STRATEGY AND DOCTRINE

Since the 1991 Gulf War, the PLA’s strategy has been premised on preparing to fight local wars under conditions of informatization. Efforts have been focused on creating a PLA capable of winning a war against a higher technology adversary, unnamed but assumed to be the United States. Military analysts have carefully studied the performance of the U.S. military in the Gulf War, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq in an effort to understand American strengths and weaknesses.

The PLA’s active defense military doctrine is based on the three principles of nonlinear, noncontact, and asymmetric operations. Nonlinear operations entail launching attacks from multiple platforms in an unpredictable fashion, ranging across the enemy’s operational and strategic depth. Noncontact operations involve targeting enemy platforms and weapons systems with precise attacks from sufficiently far away to minimize the opponent’s ability to strike back. Asymmetric operations bring the PLA’s strengths to bear against the enemy’s weaknesses. For example, America’s heavy reliance on computer technology is considered to be its Achilles’ heel: successful interdiction of its computer network could destroy command and control functions. PLA literature also makes frequent mention of three types of warfare: media, psychological, and legal. In simplest form, these involve efforts to win over public opinion in the target country by convincing its civilians, and perhaps Chinese soldiers and civilians as well, of the justice of the PRC’s cause.

The PLAN has been tasked with a three-stage strategy. The first stage is to develop a force that can operate within the first island chain, stretching from Japan down through Taiwan and the Philippines. In the second stage, a regional naval force will operate beyond the first island chain to reach the second island chain, which includes Guam, Indonesia, and Australia. In the third stage, to be attained by midcentury, PLAN will constitute a global naval force.

Airpower expert Mark Stokes describes the PRC’s aerospace strategy as an integral component of firepower warfare involving the coordinated use of PLA Air Force (PLAAF) strike aviation assets, Second Artillery (Missile) Corps, conventional theater missiles, and information warfare. Although the military leadership seems to be developing a range of options for all levels of warfare, Stokes believes that the PLA is disposed toward a denial strategy that emphasizes operational paralysis in order to compel an adversary to comply with Beijing’s orders.

The PLA’s successful antisatellite (ASAT) test in January 2007 revealed its developing capabilities in space warfare. The test followed several years of discussion by PLA officers in defense journals and books of the need to have the ability to deny the use of space to others. While the authors differ somewhat in their suggestions, the need for secrecy is a common theme. The program should be “internally tense while [appearing] outwardly relaxed.” Having an orbiting network of concealed space weapons that can launch surprise attacks against U.S. assets fits in well with both the psychological component of the three-warfares doctrine and the need to practice asymmetric warfare.

China’s inventory of space-based intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, navigation, and communications satellites is being expanded. These share functions with the country’s commercial space program, allowing military uses to be downplayed. A navigation satellite was launched in 2009, and a full network of satellites is scheduled to provide global positioning for military and civilian users in the 2015–2020 time frame. Also launched in 2009 was the Yaogan, the sixth in China’s series of reconnaissance satellites sent into orbit since 2006. The development of the Long March V rocket, now delayed until 2014 owing to technical problems, will more than double the size of China’s current low earth orbit and geosynchronous orbit payloads. A newly constructed launch facility on Hainan will support these rockets. In addition to its ASAT program, the PLA is known to have at least one ground-based laser program.

With regard to nuclear weapons, China is believed to have at least 200 warheads, including 20 liquid-fueled intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) capable of reaching the United States, numerous other missiles with shorter ranges, and nuclear-armed submarines. The PRC has pledged a no-first-use policy, but from time to time, high-ranking figures have phrased this policy in ways that suggest the existence of unspecified caveats. It is not known, for example, whether demonstration strikes, high-altitude bursts, or strikes on what Beijing considers its own territory are included in the no-first-use policy. Recently, attention has focused on China’s proliferation activities, principally with regard to Iran and North Korea.

Training programs are designed to emphasize three strikes (sometimes translated as three attacks) and three defenses. The three strike targets are stealth aircraft, cruise missiles, and gunship helicopters. The three actions to defend against are precision strikes, electronic jamming, and reconnaissance and surveillance.

