The 82nd Airborne Division was about to enter the Hürtgen Forest—the meat grinder that had chewed up so many US Army divisions during the previous fall. By this time virtually the entire area was one of almost complete devastation, reminiscent of the battlefields of the First World War. The towns were ruins, the trees were stumps, and the ground was churned up with countless craters from the terrific number of artillery and mortar rounds fired by both sides during the earlier fighting.

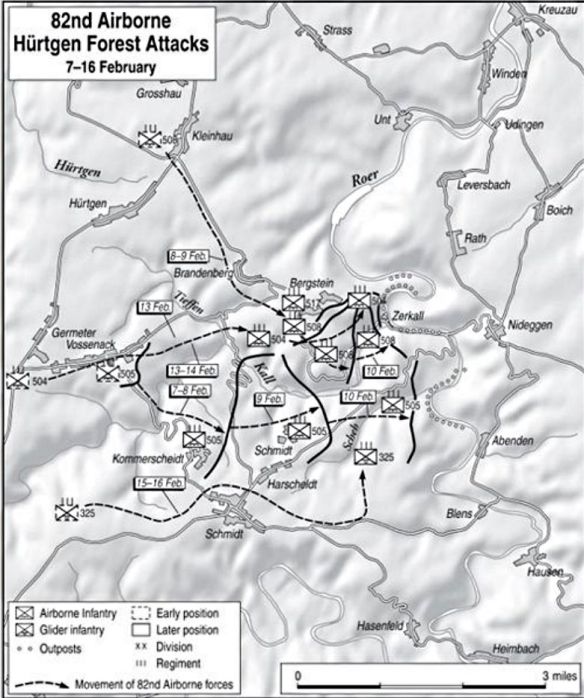

The remainder of the division moved by truck to the area on February 8. That same day the 505th jumped off from positions southeast of Vossenack. The regiment advanced twenty-five hundred yards to the southeast to the town of Kommerscheidt against almost no opposition, except for sporadic artillery firing from the east side of the Roer River and minefields, which caused a few casualties. This movement took the 505th through the Kall River valley, named “Death Valley” by GIs that had fought there earlier. It was the scene of the destruction of most of the 112th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division, the previous November.

It was an unforgettable experience for Christensen, who had seen just about everything during his time with Company G, 505th. “As soon as it got light the next morning we moved out. Most of the snow had melted and we were now plowing through a muddy mess. We were entering an area where some terrific fighting had taken place. The first indication of this was when we noticed the shell holes, plus the havoc the artillery had done to the trees. These in places looked as if someone had taken a giant scythe and mowed them down.

“Proceeding farther down the trail, things got progressively worse. The trees here had been destroyed with a vengeance. Most had been blown to ribbons. Also, scattered among this debris were countless bodies or parts of [bodies]. By their shoulder patch, ‘The Red Keystone,’ you knew they were the remnants of the 28th Infantry Division. The sickening part was they had lain there all winter covered in a blanket of snow. Just a short distance farther in, we came to what had been an aid station. Hundreds of bodies stacked like cordwood along with heaps of amputated arms and legs. Many of the bodies were still lying on litters. These were probably being attended to when Jerry unleashed this massive barrage wiping out this aid station. By the amount of shell holes and destruction centered in this one area, this was no accident. Jerry must have had direct observation. Some of these bodies were just beginning to appear through the melting snow, and a more gruesome sight you wouldn’t believe.

“On the trail until now, we had been enclosed in the forest on both sides. All at once we approached a break in the trees on the left side. Here we had a good view of the valley floor below, which was loaded with wrecks of burned out US tanks. I would say there were well over a hundred in this small area. I couldn’t say a tank battle had taken place there, as I did not see one destroyed Kraut tank. The Krauts were probably sitting back with their 88s and artillery, and annihilated them. Just about all of these tanks had burned, so it would be safe to assume the charred bodies of the crews were still inside.”

As Lieutenant Joe Meyers, with Company D, 505th, moved down the trail with his company, the sights that they witnessed made many of the troopers physically ill. “There was a considerable amount of retching and vomiting going on in [Lieutenant John] Cobb’s platoon.”

The following day, February 9, the division began an attack at 10:30 a.m., in conjunction with the 78th Infantry Division on the left, which had the objective of capturing the huge Schwammenauel Dam, which controlled water flow of the Roer River. River crossings north of this point on the Cologne Plain could not take place until the dam was captured, because water released from the dam could flood the plains to the north. The objective of the 82nd Airborne Division was to reach the western shore of the Roer River, where an assault river crossing upstream from the dam would take place.

