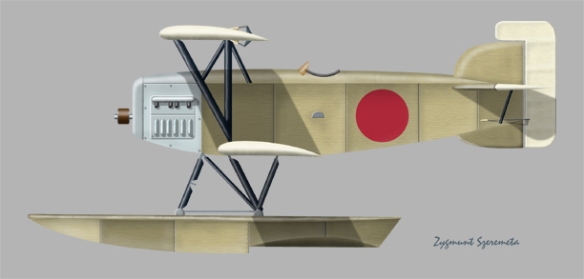

Heinkel HD.26, One of two HD.26 owned by Japanese, it was powered with Hispano-Suiza engine.

The benefits arising from the sudden flush of government money made available by the Ruhr crisis, and the further deterioration of the effectiveness of the Control Commission were not confined to the Reischswehr, but spread to the skeleton of the German navy, enabling the bones to be covered with a defensive skin if not full sinews. A naval captain named Lohmann was entrusted with $2 ½ million, for which no account needed to be rendered. Captain Lohmann funneled part of the money to the Travernünder Yachthafen, A.G., and ordered prototypes and testing of small, fast motorboats capable of firing torpedoes. Lohmann spent more money to subsidize a Dutch firm in The Hague, Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw (I.v.S.), where foreign orders for five-and six-hundred-ton submarines were obtained — especially from Japan, Turkey, Spain and Finland. Although none of the U-boats was destined for the German navy, the experiment in Holland enabled German engineers to keep up with current developments by studying the latest design and construction techniques.

The ten Heinkel seaplane fighters authorized for purchase at the same time money was provided for the Reichswehr’s far larger number of Fokker D.XIIIs, which were being built in the Swedish branch factory, accrued to the navy free and clear. To provide training for crews to man these airplanes, and for others Lohmann planned to buy in the future, a cover organization was created with offices in Berlin and facilities in Warnemünde. Known as Severa, Ltd. (short for Seeflugzeug-Versuchsah-teilung, Seaplane Experimental Testing Service), the bogus firm was allotted three hundred thousand dollars a year for operating expenses. Severa was ostensibly created to provide aerial target-towing for the navy’s antiaircraft gunners, but Lohmann combined this activity with pilot and observer training, turning out six of each during the first year. Spending more money, Lohmann acquired the Caspar works at Travemünde, and opened a flying training school at List, on the island of Sylt, near the Danish border. Classes were upped to twenty-seven cadets, enrolling for a two-year curriculum. The Japanese, who, more than any others, manifested continuing interest in German naval aviation developments, followed Lohmann’s progress throughout; and it was the Japanese military attaché, Captain Komaki, who informed Lohmann that he was not really putting anything over on the Allies. In February 1925, Komaki paid a visit to Naval Command and reported that the Control Commission “was doubtless well informed about the construction of airplanes at Warnemünde and Copenhagen, especially since the British had an extensive espionage service in Germany.” Komaki’s remarks were delivered only a short time after the Commission’s so-called general inspection had ended, at a time when that body’s effectiveness was ebbing fast, and in any event, whether informed or not, the British made no decisive moves to halt the production of warplanes or cancel the training of naval flyers. (Nor did the French; however, the British later admitted that they did not pass along all of their intelligence to France at the highest government levels.)

While Komaki was reporting his findings in Berlin, his naval counterpart, Captain Kojima, was at Warnemünde with a contract for Ernst Heinkel. What Kojima wanted was a launching device that could hurl a reconnaissance plane from the forward section of the new thirty-thousand-ton Japanese battleship Nagato. Kojima had brought along an enlarged photograph of the new dreadnought, mounting sixteen-inch guns, and he pointed to a clear space forward of the bridge and on top of the massive turret. Here, the Japanese said, is where the plane will be carried and from where it must be launched. He explained that the floatplane would have to be clearly airborne within a sixty-foot run. Heinkel tackled the problem with typical energy, and within ninety days was ready for testing. Manufacturing the two floatplanes — the two-seater He.25 and the single-seater He.26 — had been easy enough, but no engines were available in Germany that would provide the necessary takeoff acceleration. Through a Dutch company, however, he easily purchased two new British-made Napier-Lion aircraft power plants of 300 and 450 horsepower. The launching device was simple in theory, simple in construction. Heinkel built iron rails on a wooden girder. On top of the girder rested a small, lightweight trolley. Resting on the trolley was the plane itself. With the pilot strapped in the cockpit, and with the launching rails turned into the wind, the plane was braked while the engine was started and run up to full rpm. With the tachometer needle holding steady just at the edge of the red line, the pilot signaled go, the plane was unbraked, and the sheer acceleration provided by the propellor chewing and pulling through the air started the trolley whizzing on its wheels down the rails. At the end of the run the plane had achieved flying speed and rose into the air, while the trolley merely flipped off the end of the rails.

