In the first century B. C. E., life in central Europe was transformed when the Germanic peoples, newcomers to the region, migrated into the area of modern-day Germany. Defined by their shared language, a cluster of Indo-European tongues classified as Germanic by linguists, this ethnolinguistic group seems to have originated in northern Europe. These various tribes did not form a cohesive group, waging constant warfare among themselves and living alongside and intermingling with other peoples during their extensive migrations. The most important of these interactions was with the Celts, who had dominated the region before the appearance of the Germanic tribes.

While sources are hazy for the ancient period, and archaeology has not been able to provide conclusive information, it appears that the migrating Germanic tribes moved from the area that is today southern Scandinavia and northern Germany. In the course of their migrations, they moved to the south, east, and west, coming into contact with Celtic tribes in Gaul and Iranian, Baltic, and Slavic peoples in eastern Europe. During this period, Germanic languages became dominant along the Roman frontier in the area of modern Germany, as well as Austria, the Netherlands, and England. In the western provinces of the Roman Empire, namely, in the Roman province of Gaul, situated in modern-day France and Belgium, the Germanic immigrants were influenced deeply by Roman culture and adopted Latin dialects. The descendants of the Germanic-speaking peoples became the ethnic groups of northwestern Europe, not only including the Germans, but also the Danes, Swedes, Norwegians, and Dutch.

Roman sources are often confused and contradictory in their attempts to identify the menacing Germanic “barbarians” they encountered along their borders. Thus, Roman authors such as Julius Caesar used vague terms such as Germani to describe the various Germanic tribes that settled in the area. While scholars are unsure about the extent to which these diverse peoples represent distinct ethnic groups or cohesive cultures, Roman sources mention a range of Germanic tribes including the Alemanni, Cimbri, Franks, Frisians, Saxons, and Suebi.

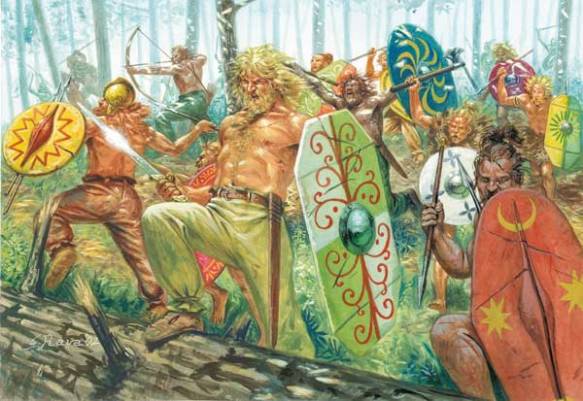

Caesar marched against the latter of these tribes, the fearsome Suebi, in his conquest of Gaul. In his account of this campaign, he describes these Germanic warriors, whom he compares explicitly with the Celts. According to Caesar, the Germanic tribes he encountered gave primacy to war, rather than to religion or domestic life. Their religion apparently lacked an organized priesthood and centered upon the veneration of nature, and Caesar suggested that the Germanic tribesmen devoted all of their energies to gaining renown in battle.

Caesar also describes the pastoral economy of the semi-nomadic Germanic tribes that he encountered across the Danubian frontier. Again, he highlighted the Germanic tribes’ single-minded focus on warfare, recording that-unlike the Romans-they eschewed both wealth and luxury, living off conquest and raiding. For Caesar, this warrior ethos made the Germanic tribes into formidable enemies, and he contrasted the military vigor of the Germanic tribes with that of the more civilized Celts. Accentuating the bellicosity of the Germanic peoples, he found the once formidable Celts, seduced by Roman luxury, lacking by comparison:

There was formerly a time when the Gauls excelled the Germans in prowess, and waged war on them offensively, and, on account of the great number of their people and the insufficiency of their land, sent colonies over the Rhine . . . but their proximity to the Province [the Roman province of Gaul] and knowledge of commodities from countries beyond the sea supplies to the Gauls many things tending to luxury as well as civilization. Accustomed by degrees to be overmatched and worsted in many engagements, they do not even compare themselves to the Germans in prowess. (Caesar in M’Devitta 1853: 153)

