Japan’s aggressive intentions toward China had first exploded into war in the 1890s, when it gained important trade and territorial concessions from China after a short war. Japan’s ambitions were not abated, however. In 1931 it seized Manchuria, set up a puppet government, and renamed the territory Manchukuo—a virtual Japanese colony. Then, in 1937, Japan attacked again in a full-scale war. By the time Japan attacked Pearl Harbor—and every American, British, and Dutch possession or base within reach—its troops occupied most of Guangzhou (formerly Canton) Province, just to the north of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong had been British territory since the nineteenth century. The colony consisted of the island of Hong Kong itself; on the mainland, a settlement on the Kowloon Peninsula; and, to the north of that, the scrubland of the New Territories up to the border with China. The island is about 16 kilometres across at its widest point and is separated from the mainland by Victoria Harbour and the Lye Mun Passage, which is about 500 metres across. The island and the Kowloon Peninsula are mountainous and the land is dominated by a number of very high peaks. A defensive line had been built along the border with China in the 1930s—it was called the Gin Drinkers Line since its western end lay on the shore of Gin Drinkers Bay. But almost everyone, including Winston Churchill, believed the island was indefensible and that any reinforcements sent there would be lost in the event of a Japanese attack.

When France surrendered to Germany in June 1940, the Japanese took the surrender as a signal to occupy French Indochina (Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam), and the British began to change their thinking on Hong Kong. Perhaps the territory might serve them well as a forward base for operations against the Japanese in southern China. Some commanders even thought that reinforcing Hong Kong might deter a Japanese attack. One of those men was Major-General Edward Grasset, a Canadian serving in the British army who visited Canada in August 1941. He was on his way back to the U.K. after his assignment as British military commander in Hong Kong had ended. Grasset discussed Hong Kong with H.D.G. “Harry” Crerar, an old classmate from RMC who was then Canada’s chief of the general staff. He convinced Crerar, and through Crerar the Canadian government, to agree to offer troops to reinforce Hong Kong if asked by the U.K. In mid-September 1941 that request was made and Canada agreed. A new formation, known as C Force, was authorized to be sent under command of Colonel J.K. Lawson, who was then director of military training. Lawson was promoted to brigadier.

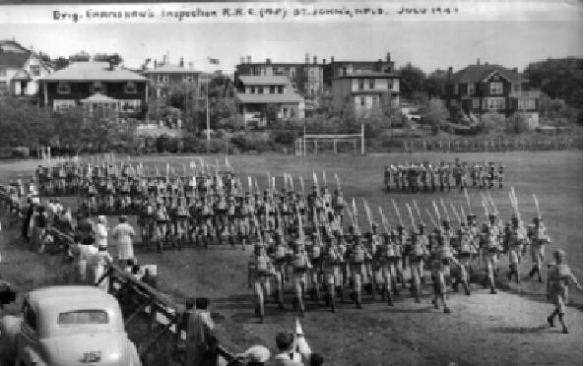

Crerar’s choice for the two battalions to form the core of C Force was the Royal Rifles of Canada, from Quebec City—also recently returned from garrison duty (in Newfoundland)—and the Winnipeg Grenadiers. He explained his preferences to the minister of national defence, J.L. Ralston, this way: “These units returned not long ago from duty in Newfoundland and Jamaica…The duties which they there carried out were not in many respects unlike the task which awaits the units to be sent to Hong Kong. The experience they have had will therefore be of no small value to them in their new role. Both units are of proven efficiency.” There were other reasons: assigning the two battalions to home defence might hurt unit morale, as the men had volunteered for active service and wanted to go; one unit was from the west and one from Quebec City, with a sizable francophone contingent of about 35 to 40 percent; and neither unit was well trained enough to go immediately to the U.K. to join the newly forming 4th Canadian Infantry Division (which was later converted to armour).

When the Grenadiers arrived back in Canada, many men who were sick of garrison duty and wanted to get to the U.K. as soon as possible applied for and received transfers, but some four hundred men signed up to replace them. No one was told the Grenadiers’ exact destination but recruits were informed that it would be a “semitropical” environment. Eventually the battalion was brought up to normal establishment of 835 men, with about 150 extra men for reinforcements. They were equipped with tropical clothing and footwear and sent by train to Vancouver, where they arrived on October 27, joining the Royal Rifles. Their ship, Awatea, left for Hong Kong that night accompanied by the converted liner HMCS Prince Robert. Aboard were all 1,937 men of C Force. Although some training was done aboard ship, the men who disembarked on November 16 and marched to the Sham Shui Po barracks in Kowloon were still nowhere near ready for combat. To make matters worse, the vehicles that were supposed to accompany them had arrived late in Vancouver and had been loaded onto a U.S. cargo ship, Don José. That ship was still at sea when war broke out on December 7 and was diverted to the Philippines.

The Grenadiers and the rest of C Force spent the first few weeks in Hong Kong settling in, drilling, and training. British Major-General C.M. Maltby, commander of the Hong Kong garrison, ordered most of the Canadians to occupy defensive positions on the southern perimeter of the island. The Grenadiers were allotted the southwest sector, though one company of Grenadiers was sent to help defend the Gin Drinkers Line. The line fell very quickly after the Japanese attacked on December 8 (December 7 in Hawaii) and the defenders were forced to withdraw to Kowloon. The Canadians helped to cover the withdrawal and were then pulled back to the island on the night of December 11. They then rejoined the rest of the battalion as part of West Brigade, a scratch formation that had just been pulled together. The brigade consisted of a mixed force of Canadian, British, and Indian troops and Hong Kong volunteers. The rest of the island was defended by East Brigade, another mixed force, commanded by British Brigadier C. Wallis.