The PRC seems to be moving away from Deng Xiaoping’s advice of the early 1990s to “observe calmly, secure our position, cope with affairs calmly, hide our capabilities, and bide our time, be good at maintaining a low profile, and never claim leadership.” A growing point of view is that, while Deng’s advice may have been excellent when China was still weak, recent developments, including its rapidly expanding economy and military power, call for a more assertive strategy to secure China’s core interests. In 2010, the South China Sea was added to the list of China’s core interests, which have traditionally been focused on territories such as Tibet and Taiwan. A more assertive strategy also seems appropriate in light of the financial woes of the Western world and the perception that the United States, mired not only in financial difficulties but also in expensive, protracted conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, has entered a stage of rapid decline.

RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING

Aware that more technologically sophisticated military weapons will require better-educated and better-trained personnel to operate them, the PLA has made efforts to recruit university graduates, particularly those with science and engineering backgrounds, into the officer corps. Military academies also concentrate on producing technologically knowledgeable personnel, adapting their curricula to put more stress on science and technology.

In a national defense student program begun in 2001, the military offers training to those willing to join after graduation; in return, the students’ tuition is paid, and they receive a modest monthly living allowance. University graduation is followed by a year of formal training in a military academy. In the first year the program was offered, there were few takers, but when one-third of university graduates from the PRC’s newly expanded university system were unable to find jobs, incoming freshmen found the military option increasingly attractive.

Another priority is the noncommissioned officer corps. New recruits are now required to have at least high school diplomas, and the size of the corps is being expanded to constitute 40 percent of the army. The military as a whole now enjoys improved pay and benefits, as well as better creature comforts in the form of new barracks and karaoke clubs.

Consonant with PLA’s more outward-oriented stance, the navy and air force have in recent years received priority over the traditionally favored ground force. Though the ground force, at 64 percent of the total, is still by far the largest of the services, this is a drop from 73 percent in 1998. The navy now constitutes 14 percent of the total, up from 10 percent in 1998, and the air force has increased to 23 percent from 17 percent. These changes have been accompanied by proportional increases in budgetary allocations and weapons acquisitions. The ground force maintains an important role in protecting the country’s long land borders and in ensuring domestic stability as the Chinese population becomes more outspoken and increasingly prone to demonstrations and protests. In theory, keeping the domestic peace is the role of the People’s Armed Police (PAP), but the PAP has sometimes been judged unable to carry out its mandate effectively. According to credible reports, many of the personnel used to quell disturbances in Xinjiang in 2009 were PLA members who had been ordered to put on PAP uniforms because it would look less repressive to the foreign media.

The Outline of Military Training and Evaluation that became standard in the PLA in 2008 emphasizes realistic training conditions, training in complex electromagnetic and joint environments, integrating new and high technologies into the force structure, and amphibious warfare. Training exercises have become more sophisticated and are concentrated on achieving true jointness. In the past, different service arms typically converged in the same area but carried out their activities essentially separately. Service in a joint assignment is increasingly seen as a desideratum for those who aspire to be promoted to senior-level positions. The PLA recently established the Jinan Theater Joint Leadership Organization—the first of its kind—to integrate at the campaign level all services, including the Second Artillery Corps, the provincial leadership, and leading personnel from other organizations.

A National Defense Mobilization Law passed in 2010 gives the state the legal right to requisition civilian facilities and property. The new law, formalizing what would occur anyway, was presented in terms of its continuity with the Maoist People’s War and its emphasis on close military-civilian cooperation. In the post-Mao era, however, local governments have tended to resent the burden of supporting military units by supplying food, fuel, and financial contributions, thus necessitating a law that more clearly defines their obligations and responsibilities.

Also in 2010, PLAN ships carried out exercises in the Mediterranean that were described as unprecedented. The flotilla then visited the capital of Burma and cruised up the Irrawaddy River. A second group crossed the Coral Sea on a Pacific tour, visiting Tonga and Vanuatu.

