Airfields of the opposing forces around Verdun 1916.

Norman Prince, an American private pilot, had gone to France soon after the war began, to form a volunteer American squadron. He met another American, Edmund Gros, a doctor who had formed the American Field Ambulance Service. They set up a committee and appointed a Monsieur de Sillac as President. Dr Gros and five other Americans, one of whom was the millionaire William K. Vanderbilt, who provided the finance, served on it. Prince was not a member: his purpose was to join the unit and fly. They sought recruits among all the Americans who had already joined the French Army.

Initially, the French opposed the plan. As the static warfare sank into a morass of dreary winter inaction the notion of volunteer fighters from abroad, especially from a country so vast and rich as the USA, began to look appealing. It would be wonderful propaganda. The prospect looked all the glossier because the air forces had already acquired a romantic, individualistic image. From dissuasion, the French turned to encouragement.

The conditions the committee offered the American volunteers were generous, to compensate for their basic pay, which would be that of l’Aviation Militaire and low in comparison with American standards. William Thaw was made a lieutenant and the others would be sergeants when qualified but were joining as mere corporals. They would be given a new uniform every three months; 125 francs per head per month would be paid into the mess fund; for each confirmed victory there would be a bonus of 1000 francs. A month after the squadron came into being other perquisites were added: 1500 francs for a Légion d’Honneur, 1000 francs for a Médaille Militaire, 500 francs for a Croix de Guerre and 200 francs for each citation (a palm) added to it.

The unit was formed on 16th April 1916, under a French Commanding Officer, Capitaine Georges Thénault, and second-in-command, Lieutenant de Laage de Meux. The seven American pilots were widely assorted: one or two were comfortably off, another was a medical student, there was a Harvard graduate; there were footloose adventurers. The squadron was based at Luxeuil. Its symbol, painted large on each side of the fuselage, was the head of a Red Indian in a chief’s eagle-feathered war bonnet, his mouth open as he yelled a war cry. Gros, as a doctor and head of an ambulance unit, remained a non-combatant. Prince was joined by James McConnell, Bert Hall, Elliot Cowdin, Victor Chapman, William Thaw and Kiffin Rockwell. Hall was already in l’Aviation Militaire and had forced down a two-seater Halberstadt. They all had to go through a flying course. Their aircraft were Nieuport IIs and the unit’s number was N124. It was publicised as l’Escadrille Americaine, to which the Germans soon objected through diplomatic channels, because America was neutral. Displaying subtlety and style, the French then suggested the name Escadrille Lafayette: in memory of the Marquis de Lafayette, who had taken a group of Frenchmen to America in 1777 to fight with the colonials for independence from British rule.

The Lafayette pilots lived much like the Sportifs. Officer and NCO pilots messed together in the Grand Hotel. Their sleeping quarters were in a large private house. They did not make an auspicious start, wrecking several machines in bad landings and collisions with ground obstacles. The reporters who flocked to Luxeuil drew no veils over their bad flying or off-duty antics. Some public resentment began to grow against these pampered and apparently useless foreigners. Dr Gros had been busy finding more members for the escadrille, Lufbery among them. Necessity now demanded their presence at Verdun.