The 505th moved out toward the Roer River against only occasional artillery fire meant to harass their movement. Upon reaching the town of Schmidt, Sergeant Christensen found another scene of unbelievable devastation, almost as appalling as the previous day. “What I really saw was just a pile of rubble. The town had been flattened. Here a terrific battle must have taken place. There were bodies strewn everywhere. Some of these, tanks had run over and flattened.

“Charred bodies were hanging out of turrets where the crews had tried to bail out of these burning hulls. You could see an arm or leg lying around, but no body [that] it had been attached to. Had some wild animal been dragging this off to feast on later? You shook your head and wondered, ‘Is this Armageddon? Has the civilized world gone mad?’

“What I had witnessed in the Hürtgen would leave a lasting impression. This place must have been the closest to hell one could get without entering the gates.”

On the left flank, the 2nd Battalion, 508th, moved out from Bergstein, attacking east fourteen hundred yards through extensive minefields, with German artillery firing from across the river and from high ground to the south. The battalion was held up and ordered to dig in, while the 505th awaited ammunition in order to continue its assault and knock out a German artillery piece firing on the 2nd Battalion, 508th, from the high ground to their south.

The division attacked at 2:00 a.m. on the morning of the 10th of February to take the high ground up to the west bank of the Roer. The 1st Battalion, 508th, had as its objective Hill 400. This piece of high ground had been fought over and had changed hands many times during the past three months. Company C led the assault up the hill, but ran into heavy enemy machine gun fire, which was somewhat inaccurate due to the darkness, but it held them up, nevertheless. They attempted to call in artillery, but couldn’t register it accurately, also because of the darkness. The 1st Battalion then deployed Companies A and B on the right flank to envelop the hill from the south. As T/5 William Windom moved around the base of the hill in the Company B column, he heard an explosion. “[Private First Class Joseph G.] Joe Wise, ten yards in front of me, stepped on the first Schu [mine], jumped, hit another, fell, and rolled screaming into more. There was silence, we waited, and at dawn we found we’d been marched through an American minefield as well.

“I found Lieutenant Jones, a new replacement of two days, a West Pointer, with an enlisted man on flank duty, both missing a foot. I got the medics.”

The Germans pulled out before dawn, and the 1st Battalion was on Hill 400 before 9:00 a.m. The 2nd Battalion moved through enemy minefields, but otherwise there was no opposition, and they occupied the ridge to the south of Hill 400 before dawn.

The 505th had received information from patrols the previous night that there was no enemy to its front and moved out to take the high ground west of the river before first light. The 78th Infantry Division was able to secure the massive Schwammenauel Dam, although the Germans had disabled the floodgate valves, causing a steady flow of water to flow north, inundating the Cologne Plain.

Outpost lines were established along the low ground on the west bank to prevent enemy infiltration across the river. The outposts were relieved during darkness every night. The division remained in these positions, with individual units being rotated to allow men to get a hot meal and clean up. On February 15, the 1st Battalion, 325th, moved to a forward assembly area and began practicing along the fast flowing Kall River with tethered boats for an assault crossing of the Roer River. This crossing would be followed by an attack up a 300-foot slope that the Germans had fully prepared for defense, with bunkers, minefields, trenches, and artillery that had pre-registered coordinates for supporting fires.

On the night of February 17, a patrol crossed the Roer River and returned having encountered no opposition. As the 325th prepared for the river crossing, they received their best news in months: it was cancelled.

On February 18, the division was notified that it was being relieved by the 9th Infantry Division, which did so over the next three days. Except for organic transportation units, the division was put on trains and moved mostly in 40 and 8 boxcars, first to Aachen and then to its base camps in the Rheims, France area. The Sissone and Suippes base camps had been taken over by hospitals, and the 325th, 505th, and 508th were billeted in tents around the main posts, while the 504th was moved to accommodations at nearby Laon.

The skeleton force that was the 82nd Airborne Division arrived in France in terrible need of rest, new equipment, and replacements. When Sergeant Paul Nunan returned from a thirty day furlough to the United States, he found the Company D, 505th tents. “I walked around the company area for ten or fifteen minutes before I saw anybody I knew.”

The officers and men were given passes and a few days to rest, while replacements were brought in, many directly from the United States, where they had just graduated from jump school. Other replacements came from the disbanded 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry, and 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion. These veterans were divided among the units, further embittering these fine combat veterans, who retained loyalties with their former units.