The Warnemünde test was a success, but Heinkel was invited to Japan to demonstrate that the device would work aboard the Nagato, and at sea. Heinkel was piped aboard the great ship where he “was received like an admiral, with six hundred Japanese sailors in snow-white uniforms paraded on deck.” His launching rails had been anchored to the top of the number two turret, and could be turned through about sixty degrees. In September 1925, the Nagato put out of Yokosuka and stood for the open sea. Heinkel was invited to the flying bridge to see that the great prow was pointed dead into the wind, and watched his company pilot, Bücker, climb into the He.26 and prepare for launch. The Napier-Lion roared into life and held. Freed, the biplane shot forward and was airborne into a freshening wind before reaching the end of rails. “She flew over the foc’s’le of the Nagato, and away,” Heinkel remembered. “Bücker then circled the ship while the whole crew cheered.”

Heinkel was back in Germany in time to oversee his company’s entry in Germany’s first large-scale seaplane competition, sponsored by the Cavil Air Transportation Association, but in reality backed by the German Naval Command. The competition was for the purpose of selecting the finest aircraft possible for the navy’s armed reconnaissance role, that is, a combat plane to be built in open violation of the Versailles Treaty, whose clauses forbidding the construction of military planes had in no way been affected by the 1926 Paris Air Agreements. By early summer of that year, seventeen different designs had been readied to compete for prize money totaling ninety thousand dollars and the almost certain guarantee of contracts for series production that would follow. By June 24, when the competition began, seven of the designs had been withdrawn, and in the speed heats that followed, Heinkel’s He.5a and He.5b took first and second place, with speeds of 130 miles per hour. Although the He.5s were new designs, three-seater monoplanes, Heinkel again had to rely on foreign engines, including the Napier-Lion and a 420-horsepower French Gnome-Rhone. The seaworthiness tests were held near Warnemünde on August 5, and Heinkel watched angrily as one of his pilots, Dewitz, in an attempt to make what he described as an “elegant and classy” landing, smacked the water flat, crushed the floats, and managed to get rammed by the rescue launch, which caused the He.5 to capsize and sink. The other floatplane, flown by Wolfgang von Gronau, made a gentle splash onto the surface of the water by stalling in from a few feet in a nose-high altitude. Heinkel took first and third place, while Junkers placed second with his W.33, a seaborne descendant of his famous F.13.

So successful were the German navy’s beginnings at resurrecting its air arm that the higher echelon could afford to turn down every Russian offer of cooperation. The Soviets offered to help train navel pilots at their base in Odessa, by the warm waters of the Black Sea, where flying conditions in the winter and during the early spring were far better than those prevailing on the Baltic, but the offer was refused. The German Chief of Naval Service, Admiral Hans Zenker, stated in an official memorandum dated July 22, 1926, that “military cooperation with Russia could only be undertaken with great caution … [but] the thread [was] not to be cut, so as to be able to put pressure on the Anglo-Saxons occasionally.” One of Zenker’s subordinates, Captain Wilfried von Loewenfeld, expressed the majority opinion of the traditionally conservative navy when he said: “Britain is at the moment the leader of Western culture, and if she is destroyed by communism, or by a revolt of her colonies, the danger of the Bolshevization of Europe becomes burningly acute.” Loewenfeld urged, above all, a gradual understanding with Great Britain — an understanding that could never come to pass if the German navy openly began cooperating with the Russians. To Loewenfeld and Zenker, what the Reichswehr did was not the navy’s concern. The captain’s advice to Zenker as to how best to handle the Bolsheviks was worthy of the French. “Only play with the Russians,” he suggested. “Deceive them amicably, without their noticing it.” In the years that followed, almost all that the German navy was willing to give the Russians were plans for obsolete submarines.