On December 18 the Japanese crossed the Lye Mun Passage in small boats pulled by ferries under cover of heavy shellfire. The Indian colonial troops defending the coast were virtually wiped out. Then the Japanese launched four columns toward the centre of the island; they were supposed to converge at the Wong Ne Chong Gap, where Colonel Lawson’s headquarters for West Brigade was located. Like a relentless tide, the Japanese advanced across heavily forested steep hills and deep ravines. The Japanese knew that the Gap was the key to the island’s defences. Two important roads passed through it—one that connected Victoria Harbour, on the island’s north coast, to Repulse Bay and the town of Stanley on the south coast, and another that linked Aberdeen, in the southwest of the island, to the Ty Tam Tuk Reservoir to the east. If the Gap were to be taken, communications among the island’s defenders would be severely disrupted and it would be virtually impossible for either defending brigade to reinforce the other.

Lawson’s headquarters were in turmoil as the Japanese closed in. No one had any solid information on how many Japanese had landed on the island, where they had come ashore, or what direction the main body of their troops was heading in. The darkness of night was intensified by smoke from oil fires burning in Victoria, on the northern coast of the island. Japanese sympathizers and fifth columnists were cutting telephone wires to disrupt the defenders’ communications. Then it began to rain. When Lawson learned that two Japanese regiments were closing in on the summits of Jardine’s Lookout and Mount Butler, just to the east of the Gap, he ordered three platoons to stop the attackers. The platoons consisted of men from the Headquarters Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers under the command of Lieutenant G.A. Birkett. Birkett found it impossible to climb the high peaks to the east of the Gap in the rain and darkness and decided to wait until dawn. Then, outnumbered by about six to one, Birkett’s men advanced but were quickly pushed back, with two platoon commanders killed. Lawson then ordered his only reserve force, A Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, to attack.

The men of A Company were last seen climbing up through the rain and fog; most were never seen alive again. Survivors liberated from Japanese prison camps in August 1945 described how part of A Company, under Company Sergeant Major John Robert Osborn, captured the peak of Mount Butler with a bayonet charge.

Osborn, a forty-one-year-old veteran of the First World War, had served in the Hawke Battalion, a unit of the 63rd (Royal Navy) Infantry Division. He had been gassed, the effects of which affected his lungs for several years afterwards. At one point in the war he had also been captured by the Germans, and he was determined never to repeat the experience “under any circumstances.” Osborn had moved to Saskatchewan after the First World War; he had farmed for two years before settling in Winnipeg, where he married and had five children while working for the Canadian Pacific Railway. In 1933 he had joined the Winnipeg Grenadiers.

Osborn’s men held the peak of Mount Butler for three hours under constant rifle, machine-gun, and mortar fire. Casualties mounted. The Winnipeggers could not hold; they began to withdraw the way they had come, but ran into a Japanese ambush. The attackers closed in on the surrounded Canadians, throwing grenades. Osborn threw several of them back at the Japanese but could not reach one of them in time; he threw himself on it to protect his men and was killed instantly. Almost all the rest of the company were eventually killed also. When the handful of survivors were liberated after the war, they recounted the story of Osborn’s bravery and he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross—in effect, the first Canadian soldier of the Second World War to be so honoured.

Osborn’s futile defence gained but a few hours; by noon on the 19th Lawson’s HQ was overrun and he was killed in the fighting. The remains of D Company of the Grenadiers surrendered, but the rest of the battalion fought on under Sutcliffe’s command. The resistance put up by the remainder of the two Canadian battalions, the British and Indian troops, and the Hong Kong volunteers was brave, stubborn, and costly to the Japanese, but it was useless. No help was coming to Hong Kong from anywhere and casualties were mounting by the hour among both the defenders and the civilian population. And the Japanese were unrelenting—they pushed the remainder of the West Brigade back to a line between Victoria in the north and Aberdeen in the south, forced Wallis’s East Brigade to withdraw to the vicinity of Stanley Prison, and consolidated their hold on the island’s centre. On Christmas morning the Japanese contacted the island’s British governor, seeking a surrender. At first he refused, but Japanese attacks resumed on both fronts in the early afternoon and casualties among the defenders continued to mount. Maltby decided that the struggle was over and informed the governor that they must surrender. A white flag was hoisted over Maltby’s HQ and a small party was sent to Wallis, still holding out as OC East Brigade, to confirm the order to lay down arms.

All fighting ceased in the early hours of December 26. The killing, however, did not stop. In various parts of the island Japanese soldiers unleashed their wrath on the now helpless defenders, bayoneting and machine-gunning prisoners and slaughtering both wounded and medical staff in hospitals and aid posts. The Canadians were then imprisoned on the island and kept in appalling conditions—starved, deprived of medical supplies, and beaten. Before being shipped off to slave-labour camps in Japan, they were sometimes summarily executed. Of the 1,937 officers and men who left Canada in October 1941, 555 never returned, and many of those who did were so broken in body and spirit that they died prematurely in the years that followed.

The Winnipeg Grenadiers were reborn in Canada on January 10, 1942, and selected to join the 13th Canadian Infantry Brigade Group for the campaign to recapture Kiska Island in the Aleutian chain. It and Attu had been occupied by the Japanese in June 1942 as a diversion during the Battle of Midway. The landings took place on August 16, 1943, but Kiska was deserted—the Japanese had already pulled out. The Grenadiers remained in the Aleutians for four months before returning to Canada, then were sent to the U.K. as a training battalion in late May 1944. After the war the active service battalion was disbanded in 1946 but a reserve formation continued until 1965, when it was placed on the supplemental order of battle. Currently a cadet formation from Minto Barracks in Winnipeg perpetuates this brave but ill-fated regiment.