Now converted to Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz’s policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, Holtzendorff produced a memorandum of December 22, 1916, based on statistics and projections from a group of economic experts (Department B1). The report, which predicted the demise of Britain by unrestricted submarine warfare, held that wheat imports were the Achilles’ heel of the British economy and estimated that in December 1916 Britain had but 15 weeks of wheat remaining. Holtzendorff held that if during the first two months of unrestricted submarine warfare the Germans could sink 600,000 tons of shipping a month and about 500,000 tons each of the next four months, the tonnage available for food imports would decline by an “irreplaceable” 40 percent. Britain would be starved into surrender.

Holtzendorff and Tirpitz recognized that a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare would likely bring the United States into the war, but they were also convinced that they could knock Britain out of the war before U.S. military assets could be made to count. They also denigrated U.S. military capability. German U-boats would prevent the Americans from sending troops to Europe. Holtzendorff reportedly told the kaiser, “I give your Majesty my word as an officer, that not one American will land on the continent.” Warnings from German envoys in neutral countries that an unrestricted submarine warfare campaign would cause these countries to curtail food shipments to Germany were dismissed as “defeatist rubbish.”

German Army chief of staff Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and first quartermaster general of the army General of Infantry Erich Ludendorff supported Holtzendorff’s view, overcoming the arguments against it advanced by Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg and Foreign Minister Gottlieb von Jagow, both of whom hoped for a negotiated peace. On January 9, 1917, the government decided that an unrestricted campaign would begin on February 1. This decision was announced on January 31.

The predicted diplomatic consequences of launching the new unrestricted campaign were not long in coming. On February 3, 1917, President Wilson severed diplomatic relations with Germany. The Zimmermann Telegram—containing a proposal for a German-Mexican and even a German-Japanese alliance against the United States—also surfaced, exacerbating tensions between the two nations. A series of almost inevitable sinkings of U.S. vessels carrying American citizens as passengers hastened matters, and on April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany.

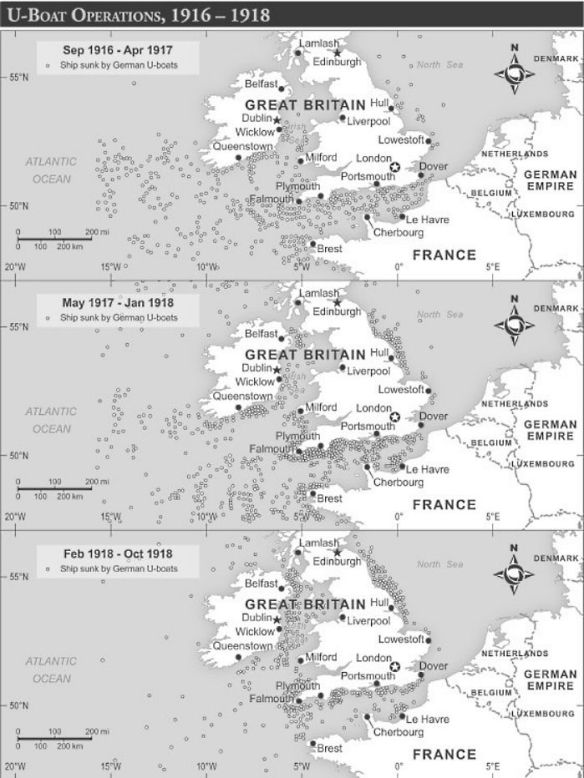

The renewal of the German unrestricted submarine warfare campaign commenced on schedule, with some 120 U-boats deployed. Shipping losses rose dramatically to 520,412 tons in February, 564,497 tons in March, and 860,334 tons in April, at the cost of only 9 U-boats. From this peak, shipping losses fell to 616,316 tons in May and 696,725 tons in June. As the British gradually expanded the scope of convoy from mid-May, losses declined still further to 555,514 tons in July, 472,372 tons in August, 353,602 tons in September, 466,542 tons in October, 302,599 tons in November, and 411,766 tons in December. Forty-three U-boats were sunk in the same six-month period, more than three times the number lost in the first six months of the year.