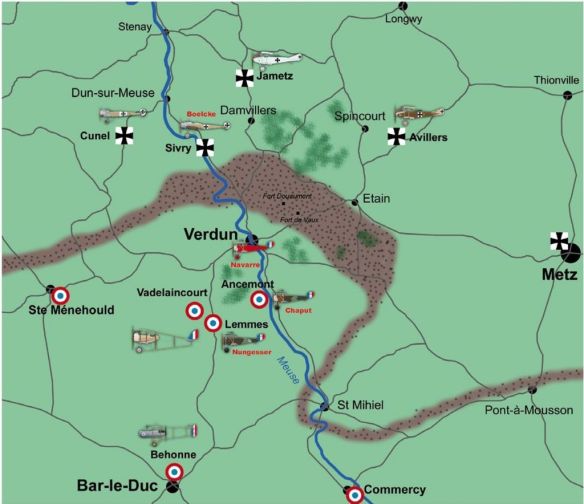

Their aerodrome on the Verdun Front was at Bar-le-Duc, where l’Escadrille Lafayette suffered the casualties that are the lot of any raw squadron. On 24th May, Thaw was the first to be wounded: in a fight with three Fokkers, when a bullet severed his pectoral artery and he almost bled to death. Bullets hit Rockwell’s windscreen and its fragments lacerated his face, nearly blinding him. The next day, his head in bandages, he was on patrol again. Four Fokkers jumped on Chapman out of cloud and a bullet creased his scalp and grazed his skull. Bleeding copiously, he barely managed to return to base. On 18th June, Thénault, Rockwell, Prince and Clyde Balsley, a newcomer on his first operational flight, were attacked by fourteen Fokkers. The enemy circled them, turning inwards to fire in turns. Thenault took his men homewards in a steep dive, but Balsley could not extricate himself. An explosive bullet hit him in the stomach and wounded him severely. Surgeons removed more than twenty fragments and he lived. Chapman and Prince, flying to visit him, were bounced by six Fokkers. Chapman was shot down in flames and became the first American airman to be killed in action.

When, soon after, the Lafayettes were taken out of the line and returned to Luxeuil, Thaw had been given the Legion d’Honneur, Chapman, Rockwell and Hall the Médaille Militaire and Croix de Guerre with one palm. They found two Royal Naval Air Service squadrons, among whom were several Canadian pilots, on the airfield. Immediate mutual liking and good fellowship were struck between the nationalities: British, Commonwealth and American. This was a feature of all relationships between the British and both American and French Air Services. When the American Air Corps arrived in France in 1918, however, its association with l’Aviation Militaire was not always cordial.

The concentration of enemy fighters on Verdun did not noticeably afford any relief to the RFC. During the first six months of 1916 it lost an average of two aircrew a day. The loss of fifty in November and December 1915 had been severe enough. Most squadrons were still a mixed bag of two, three, or even four types of aircraft. Bewildered though pilots may have been by the daily variation of their duties between visual and photographic reconnaissance, escorting others who were thus engaged, or offensive patrols, morale remained high on most squadrons.

Trenchard wasted many lives because he equated aggression with the distance his aircraft penetrated behind enemy lines. As justice has not only to be done but to be seen to be done, so the RFC’s aggressive spirit had to be made obvious. In Trenchard’s scale of values, a patrol that went ten miles into Hunland was ten times as aggressive as one that went one mile, regardless of the quality of the work that was done when the patrol reached its limit. The man who went one mile deep might have a better chance of shooting down enemy aeroplanes than the man who went ten, but that did not seem to matter. This attitude was not only unintelligent but also cruel. British aircraft were inferior to the enemy’s and even an exceptional pilot in a BE2C, Martinsyde, Bristol Scout, FE2, Sopwith, RE7 or Morane, all of which figured on British squadrons, was at a disadvantage against the Fokker, Pfalz, Halberstadt or some of the two-seaters, in the hands of a pilot who might be no better than average.

Trenchard used to visit all his squadrons frequently in his Rolls-Royce staff car. He told the aircrews that he did not ask them to do anything that he would not do himself. But he did not actually do it. This assertion was commonplace in all the Services, but its credibility varied greatly. A platoon, company or battalion commander, a flight or squadron commander, the captain of a naval vessel and an admiral at sea with his fleet, spoke nothing but the truth when he said it.

The RFC was on the threshold of better days, with new fighters soon to appear at the Western Front. Louis Strange had recently been sent back to England for a rest, and his friend Lanoe Hawker’s turn had come when, on 28th September 1915, he was put in command of the newly formed No. 24 Squadron, at Hounslow. He had not had to face the Fokkers at the height of their supremacy, but he had fought for almost a year and his VC and DSO were evidence of the severe stress he must have suffered. He showed physical signs of extreme fatigue.