Men and officers wounded in Holland and Belgium and those fortunate enough to have been in the Unites States on thirty-day furloughs when the division was fighting in Belgium and Germany returned to the division and helped bring unit cohesion back to their respective outfits.

However, the personnel makeup of most of the rifle companies was almost unrecognizable from those who had jumped in Holland less than six months earlier. Most companies had new officers; many had enlisted men who were now non-coms, having assumed those responsibilities during the fighting of the last two months. Over the next several weeks, numerous promotions and changes in command took place. One example of this was the replacement of Lieutenant Colonel Krause, the 505th executive officer, who was rotated home. Major Talton Long succeeded him as executive officer, while Captain James T. Maness was promoted to major and took over command of the 1st Battalion, 505th.

Parades and reviews were held, where the decorations for individual and unit valor were awarded. General Gavin spoke to the assembled division and told them that they would be getting in on the fighting to finish the war in Europe.

The division began more training, working to rebuild teamwork in the units decimated in the earlier fighting. The veterans were tired of the repetitious training they knew by heart. But the young replacements had to learn the tricks and techniques that would not only keep them alive, but would help insure the success of the unit in combat.

Rumors swirled that the division would jump across the Rhine River to open the way into the heart of Germany and that the division would jump into Berlin to grab it before the Russians. The first rumor was dispelled on March 7, when the First Army seized the Remagen Bridge over the Rhine River.

During the next month there were several alerts for possible missions, and a couple of practice jumps were held. On March 14, the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 508th made a practice jump to maintain their jump status. A tragic accident occurred that morning when the 1st Battalion jumped. As the troopers began jumping, one of the C-47s in the rear of the serial lost a propeller and began to lose altitude, flying down through the helpless paratroopers, catching the chutes of some of the troopers on its wings and tail. It crashed, bursting into flames upon impact. Seven paratroopers were killed, along with four members of the plane’s crew.

When Private First Class Lane Lewis, with Company G, heard about this disaster, he couldn’t help but be nervous when his battalion jumped the following day. “Everyone in our battalion had heard about what had happened yesterday. As I jumped out, I looked back at the planes that were in the rear of the formation. I was not anxious to have a repeat performance from yesterday’s jump. We all made it to the ground safely. It was so very sad, that this close to the end of the war, eleven men lost their lives to an accident.” It was particularly haunting for those who had made it through all of the combat and had to wonder if they might too die in a training accident.

On the morning of March 24, Private First Class Lewis looked up when he heard the sound of hundreds of planes. “A large formation of C-47s towing gliders was seen as they flew overhead. We wondered where they were headed. We later learned that [the 17th Airborne Division was] making a combat jump into Germany to secure a bridgehead over the Rhine River [Operation Varsity]. This river was the last major barrier to the interior of Germany. We were only too happy not to be going along. The war against Germany was coming to a close. The Russians were advancing to the city of Berlin. The British had crossed the Rhine River.”

The second rumor of a combat jump into Berlin was put to rest when, on April 2, the division was loaded on 40 and 8 boxcars once again for a combat operation somewhere in Germany. On March 30, General Gavin had been called to XVIII Airborne Corps headquarters where he received orders to move the division to a location southwest of Bonn, Germany. The following day the division was attached to the Fifteenth US Army and ordered to patrol the west bank of the Rhine River, across from a huge pocket of trapped German forces in the Ruhr industrial area.

However, the division would make the trip without the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, which was detached when division strength was reduced to the TO&E (Table of Organization and Equipment) level, which only authorized one glider regiment (the 325th) and two parachute regiments (the 504th and 505th). The 508th, as an attached regiment, had been a valuable asset of the 82nd Airborne Division, and they were missed. After everything the regiment had done as part of the division, the troopers of the 508th considered themselves to be an integral part of the 82nd and hated ending their association with the All Americans.

The 508th was detached for a potential special mission. On April 4, Private First Class Lewis boarded a truck that was part of a convoy that trucked the 508th to airfields near Chartres, southwest of Paris. “We were prepared to jump on as little as forty-eight hours’ notice to liberate any prisoner of war camps, should the Germans resort to atrocities.”

On the evening of April 2, the trains carrying the division began unloading at a single rail siding at Stolberg, Germany. It took all of the following day for the division to fully debark from the trains, but this was completed shortly before midnight on April 3–4.