During the first six months of 1918, U-boats sank more than 1.8 million tons of shipping and a further 889,442 tons up to the armistice on November 11. German losses were high, with more than 120 U-boats sunk. Furthermore, as the U-boats sought out weak links—areas in which ships sailed without the benefit of convoy—the Allies extended the scope of the system until the vast majority of shipping was covered. The German unrestricted submarine campaign against shipping had not only failed but had also, by forcing the United States into the war, cost Germany victory. The U-boats were not able to interrupt the flow of American troops to Europe, despite Holtzendorff’s pledge to the kaiser. All damage inflicted by U-boats to the transport fleet was done in European waters. Six transports were sunk, 4 of them on the home voyage, but the total loss was fewer than 300 lives. U.S. forces were thus able to intervene in sufficient numbers in time to affect the outcome.

The small number of Austrian submarines in operational service at the beginning of the war and their limited range effectively confined their use to the Adriatic. After France declared war on Austria-Hungary on August 13, 1914, elements of its Mediterranean fleet commenced operations in the Adriatic, conducting sweeps with heavy ships and undertaking minor landings, all in the hope of influencing Italy to join the Allies. Austrian submarines always were a threat that became a reality on December 21, when its U-12 torpedoed the French flagship dreadnought Jean Bart without, however, sinking it. This incident convinced the French to give up offensive operations in the Adriatic and focus on a distant blockade of the Strait of Otranto.

In the period leading to the entry of Italy into the war on the Allied side, the French moved their blockading squadron farther north into the Adriatic. Ship-of-the-Line Lieutenant Georg Ritter von Trapp, commanding the U-5, succeeded on the night of April 26, 1915, in torpedoing and sinking the French armored cruiser Léon Gambetta with heavy loss of life, demonstrating once again the vulnerability of surface vessels in these confined waters. After Italy entered the war in May, the situation remained much the same. In the face of the threat posed by submarines, heavy ships could not operate effectively in the Adriatic, and operations became largely a quasi-guerrilla war in which the Austrian submarines, reinforced by small German U-boats transferred overland, played a major role.

Germany began transferring submarines to the Mediterranean theater in May 1915 when it became clear that the limited Austrian submarine force could do little to affect operations in the area, despite their effectiveness in the Adriatic. These U-boats had considerable success on arrival. Captain Lieutenant Otto Hersing’s U-21 torpedoed and sank the British predreadnought battleship Triumph at the Dardanelles on May 25 and sent to the bottom another British battleship, the Majestic, two days later. Two smaller submarines, however, proved much less effective, and subsequent German submarine operations during the Dardanelles Campaign were largely inconsequential.

The German Navy continued to send U-boats to the Mediterranean, dispatching the smaller boats overland by rail for assembly at Pola and passing the larger boats through the Strait of Gibraltar. One early arrival, Lieutenant Heino von Heimburg’s UB-15, sank the Italian submarine Medusa in the Adriatic on June 1, 1915. On July 7 Heimburg, now commanding the UB-14, sank the Italian armored cruiser Amalfi before sailing into the Mediterranean.

The Mediterranean theater was attractive because there were clearly defined choke points through which much traffic had to pass. The Mediterranean was also obviously crucial for French and Italian ship traffic, and much British shipping also sailed through the sea before or after transiting the Suez Canal. The weather also permitted operations during the autumn and winter when it could hamper Atlantic operations, and operations there were also far less likely to acerbate tensions with the United States, since fewer U.S. ships or American passengers sailed in that sea.

The German submarine campaign in the Mediterranean began in earnest in October 1915. The submarines used Austrian bases at Pola and Cattaro for their operations. During this month five large U-boats sank 63,848 tons of shipping, more than three-quarters of all merchant vessel sinkings in all theaters combined. More large and small boats reinforced the Mediterranean flotilla, with merchant shipping losses reaching 152,882 tons in November and 76,693 tons in December.