In January 1916 the squadron was delighted to be told that it was about to receive the new de Havilland DH2 single-seater, which had been specifically designed as a fighter. It is often said that No. 24 was the RFC’s first fighter squadron and the first to be equipped with only one aircraft type. That distinction belongs to No. II Twenty-four, however, was the first homogeneous single-seater fighter squadron. And there is no accuracy in any claim that only a single-seater can properly be described as a fighter. The two-seater Bristol Fighter, when it came along in 1917, was a true fighter of outstanding accomplishments.

The DH2 was a pusher with a Lewis gun mounted in the nose. It did not look as modern as a Fokker or a Nieuport: the pilot sat in an enclosed nacelle, but behind him was an open framework of long spars, braced by struts, attaching it and the wings to the tail unit; and it had the unreliable Gnome single-valve 100-h.p. rotary engine. At sea level its top speed was 93 m.p.h., but at the heights at which it would do its work this fell to around 77. Its ceiling was 14,000 feet and to reach 10,000 feet required 25 minutes. Speeds, rates of climb and ceilings for aeroplanes were still imprecise. Much depended on how they were rigged and the condition of individual engines. Two of the same kind could have a disparity of five to ten per cent in speed and rate of climb.

Another new fighter squadron, however, beat Hawker’s in the race to get to the Front. No. 20, commanded by Major G. J. Malcolm and equipped with the FE2B (familiarly the “Fee”) two-seater, arrived there on 23rd January. Like the DH2, the FE2 had been designed by Geoffrey de Havilland and was a pusher with an enclosed nacelle and a latticework fuselage of beams, spars and bracing wires ending in the empennage. Following the standard British practice, the observer sat in the front cockpit, provided with a forward-firing Lewis gun. Most Fees also had a second Lewis on a telescopic mounting behind his seat, which fired upwards over the wing. The FE2 was heavier than the Fokker, so its 120-h.p. Beardmore engine did not give it quite the latter’s speed, but it was equally manoeuvrable. Every pusher posed the same danger to its pilot in the event of a crash: the heavy engine was hurled forward and crushed him. On the other hand, it was an effective shield against bullets fired from astern. Of course, if the bullets stopped the engine, a resulting crash landing would flatten the pilot anyway.

Of the twelve pilots — all officers — who joined Hawker on 24 Squadron, only the three flight commanders and two others had flown on operations. Because of engine unreliability, familiarisation flying was restricted to two hours so that there would be reasonable certainty of the whole squadron arriving at its destination in France without any forced landings. Hawker was ordered to cross the Channel by steamer on 2nd February 1916 and the rest flew over on the 7th to St Omer. They were immediately put on daily patrols at 14,000 feet from 8 a.m. until 3 p.m. Two aircraft were kept back at three minutes’ notice to scramble in protection of GHQ if the enemy put in a bombing raid.

One of the marvels of all that aircrews accomplished in that war was that they did so much in such adverse physical conditions. It was intensely cold and now that patrols at heights of 14,000 feet and higher were becoming standard the low temperature was painful and incapacitating. Pilots and observers came dangerously close to suffering hypothermia. Frostbite was a common affliction. More dangerous and a greater physical handicap was lack of oxygen. In the 1939-45 war, when all aircraft were fitted with oxygen “bottles”, it was compulsory in the RAF to switch on at 10,000 feet. Tolerance of oxygen deprivation varies and some men switched on sooner. Oxygen starvation causes hallucinations — clouds, for instance, are mistaken for other aeroplanes, mountain ranges, and stranger things — headache, nausea, lack of strength and energy. On top of these handicaps was the nauseating effect of castor oil as an engine lubricant. The fumes caused vomiting and diarrhoea. A tractor rotary engine sent oil spraying back over pilot and observer, reducing vision through windscreen — not all machines had them — and goggles, and blackening faces. Men had to fly with mouth and chin wrapped in a thick scarf. It was Hawker who designed, and had made, the first pair of fleece-lined thigh boots that became known as “fug-boots”. These were a great comfort, but soft-soled and cumbersome and impractical for walking more than a few yards to and from one’s aircraft. Aircrew who made forced landings and either had to evade capture or walk miles to a friendly unit cursed them.

