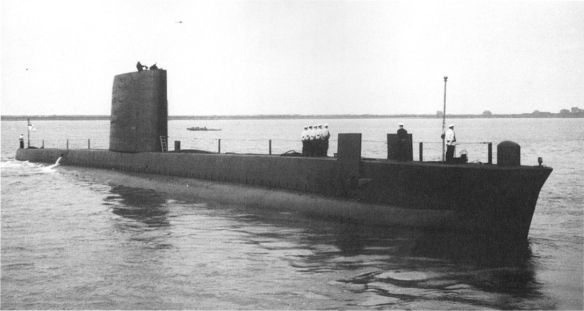

Porpoise, the first post-war operational submarine design. For their day, they were exceptionally quiet.

By 1948 it was recognised that anti-submarine warfare (ASW) would be the primary role of the Royal Navy’s submarine force. Subsidiary to this, it was clear that they would have to spend much operational time providing targets for the training of surface ASW vessels and aircraft and the development of ASW tactics. In addition, it was thought likely that British submarines could operate against Soviet merchant ships supporting their army in the Arctic and possibly the Baltic and Black Sea. The German Type XXI had shown what conventional technology could do when required. The concept was brilliant and original but the individual techniques used for increased diving depth, greater battery capacity, more powerful electric motors and streamlined hull form were all well known. First priority was to use such techniques in modernising existing submarines and then to build a new design diesel-electric boat.

Six Porpoise class submarines, designed by R N Newton and E A Brokensha, were ordered in April 1951, and two more in 1954. They were a little bigger and somewhat shorter than the ‘T’ conversions, but improved design methods and UXW steel together with new structural design methods gave them a considerably increased diving depth. A model of the very long engine-room collapsed during tests at NCRE and a number of extra deep frames were fitted in the final design. They were exceptionally quiet for their day, mostly by careful attention to detail in the design and support of their machinery.

The engines were Admiralty Standard Range I (ASR I) designed at AEL, West Drayton and built first at Chatham Dockyard, an unusual case of ‘in-house’ machinery development. They were to prove very successful even though some of the design aims proved over-ambitious. Great attention was paid to habitability, including air-conditioning. The six bow tubes had rapid reloading gear so that a second salvo could follow very soon after the first, but this was heavy and not very reliable. Torpedoes could be fired at much greater depth than in previous classes. Submerged endurance was expected to be 55 hours at 4kts, about three times that of any previous RN boat.

The DNC, Sir Victor Shepherd, explained in 1955 that the submerged speed had come down from 17kts to 16kts, which he blamed on the use of reduced-noise propellers of lower propulsive efficiency and on caution in estimating full size performance from model tests. Submerged endurance on batteries had been further reduced following a re-assessment of auxiliary load by the Director of Electrical Engineering. At 4kts the auxiliary load was equal to the power for propulsion. In consequence, the nominal endurance at 4kts was reduced from 55 hours to 40 hours. Problems with the UXW steel, led to a reduction in diving depth from 625ft to 500ft. In 1953 the design had been lengthened 4ft to accept an increase in machinery weight. Despite the fact that they fell short of performance targets, they were probably the best submarines of the day within NATO, and considerably superior to the Soviet ‘Whiskey’ class. They were deeper diving than either the ‘Whiskey’ or the German Type XXI (both 400ft), faster than the ‘Whiskey’ but 1kt slower than the XXI, and far quieter than either.

They had noise-reduced propellers, benefiting from trials on surface ships and on Scotsman. Initially, these were very prone to ‘sing’, in which eddies are shed from the trailing edge, alternately from one side and then the other, exciting a resonant vibration of the blade which, in turn, makes the eddy shedding worse. It is said that Rorqual could be heard leaving the Clyde on the west coast of Scotland from a listening station on Long Island. The USN had similar problems and there was much interesting discussion on both theoretical and empirical solutions either seeking to control the eddy shedding or to prevent vibration by damping. Luckily, the Porpoise propellers had been designed before Conolly’s work on propeller strength and were stronger than necessary. This made it possible to cut grooves in the blades, which were filled with a damping material which gave a complete cure.

They had a good sonar fit aided by their low noise level and proved successful in a long service life. Top speed was about 16kts submerged and they had an endurance of 9000 miles on the surface.