Several exercises have been held in the South China Sea, presumably to signal to other countries Beijing’s determination to enforce its claim that this area constitutes one of the PRC’s core interests. In another 2010 exercise, all three of the navy’s fleets took part in a joint exercise that simulated the invasion of an island in the South China Sea controlled by another nation. Amphibious assault ships and tanks were used to land troops while countering electromagnetic interference and missiles fired by other troops posing as the enemy. To make the semiotics perfectly clear, the exercise was attended by almost 275 invited military attachés from seventy-five countries.

This kind of military theater generally has the desired effect and can be considered an operationalization of the three types of warfare—media, psychological, and legal. Domestic sources generally announce when such exercises will be held and explain why they constitute breakthroughs for the military. The stories are then picked up by foreign media, which, according to Western military experts, tend to amplify the exercises’ actual military significance. Another important motivation appears to be the desire to impress the Chinese public with the PLA’s increasing prowess and to take pride in its rapidly advancing capabilities.

The military has also diversified its training to include military operations other than war, including antiterrorism, emergency response, disaster relief, and international humanitarian operations. As of 2010, the PRC had seconded more than 2,100 personnel to U.N. peacekeeping operations. Although this was only one-fifth the number contributed by Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, it represents a significant change of attitude. In the past, China rejected peacekeeping missions as unwarranted interference in the domestic affairs of other countries. In 2010, China and the United Nations conducted a peacekeeping training class at the Ministry of National Defense in Beijing. Nineteen mid- to high-ranking PLA officers took part, and an accompanying press release declared that the information imparted would enable the PLA to further contribute to world peace.

As for antipiracy operations, a three-ship naval task force has been deployed on rotation in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Somalia since the end of 2008, marking the first time in its sixty-year history that the Chinese navy has conducted such operations. Military units also play an important part in domestic disaster relief operations following earthquakes and floods, and they have helped to quell ethnic unrest when the PAP was deemed inadequate to the task. Antiterrorism exercises have been conducted, sometimes in coordination with other members of the Shanghai Cooperative Organization, including Russia and several Central Asian states. These allow the PRC to cultivate an image of a responsible global actor while simultaneously accustoming its military to long-distance and long-endurance deployments. This experience enhances the PLA’s ability to protect China’s interests beyond national borders and to protect its access to the sea-lanes over which China’s commercial and energy imports and exports must move. There may be other potentially useful benefits: sources at the Indian defense ministry have complained that when its antipiracy vessels passed near those of China, the Chinese ships appeared to be probing the sonar capacities of the Indian naval vessels.

BUDGETS

Announced Chinese military spending has increased nearly twenty-five-fold, from 21.53 billion yuan in 1988 to 519.1 billion yuan in 2010. Even as other countries drastically cut back their military spending due to the end of the Cold War, the PRC’s defense budget increased by double digits each year until 2010—the one exception, a 9.6 percent increase announced for 2003, actually reached 11.72 percent by the end of the year. It is possible that the planned 7.5 percent increase for 2010 ended in double-digit figures as well. In any case, defense was one of the more generously treated sectors in the 2010 budget, which was intended to wean the country off a generous stimulus package enacted the year before to ease the impact of the global financial crisis. The PLA was promised that its budgetary allocations would increase as the economy recovered, which it has done.

While some of this largesse can be accounted for by inflation, increases also occurred in years when the inflation rate was small and even when the economy had slipped into deflation. Military budgets have slightly exceeded the increases in the PRC’s annual economic growth and are not believed to be so large as to place an undue burden on the economy as a whole.

Published defense budgets may not accurately reflect true military spending, which is estimated at two to three times the announced figure. Research and development for nuclear programs are not part of it, and payments for foreign weapons purchases come from the budget of the State Council; local areas are responsible for at least part of the costs of billeting troops. Finally, even accurate figures would not tell us how wisely the monies are spent. Procurement wastes are believed to be substantial. And, as in other sectors of the PRC’s economy, corruption is a serious problem.