During 1916 the Central Powers’ U-boat campaign in the Mediterranean continued to enjoy success. The first quarter of the year saw Allied shipping losses decline as the U-boats underwent refits, contended with winter weather conditions, and were subject to the restrictions on attacking passenger liners. Nevertheless, losses were high enough to lead the Allies to strengthen their patrol systems and divert as much shipping as possible from sailing through the Mediterranean, even though this extended voyages and tied up vessel capacity. New U-boats arriving from Germany and existing boats returning to service pushed merchant shipping losses for the second quarter of 1916 in the Mediterranean to 192,225 tons, about half of all losses in all theaters. These successes continued into the summer and autumn as German U-boats sank 321,542 tons of shipping between July and September. Nor was there any real relief in the autumn and early winter, since a further 427,999 tons of shipping went down by the end of the year. In aggregate, German U-boats sank well over 1 million tons of shipping in the Mediterranean during 1916 while losing only two submarines, one of which sank after running into one of its own mines.

The year 1917 brought the illusion of calm, for most of the German U-boats were refitting. Losses fell to 78,541 tons in January before rising again to 105,670 tons in February and then dropping to 61,917 tons in March. The Germans reinforced their Mediterranean flotilla, and new Austrian boats, based on the German UB-II class, joined the German submarines in operations in the central Mediterranean. Together they sank 277,948 tons of shipping in April. The Allies were then forced to reappraise their system of trade protection and began introducing the convoying of merchant shipping in late May, whereupon losses fell to 180,896 tons in May and 170,473 tons in June. Even though the Germans increased their U-boat force by more than 25 percent, losses continued to decline in July and August to 107,303 tons and 118,372 tons, respectively. An unprofitable diversion of U-boats in the autumn to support operations in Syria against the Allied offensive netted a few small warships but relieved the pressure on merchant shipping. Success returned when the U-boats resumed their effort against merchant shipping in December, with losses rising to 148,331 tons. Once again, Germany’s total U-boat loss for the year was two boats, while the German and Austrian submarines sank well over 1.25 million tons of shipping.

The year 1918 saw Allied efforts to protect trade bear fruit. During the first six months of the year German and Austrian submarines sank about 600,000 tons of shipping, but their losses rose to 10 boats, twice the total in the three previous years of operations. Submarine successes fell dramatically in the months before the armistice; they sank fewer than 250,000 tons of shipping and lost a further 4 boats in the process. Moreover, these diminished accomplishments came about despite the fact that almost twice as many submarines were operational as in 1917.

Between 1915 and 1917 the German Navy also operated a small number of submarines in the Black Sea. The first boats arrived in May 1915 as part of Germany’s support for Turkey during the Dardanelles Campaign. Most of the boats deployed were small UB- or UC-type coastal submarines, and success was limited, although their operations did cause the Russians to deploy their own hunting squadrons of destroyers. The few larger submarines dispatched to the Black Sea had no greater success. In all, Germany sent three large and about a dozen small submarines to the Black Sea and lost almost half of them, chiefly to mines.

Overall, the most important campaign in which the submarines of the Central Powers engaged—their operations against merchant shipping—came close to total success in April 1917, only to fail completely to overcome the effectiveness of the convoy system. In the process, however, the Central Powers permanently redefined the place of the submarine in warfare.

Further Reading

Abbatiello, John. Anti-Submarine Warfare in World War I: British Naval Aviation and the Defeat of the U-Boats. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Fayle, C. Ernest. Seaborne Trade. 3 vols. London: Murray, 1920–1924.

Gardiner, Robert, and Randal Gray, eds. Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1985.

Gibson, Richard H., and Maurice Prendergast. The German Submarine War, 1914–1918. New York: Richard Smith, 1931.

Halpern, Paul G. A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994.

Herwig, Holger H. “Luxury” Fleet: The Imperial German Navy, 1888–1918. London: Allen and Unwin, 1980.

Sokol, Anthony E. The Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1968.