Tacitus’s Germania

Julius Caesar was not the only Roman to describe the Germanic tribes who migrated into central Europe and threatened the Roman Empire’s Rhine-Danube frontier. Another was Gaius Cornelius Tacitus (ca. 55 C. E.-120 C. E.). Tacitus was a Roman aristocrat born 150 years after Caesar, in Gaul, the province that the emperor had won. He enjoyed a successful political career, becoming senator, consul, and eventually governor of the Roman province of Asia, shortly before his death. In a work known as Germania, written in 98 C. E., Tacitus described the Germanic tribes, providing a detailed ethnographic account. Despite its polemical intent-it was written in order to contrast the virtue and vigor of the “barbarians” with the decadence and debility of the Romans-and its reliance on secondhand accounts of the Germanic tribes’ customs, his work provides an interesting picture of the Romans’ views of their “barbaric” northern neighbors. Scholars doubt whether Tacitus was ever stationed on the Roman frontier, but he made use of learned sources, including Caesar’s and Pliny’s earlier accounts of the Germanic peoples, in crafting his work. He may have even consulted with Roman soldiers or merchants who had been in direct contact with the Germanic tribes.

In one unfortunate passage, one that would have dire consequences when rediscovered by rabid German nationalists in the 19th century, Tacitus describes the physical power of the Germanic warriors, explain ing it as a function of their “racial purity.” Marveling at the imposing stature of the Germans, the Roman author maintains that the Germanic tribesmen were “untainted by inter-marriage with other races, a peculiar people and pure like no one but themselves” (Tacitus 1914: 269). Given what is known today of the contact and intermingling between Celts and Germanic peoples in antiquity, and the fluid tribal allegiances among the Germanic peoples themselves, Tacitus’s characterization of the Germans’ racial purity is doubtful.

He seems more reliable when describing the formidable military might of the Germanic tribes and the source of their remarkable cohesion on the field of battle. According to Tacitus, the Germanic tribes chose their war chieftains according to their merit as military leaders and their feats of valor on the battlefield. Furthermore, these chieftains did not exercise arbitrary authority and ruled only so long as they led their people to victory. In Germania, he writes, “They take their kings on the ground of birth, their generals on the basis of courage. These kings have not unlimited or arbitrary authority, and the generals do more by example than by command. If they are energetic, if they are conspicuous, if they fight in the front, they lead because they are admired” (Tacitus 1914: 275).

For Tacitus, the secret to the Germanic tribes’ formidable military might was the cohesion of tribal society. The Roman author maintained that unlike the imperial legions of Rome, the Germanic war-bands were composed of clans and families, and their warriors fought alongside their own kinsmen, vying for their respect. In this warrior society, individuals sought the esteem of their peers through conspicuous displays of valor, each seeking to outdo the other in feats of bravery. Young warriors sought to gain the respect of their kinsmen and the recognition of the chieftain, who doled out gifts of plunder to the bravest warriors. Likewise, according to Tacitus, the Germanic tribesmen brought their women and children to the battlefield. Consequently, the Germanic warriors gained remarkable strength from the exhortations of their women, and ferocity from the knowledge that they were defending their families from slaughter and enslavement: “The strongest incentive to courage is that neither chance nor casual grouping makes the squadron or the wedge, but family and kinship. Close by them, too, are those dearest to them, so that they hear the wailing of women and the child’s cry. Here are the witnesses who are in each man’s eyes most precious, here the praise he covets most” (Tacitus 1914: 275).

Continuing his examination of the tribal war-band, Tacitus also discusses the egalitarian nature of political life within the Germanic tribes, for him in stark contrast to the autocratic domination he endured under the Roman emperors. According to Tacitus, the Germanic tribes assembled periodically to deliberate over important matters. While chieftains spoke first, each warrior enjoyed the right to address the assembly before decisions were reached through mutual assent. The cohesion of the Germanic war-band was also maintained through lavish, drunken feasts, where tribesmen enjoyed the fruits of plunder and the largesse of their chieftain. While Tacitus’s treatment of the religious rites of the Germanic peoples, based upon earlier distorted Roman accounts, sheds little light on their beliefs, his account of their marriage customs praises their homespun morality: “the marriage tie with them is strict: You will find nothing in their character to praise more highly” (Tacitus 1914: 289). For Tacitus, the praiseworthy marital fidelity of the Germanic peoples stands in stark contrast to the decadence he perceived within the households of imperial Rome. According to the Roman aristocrat, the Germanic tribes were monogamous and punished adultery harshly. Even the dowry shared by the young couple reflected the martial spirit Tacitus discerned among the tribes, as the groom gives his bride “oxen, a horse and bridle, a shield, and spear or sword” as marriage gifts and “she herself in her turn brings some armor to her husband.” Considered their “strongest bond of union,” these gifts remind them of the primacy of war in Germanic culture (Tacitus 1914: 289).