Another grievous handicap in air fighting was the continued unreliability of machineguns. All were prone to jam from many causes. Fusee springs, pawls, buffers, triggers, defects in drums, imperfect rounds, all caused the frustrations of interrupted combat and lost victories.

Within a week, two of 24’s pilots were killed when their aircraft spun in. The DH2 already had a reputation for involuntary and irrecoverable spinning. It was being called “the spinning incinerator”, but there was nothing new about this. The Shorthorn was “the flying incinerator” and various other types were described as incinerators or coffins, because they stalled or spun easily and usually caught fire when they crashed. They were facile epithets, often intended to excuse pilots’ errors. These were not always their fault, but the result of poor and hasty training that sent them into the air before they were fully competent.

The two fatal crashes were potential morale destroyers. Like everyone else, Hawker had carefully avoided a spin. He now took a DH2 up to 8000 feet and spun it several times: to left and right, with and without engine. Nobody was watching. He landed, went into the mess and announced what he had done. Everyone wanted to know how he had done it. When he had explained how a DH2 could be made to recover from a spin, all his pilots hurried into the air to practise it.

In preparation for their first fight Hawker made his pilots practise gunnery day after day, diving at a full-scale outline of a Fokker on the ground. He designed the ring sight that was adopted throughout the Service.

Some of his pilots mounted twin Lewis guns and he encouraged that, not only because it would double their fire power but also because if one jammed they would have a spare. He showed the twin mounting to his Brigade Commander, who promptly forbade it. Had he had to fight in the air himself, the brigadier general would perhaps have approved of it. Hawker experimented with a double ammunition drum, one welded on top of another in the Armament Section, which led to the production of the ninety-four-round drum that was introduced soon after.

The ineptitude of those who designed gun mountings and the senior officers who would condone no modification made by the men who actually had to fight with these weapons was staggering. The DH2’s Lewis was mounted on a universal joint on the left-hand side of the aeroplane’s nose. The majority of pilots, being right-handed, found this awkward. Many had their guns moved to the right. It was some time before anyone did the obvious and had it mounted centrally. Another irritant was that the gun had to be held steady when being fired. This meant that, wherever it was mounted, a hand had to be taken off the joystick or throttle. In addition, the freely moving mount allowed the gun to dance and wander all over the place, even when the handgrip on the butt was firmly held. Hawker had his squadron’s guns fixed rigidly; but not for long: the brigadier wouldn’t allow that either. Hawker then compromised by having the muzzle anchored by a strong spring, which could not be described as a fixed mounting but did reduce most of the straying off aim.

On 24th April 1916 came the chance at last to evaluate the DH2 against the Fokker, when four of 24 Squadron escorted five BE2Cs of No. 15 on reconnaissance. Twelve Fokkers attacked, some circling to prevent the BE2cs from retreating, the others waiting to make their familiar dive and zoom. When it was obvious that the reconnaissance machines had no intention of turning back, and the whole British formation was deep in enemy territory, the circling Fokkers joined their companions. Then the whole lot swarmed down in attack. The DH2s turned with an agility that surprised the Germans and made straight for them. The Germans, disconcerted by this bold tactic, pulled out of their dives and broke to right and left. In a few seconds the DH2s were into them, turning with them or inside them, firing every time they had an enemy in their sights. Two Fokkers pulled out, damaged, and a moment later a third followed. The remainder drew off and circled, trying to draw the DH2s away so that they could attack the BE2Cs. The escort would not be drawn. Their job was to stick close to their flock.

The Fokkers did not attack again. The nine British aeroplanes returned home unharmed. The DH2 had broken the Fokkers’ grip on the British Sector of the Western Front.