Unlike the beginning of World War I, Germany entered the second world war of her choice with a very inferior navy, and quite obviously she discounted this arm of her forces (except for submarines), pinning her faith for the third time within a century on the might and resource of a finely equipped land army. Hitler appears to have allocated to the small German Navy of 1939 a diversionary rôle, and the purpose of the pocket battleships was to tie up the attentions of a disproportionately large part of the mighty British and French navies.

Again apart from submarines, of which Hitler probably had about eighty, in 1939 the German Navy consisted of two medium-sized battlecruisers, Scharnhörst and Gneisenau, built by Hitler in defiance of the Versailles Treaty, the three pocket battleships, two heavy cruisers – the Blücher and Admiral Hipper – and half a dozen 6-inch cruisers, as well as some armed merchantmen. The 45,000-ton Bismarck and Tirpitz were under construction, as was the 8-inch heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and other ships. Germany had no aircraft carriers, but was building two.

Numerically the fleets of the United Kingdom and of France were vastly superior to Hitler’s, but they were orthodox in design and therein lay an advantage to the German dictator. However, the combined French and British fleets totalled 21 capital ships (battleships and battle-cruisers), 59 cruisers, and a host of light cruisers, destroyers, sloops, etc., as well as aircraft carriers. Though many of these ships were old and out of date for a modem war, nevertheless Germany had to consider the fact that she was numerically at a considerable disadvantage. Britain especially still ruled the waves.

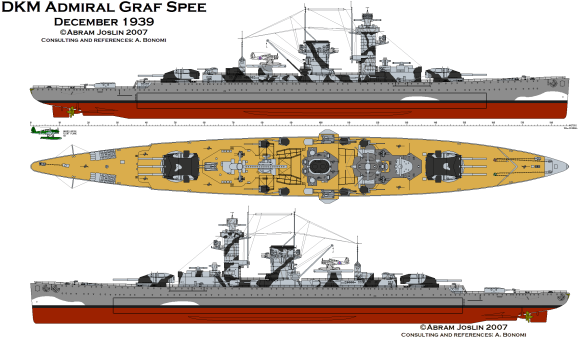

This dictated Germany’s naval preparations for the war Hitler wanted, influencing the design of all the ships built, though most noticeably in the construction of the powerful pocket battleships. The Deutschland, Admiral Scheer and Admiral Graf Spee were cast in the rôle of wolves of the sea, and admirably designed for the purpose.

Before the outbreak of war, Admiral Raeder secretly dispatched his pocket battleships to be “lost” in the world’s oceans, ready in case the war spread to other countries after Hitler’s invasion of Poland. To maintain the pocket battleships at sea, he had tankers and supply ships stationed in strategic areas, so that the marauders could re-fuel and provision themselves and so maintain themselves away from land bases for months, or more than a year if need be.

Out at sea when war was declared, his pocket battleships knew their orders. They were to harry the ships that were vital to the enemy economy, especially to Britain, that island dependent upon the world for so much of her raw materials and foodstuffs.

But the British Admiralty knew the German battleships were out, and knew what to expect from them when war started, so, months ahead of the outbreak of war, they worked on a plan to out-wit and defeat the enemy when the emergency arose. It proved to be a most difficult task. Because of the strength of the pocket battleships, it meant that the search for them had to be conducted by groups of ships, so that if our faster but less powerful ships sighted the battleships, courage, seamanship and a concentration of gunfire might off-set the advantages of the bigger warships.

What was not easily explained, however, was how our ships could get close enough to hurt the thickly armoured Germans without being blown out of the water first. The pocket battleships’ 11-inch guns outranged those of British and French cruisers by several miles, and, according to Raeder’s theory, even if they were overtaken by a superior force, the battleships could pick off their opponents at leisure from a distance out of effective range of their opponents’ 6-inch or 8-inch guns – like a boxer with superior reach holding off an opponent and playing with him.

That was the problem facing the British and French navies, but nevertheless hunting groups of warships were ready even before the outbreak of war, waiting for the pocket battleships to start their killing rôle, and hoping then for the good luck to come up with them.

Unknown to the experts was the fact that the pocket battleships were equipped with the German equivalent of radar. It was crude compared with modern day apparatus, inefficient and prone to break down, but it gave the German raiders a wonderful advantage over their unequipped opponents, in that they could “see” far over the horizon in every direction around them.

It seemed impossible even for hunting groups ever to come up with a raider who could see them from a great distance and take steps to avoid them.

Only the Admiral Scheer had ever been seen in action. This was in 1937. The Deutschland had been bombed while off Spanish waters by a Republican aircraft, which caused the death of several of the crew. On May 29, as a reprisal, the Admiral Scheer was ordered to shell the undefended town of Almeria, which she did, rendering 8,000 homeless and causing injury as well as a vast amount of damage.

This was hailed by the Germans, just getting into their stride so far as propaganda was concerned, as a glorious victory. Later they were to make similar claims about the Battle of the River Plate, again with doubtful accuracy.

When the first raider report came through, the British Admiralty were not certain for some days as to whether the attacker had been a pocket battleship or one of the several armed German merchant cruisers known to be in the South Atlantic. Indeed, even after the reports came through from the survivors, picked up at sea in their lifeboat by the Brazilian ship, the confusion persisted for a while because of the remarkably contradictory character made of some of the descriptions of the enemy. However, in time it began to be accepted that it was a pocket battleship which had started to run amok in the waters off South America.

Very quickly after this, unfortunately, came another report to cast doubt upon the identity and possible position of the raider. It was learned that an attack had been made by a pocket battleship upon a Norwegian merchantman, the S.S. Lorentz W. Hansen, three hundred miles east of Newfoundland. The report of the crew was that the battleship was the Deutschland, but a suspicious Naval Intelligence wondered if perhaps this might not be the same battleship which had sunk the unfortunate S.S. Clement …

It was some time before they were to know the truth – that it wasn’t the same pocket battleship, and that in fact two German warships were roving the Atlantic in search of prey.

The Rawalpindi was the next victim of the Deutschland, to continue briefly the history of that ship. The Rawalpindi, an armed British merchantman, completely out-gunned, nevertheless gallantly went for the German raider when she was attacked, damaging her somewhat with her small guns and finally sinking in action with her colours flying. After that the Deutschland made a run for home down the neutral coast of Norway – a favourite expedient with German home-bound ships.

Again, the British Naval Intelligence was puzzled by the report that the Admiral Scheer was active in South American waters, because according to their information that ship was in German waters.

Deutschland or Admiral Scheer, however, the hunt was on. A raider was loose on the high seas and affecting British interests. That raider had to be put out of the way and quickly, too.

So began a man-hunt – a hunt for an enemy man-o’-war – probably the biggest the world had ever seen. Yet days passed into weeks before the British Admiralty received any further report about the raider’s activities, though in that time the mighty pocket battleship had continued at her work of waylaying and sinking merchant ships in the South Atlantic.