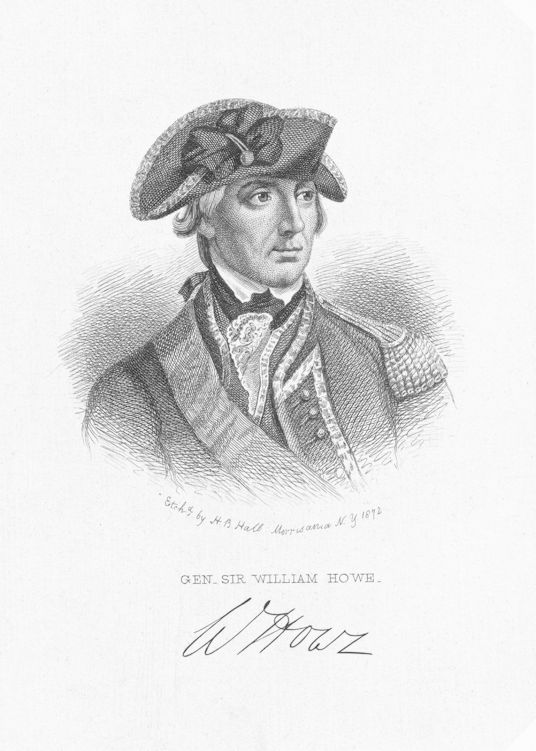

William Howe. The senior-most of the three major generals sent from Britain to Boston in the spring of 1775, Howe was a skilled and innovative commander. But his heart was not in the war, and he would take much of the blame—unfairly, as it turned out—for the high British casualties at Bunker Hill.

Sir Henry Clinton. Contentious, shy, and difficult, Clinton was the most learned of the three newly sent British major generals. He would play an important part in the closing phases of the Battle of Bunker Hill. In later life, Sir Henry obsessed over his role in the battle, and was firmly convinced that the battle would have gone better for the British if Thomas Gage had listened to his advice. Portrait by Andrea Soldi.

Sir John Burgoyne. Burgoyne was by no means the equal of leaders like Howe and Clinton, but his boisterous presence in Boston after May 1775 helped to bolster sagging British morale. Portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

The most anticipated arrival, though, came on Thursday, May 25, 1775. HMS Cerberus, a sixth-rater of twenty-eight guns, threaded its way into Boston harbor late that afternoon. As the crew brought the warship alongside the Long Wharf and secured it there, a crowd gathered to greet its distinguished guests. The first was a courier, bearing the welcome news—welcome to Admiral Graves, at least—that Graves had been promoted to Vice Admiral of the White, a considerable distinction, given his unimpressive performance thus far. Then came the real attraction: the three major generals. William Howe, Sir Henry Clinton, and Sir John Burgoyne stumbled clumsily down the gangplank and onto the wharf, where they were quickly whisked away to Gage’s headquarters at Province House.

They made a curious and unlikely trio. Not one of them had been eager to come to America, and in fact each of them had protested against his orders. But no one else was suitable. Jeffrey Amherst, the highest-ranking general in the service and a hero of the French and Indian War, had steadfastly refused to go; he knew, probably better than anyone save Gage, how quickly a tour of duty in America could wreck a career. Gage’s second-in-command, Major General Sir Frederick Haldimand, was an experienced soldier and had been a capable administrator in Canada. He had been in Boston since the previous fall—Gage had called him in after the Powder Alarm—and Gage had given him very little to do while he was there, but still Sir Frederick knew the situation on the ground intimately. Haldimand’s main failing, though, was that he was Swiss-born, and the feeling in London was that a foreigner couldn’t be fully trusted in a domestic squabble such as the American rebellion.

As major generals, Howe, Clinton, and Burgoyne each ranked below Gage. They had not been sent to replace him—not explicitly, and not yet—but their presence had a meaning that poor, frustrated Gage could not mistake: they were there to remind him that the king and Parliament expected action, immediate action, and that the rebellion must be crushed now.

