving center complained that the He.111 required excessive stick pressures and, in general, was mulish in flight. All ten were rejected — but Heinkel later sold them at a handsome profit to Chiang Kai-shek.

Now Daimler-Benz came forward with a new engine that not only saved the He.111 program, but boosted the dreams of fighter plane designers, who were frustrated at the meager horsepower available inside Germany. The new power plant, an inverted V, twelve-cylinder inline, boasted 1,000 horsepower at takeoff, and this made all the difference. Powered with the DB 600A engines, the fifth prototype of the new bomber reached 224 miles per hour in trials at Rechlin despite the extra 838 pounds added to the gross weight by the bigger engines. Could Heinkel have all the new Daimler engines he wanted for series production of the He.111? He could not; they, and improved variants already in the works, were earmarked for the fighter program, but the Luftwaffe was so keen on the prospects of the He.111 in that Daimler was asked to provide similar, if slightly downrated, power plants for the new Heinkel bomber. With certain structural modifications — including altering the pure ellipses of the wings to a more straight-line shape in the interests of simplifying and speeding up shopwork — and equipped to mount DB 600C engines offering 880 horsepower, the He111B-1 was ordered into full production.

Heinkel’s production capacity was strained to the limit, but relief was promised with the visit of Colonel Fritz Loeb, a young Luftwaffe officer attached to the Technical Office. Loeb told Heinkel that the air force wanted yet another factory built, one devoted exclusively to the output of He.111s at an initial rate of one hundred a month. Heinkel, already heavily overspent on the new works at Marienehe, asked where the funds were coming from; he had no intention of going into hock with the moneylenders. Loeb told him the Luftwaffe would pay for everything, that money was no problem. Indeed it was not; the Luftwaffe budget was increasing by quantum jumps. Under Special Plan XVI for fiscal 1933-1934, the Luftwaffe was allotted $30 million, of which $10 million was siphoned from funds available to the army and navy. For fiscal 1934-1935, the amount was increased to $52 million, and from 1935 onward, the Luftwaffe had at its disposal $85 million in one budget and a whopping $750 million in a separate black fund financed through interest-bearing notes sold by the government to the Reichsbank. This scheme was concocted by the Reichsbank’s president, financial wizard Hjalmar Schact, who kept the transactions secret in order to avoid inflation at home and loss of confidence in the reichsmark abroad.

Colonel Loeb specified that the new plant must be located near Berlin and made it clear that the factory must be laid out with war in mind. He told Heinkel, “Not in a city — no compact block of buildings, but everything scattered in case of attacks from the air.” Heinkel pointed out that dispersion resulted in production inefficiency with consequent loss of profit margins. “Don’t worry about it,” Loeb said, “it isn’t your money.”

Heinkel’s scouts roamed the countryside near Berlin and came back with the report that the hilly, wooded stretch of heath near Oranienburg seemed ideal. Oranienburg was only eighteen miles north of the heart of Berlin, and an electric tramline connected the two places. The major drawback was the absence of water. Heinkel sent for a diviner, who plodded across the vacant spaces with a forked stick, and shortly afterward reported a strike. Sure enough, ample water was found only six feet beneath the surface. Heinkel consulted Hitler’s architect, young Albert Speer, and plans for the Oranienburg works were completed at the beginning of April 1936. The plant was broken down into eight major workshops, many of them hidden under the trees. Despite the possibility of air raids, Heinkel later boasted of the plant’s “vast areas of glass framed in steel and red-glazed brick.” Deep shelters were dug, however, and the factory ran its own large fire department. New track was laid connecting the complex with the main line running from Berlin to Oranienburg, but rail traffic was necessarily intended for delivery of raw materials, and Heinkel realized that dependence upon the tram for getting workers back and forth from Berlin was only asking for trouble. A workers’ town was built on the site, comprising twelve hundred homes, a school, a town hall, theaters, shops, laundries and a swimming pool. Ground was broken on May 4,1936, and a year to the day later, the first He. 111 bomber taxied out of the assembly shop to the cheers of thousands of workers and invited guests. Oranienburg was the German aviation industry’s showcase, and the Luftwaffe used it to impress — and intimidate — visitors from abroad.

The high-speed medium bomber program was purely a Luftwaffe idea, but the concept of pinpoint bombing of highly selected, individual targets using specially constructed dive-bombers releasing loads along the plane’s near-vertical axis of flight was borrowed from the United States Navy. That the concept was hammered into operational reality over stubborn opposition and at great personal risk to its prophet was due to the fiery dedication of one man: a civilian barnstormer?, Germany’s greatest living ace from the war, Ernst Udet.