WEAPONS

Funding for research and development in science and technology has greatly increased. In 2006, the State Council announced a National Medium- and Long-Term Program for Science and Technology 2006-2020, with the goal of transforming China into an innovation-oriented society by its end date. All the program’s key elements have military applications, including nanotechnology research; information technology; technology for the creation of new materials and for deep-sea operations; laser and aerospace technologies; radar; counterspace capabilities; secure command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR); high-resolution satellites; and manned spaceflight. Important advances in weaponry have been made through a combination of innovative research, purchases from foreign countries, reverse engineering, and espionage.

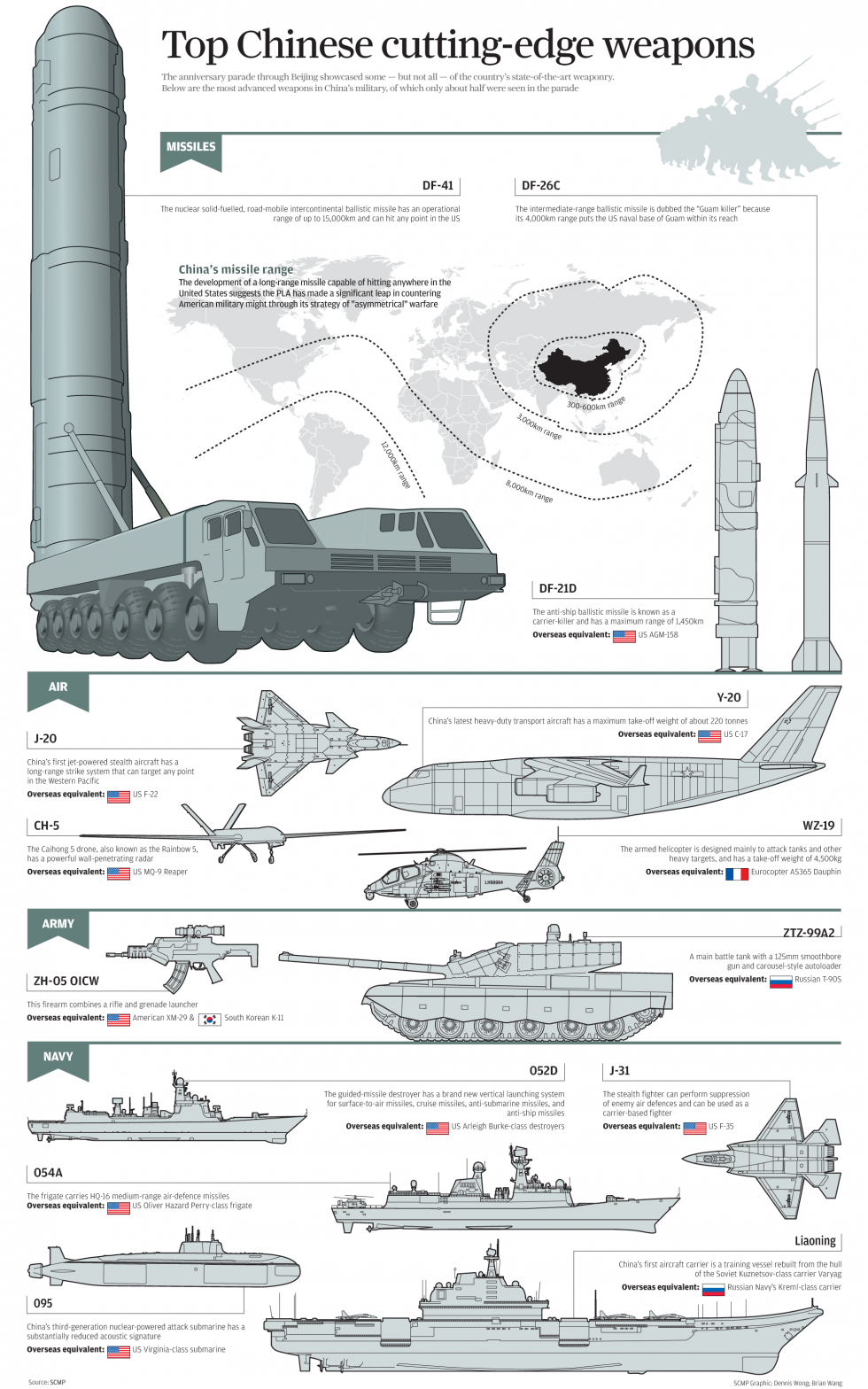

The U.S. Defense Department’s annual report on the military strength of the PRC notes that China has the most active land-based ballistic and cruise missile program in the world. It is developing and testing several new classes and variants of offensive missiles, creating additional missile units, qualitatively upgrading selected missile systems, and devising methods to counter opponents’ ballistic missile defenses. Missiles are becoming more accurate, more deadly, and more difficult to detect and evade. Of particular recent concern to foreign countries are the following:

• Aircraft carrier research and development program. China purchased the former Soviet carrier Varyag from Ukraine in 1998, towing it to a shipyard at Dalian and experimenting with improvements. The Soviet-era carrier is expected to be used for training purposes, and several indigenously produced carriers are scheduled to enter service in the 2015–2020 time frame. Negotiations with Moscow over purchasing Su-33 carrier-borne fighter planes were delayed by Russian concerns that the PRC would reverse-engineer the two planes it wanted to buy. The deployment of aircraft carrier battle groups would greatly expand the PRC’s strategic reach.

• Submarines. China has introduced four new classes of domestically designed and built submarines and now operates the largest submarine force among Asian countries. The second-generation Type 093/ Shang-class nuclear-powered attack submarine and Type 094/Jinclass nuclear-powered missile submarine have already entered service. Older Type 033/Romeo-class and Type 035/Ming-class diesel-electric submarines, which were based on 1950s-era Soviet technology, are gradually being replaced by the newer indigenous Type 039/Song class and Russian-built Kilo class. The even newer Yuan class has also entered batch production.

• Antiship ballistic missiles (ASBMs). China has now attained initial operating capability for an ASBM, a military milestone that most analysts regard as a game-changer for the military balance in Asia. Designated the DF-21 D, it is the world’s first weapons system capable of targeting a moving carrier strike group from long-range, land-based mobile launchers. This has important implications for the anti-access area denial strategy; it will enable the PRC to consolidate its claims to the South China Sea by preventing the United States from defending its Pacific allies.

• Stealth aircraft. The PLAAF’s fifth-generation fighter program achieved another breakthrough with the January 2011 test flight of the Chengdu J-20. Similar in design to America’s F-22 Raptor and Russia’s Sukhoi T-50 fighters, the plane has the potential to compete with the F-35, the most advanced fighter in the inventory of the U.S. Air Force. The J-20’s relatively large size indicates that it will have a long range and the ability to accommodate heavy weapon loads. Its ground clearance is higher than that of the F-22, which will facilitate loading larger weapons, including air-to-surface munitions. Newly developed air-to-ground weapons are required to be compatible with the J-20.

• Cyberattacks. The PRC has the world’s largest number of Internet users. Researchers based in Canada traced to China an electronic spying operation that penetrated computer networks in 103 countries. Among the sites entered were those of defense and foreign ministries, news media, private companies, political campaigns, and nongovernmental organizations. In some cases, information was exfiltrated; in others, the websites were defaced and data were destroyed or altered. Although a distinction is sometimes made between cyberespionage and cyberwarfare, the skills involved in intelligence gathering are the same as those involved in taking offensive action in wartime: the difference is what the keyboard operator does with, or to, the information after he or she has penetrated the network. American analysts were further disconcerted when a paper appeared in a Chinese scholarly journal detailing how a cascade-based attack could take down the U.S. power grid. Net attacks cannot be definitively linked to the Chinese government, and even assuming these attacks are perpetrated by “patriotic hackers,” we do not know whether the hackers are being cued by the Chinese government. Nonetheless, cyberattacks fit in with the asymmetric warfare that is part of the PRC’s military strategy. A worst-case scenario envisions a kind of technological Pearl Harbor in which U.S. command systems would be paralyzed and its major combat platforms destroyed by a sudden strike. Those who advance such a possibility point out that it is consonant with the traditional Chinese emphasis on strategic deception and surprise, as well as with current discussions of the topic in the PRC’s military journals.