William Howe was the senior of the three in rank. He was well acquainted both with Gage and with America. He and his two older brothers had made their careers in the king’s service. Their mother was half-sister to King George I, which assured them of rich opportunities and a good life, but all three proved themselves to be exceptional leaders. George Howe, one of the most capable British commanders in the French and Indian War, would almost certainly have risen to the very highest ranks had his life not been tragically cut short by a French musket ball during Abercrombie’s botched assault on Fort Carillon in 1758, gasping out his last breaths in the arms of his friend Israel Putnam. The provincials loved him—loved him so much that Massachusetts honored him with a memorial in Westminster Abbey. The third brother, Admiral Richard Howe, was already well on his way to a distinguished naval career.

And William shared their qualities. He had been an officer since the age of seventeen and had fought in Europe during the War of the Austrian Succession. It was in America, though, that Howe made his name. He was one of the younger, progressive officers—like Gage—who embraced the new tactics and the concept of specially trained light troops. In General Wolfe’s improbable assault on the fortress of Quebec, it was thirty-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Howe who led his light infantry up the Heights of Abraham, clambering up the sheer rock face as if he were a boy. After the war he was widely regarded in military circles as the foremost expert on light infantry and irregular warfare, and he spent much of 1774 training light troops on Salisbury Plain.

Like Tommy Gage, William Howe knew Americans, understood the American character, and though he found them wanting in some respects, he had a healthy regard for their abilities. Howe liked Americans and disliked the prospect of making war on them. One year earlier, as a solid Whig, he had been elected to Parliament from Nottingham on the solemn promise that he would never take up arms against the king’s subjects in America. He meant it. But the king had other ideas, appointing Howe to command under Gage. Howe had no choice; he obeyed his king. Many of his constituents, many of his fellow Whigs who sympathized with the colonials, were very disappointed in the general.

Despite his distaste for the assignment that had fallen into his lap, Howe was a good choice. There was probably no one in the entire army who so thoroughly fit the mold of an ideal soldier than Howe. He had an obvious physical presence, much like his later adversary Washington: he was six feet tall, broad-shouldered, and full-lipped, with a dark complexion and a stormy demeanor. Introspective and thoughtful, an excellent tactician and a passable strategist, Howe was nonetheless possessed of a common touch that made him invariably popular with the men who served under him. Physical courage accounted for part of that popularity; he was one of those rare commanders who would not ask his boys to do anything he wouldn’t do himself. On the other hand, his considerable charm was partly his undoing: Howe loved the high life and although married was very much a ladies’ man. His soft life showed in his noticeably ample midriff, and his love for women would eventually distract him from his duties.

In nearly every way, Howe was a very different man from the next general of the trio, Sir Henry Clinton. Clinton was only a few months younger than Howe but little like him in experience or character. He was actually born in America, where his father, Admiral George Clinton, served as a naval commander, governor of Newfoundland, and then governor of New York. After a brief and uneventful tour of duty as a junior officer during King George’s War, Henry left the colonies for Britain at the age of twenty-one. Family influence advanced him rapidly. By age twenty-six he found an appointment as aide-de-camp to Sir John Ligonier, soon to be commander-in-chief of the army in Britain; by twenty-eight he was a lieutenant colonel. He never returned to America—not until now, that is—and his extensive service in the Seven Years’ War was entirely on European battlefields. That was no minor issue. There was a divide, subtle but wide and tangible, between high-ranking British officers who made their careers in America and those whose experience was primarily European. Officers trained in the “German school” held themselves to be more erudite, more experienced in the kind of warfare that truly mattered, than their comrades who had wasted their lives fighting against irregular Canadian militia and wild savages. Little surprise, then, that Clinton was as unwilling as Howe to risk his fortune in America. “I was not a volunteer in that war,” he noted plainly in his memoirs. “I was ordered by my Sovereign and I obeyed.”

To his credit, Clinton was as well read and thoughtful as Howe, but he was not a particularly likeable man. Short, stooped, and introverted—“a shy bitch,” he once described himself—he was ready to perceive slights where there were none, ready to bristle at any kind of criticism. He was outspoken, which was not in itself a bad trait . . . but he had great difficulty finding merit in the views of others when they conflicted with his own. He felt smugly superior in being a product of the “German school,” and since Howe and Gage were pupils of the “American school” Clinton would, from the very moment he crossed the threshold of Province House, feel that his two superiors dismissed his opinions out of hand. Brilliant but suspicious, brave but difficult, Clinton’s personality would hamper his command effectiveness for the remainder of his career.

And John Burgoyne—“Gentleman Johnny,” as he was often called, for his aristocratic air and his sartorial tastes—shared almost nothing in common with either Howe or Clinton other than rank and nationality. At fifty-three, he was the oldest of the bunch, though it was hard to tell from appearances. John Burgoyne had a dashing but unserious manner and a handsome face, and although soldiering was his career it was hardly his life. Like most general officers, he had purchased his commission while yet in his late teens; he unintentionally put his career on hold early on, though, eloping with a daughter of the influential Lord Derby and taking up a voluntary exile abroad. He returned to the good graces of his father-in-law, and to his vocation, at the beginning of the Seven Years’ War, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1758. He proved valuable in promoting the concept of light cavalry in the British service, and justly earned a reputation for his progressive notions of military discipline—notions that included such revolutionary ideas as that officers should refrain from verbally abusing their men, and that even enlisted men should be treated as thinking individuals. In this sense, at least, Burgoyne was truly ahead of his time. Otherwise—except in his own estimation—he never distinguished himself as a soldier, and never would. What he prided himself on most, though, was his literary ability. Burgoyne fancied himself a playwright, penning two plays before called to duty in America. One of them, a maudlin little piece titled Maid of the Oaks, was produced just before Burgoyne’s departure for Boston in 1775.

In politics, Gentleman Johnny was just as flamboyant, though not without substance. As a member of Parliament he led the crusade against corruption in the East India Company, never shrinking from ruffling feathers when he felt it necessary. His attitude toward America was ambivalent. He had no connection to the colonies or the colonials; he counseled against the use of force, yet thought of America as a “spoiled child.” Plainly, Burgoyne had the least to contribute of the three generals aboard the Cerberus, and he knew it. He suspected that, as junior to Gage, Howe, and Clinton, he would be little more than a useless cipher. Burgoyne hoped that, perhaps, his connections back home might be able to wangle him another appointment—maybe in New York?—one in which he would have at least a chance to shine on his own.

Though the three generals were indeed very different men, close quarters aboard the Cerberus forced them to spend a great deal of time together. Howe and Burgoyne were naturally extroverted and outgoing; not so Clinton. Yet even the “shy bitch” had to be sociable—he was tortured by seasickness for the duration of the voyage, made worse by the cramped quarters that he shared with six other men, and only above deck in the open air could he find a small measure of relief from his illness. Here he, Howe, and Burgoyne fell into easy and familiar conversation, leading to mutual admiration and even something approaching friendship. “I could not have named two people,” Clinton wrote in his memoirs, “I should sooner wish to serve with in every respect.” The three men found, too, that their ideas on strategy were not all that dissimilar. “We do not differ in a single sentiment upon the military conduct now to be pursued,” wrote Burgoyne. Undoubtedly they did agree on one central principle: Gage had been needlessly passive. Yet even with Howe’s extensive knowledge of America, they had very little idea of what lay ahead in Boston’s gilded cage.

They were optimistic and boisterous nonetheless, and none more so than the perpetual actor Burgoyne. As the Cerberus approached Boston harbor on May 25, she hailed another vessel, and their captains exchanged news. Boston, as the crew and passengers on the Cerberus found out, was surrounded by warlike, armed, insolent Yankees who by their very numbers were able to keep Gage’s army immobilized. Burgoyne couldn’t suppress his theatrical nature or his wont to brag. Like an overconfident adolescent, he shouted to the captain of the other ship, “Well, let us in, and we shall soon make elbow-room!”