Evoking the heritage of the revolutionary defence of the nation, Hugo declared, ‘Let the lion of 1792 draw itself up and bristle’ as the Government of National Defence committed itself to continuing the war. A proclamation drawn up by the 32-year-old Gambetta, who was minister of both the interior and war, blamed defeat on ‘twenty years of corrupting power which quashed all the sources of greatness’. Others sought different scapegoats. The church pointed at the moral degeneracy of the Empire. In the Dordogne, peasants rounded on local nobles, burning one young aristocrat to death.

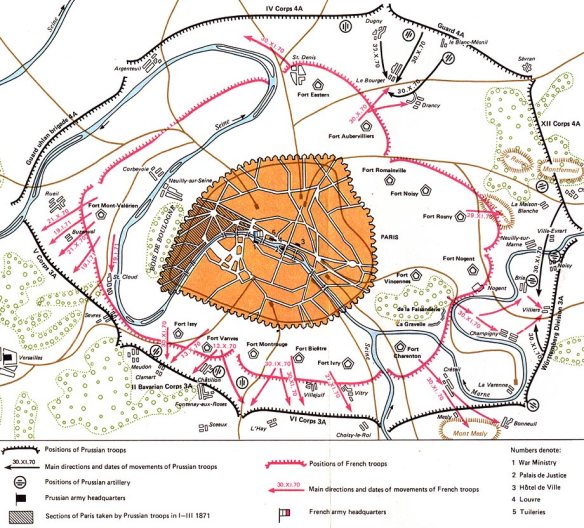

Gambetta’s proclamation urged the French to raise their spirits to fight on. But the Germans rolled over northern France and surrounded Paris with a quarter of a million troops.

Most of France’s army had either been captured by the Germans or was bottled up in the east where the 160,000-strong force in Metz surrendered at the end of October. The country’s heart was not in continuing the war. Gambetta, who flew out of Paris by hot-air balloon to direct the action from Tours, struggled to assert authority over local leaders seeking autonomy for their cities, particularly in Marseilles. The National Assembly decamped to Bordeaux.

The ring of ten-metre high fortifications built round the capital by Thiers in 1840 and since reinforced meant that besiegers had to cover a fifty-mile front, from which they kept up a constant bombardment though it did relatively little damage. The defenders numbered 50,000 professional soldiers plus 90,000 Gardes Mobiles conscripts, 15,000 men from the navy and 8,000 police and firemen. The Paris National Guard was 300,000 strong, but many were ill trained, undisciplined and no match for the invaders.

The siege, from 19 September 1870 to 28 January 1871, cut off manufacturers from national and foreign markets. The Germans severed the telegraph lines. To provide food, 250,000 sheep and 40,000 oxen had been brought in to graze in the Bois de Boulogne, but supplies eventually ran short and people turned to other sources of sustenance. Horses were the first to be consumed including two trotters given by the Tsar to Napoleon III. Dogs came next. Then it was rats served in pies at the Jockey Club. The rich ate meat from slaughtered zoo animals; the Café Voisin on the rue Saint-Honoré served a Christmas Eve dinner that included stuffed donkey’s head, elephant consommé, bear ribs in pepper sauce, roast cat with rats and truffled antelope terrine, accompanied by the finest clarets and a 1858 Burgundy.

Sixty-five hot-air balloons flew out of the city with a total of 164 passengers and five dogs; none managed the flight back. Instead, carrier pigeons were used to carry messages from Tours – a microphotography unit there reduced pages to tiny sizes; a pigeon could carry thousands, which were projected on to a screen in Paris and transcribed, but only fifty-nine of the 302 birds from the Loire Valley arrived, some brought down on the way by German falcons.

The ministry of works forged guns in basements on the rue de Rivoli and invented prototypes of weapons that would come into use in the following century. Proposals put forward to the scientific committee but never brought to fruition included petroleum bombs to explode above the enemy, shells containing smallpox germs, a ‘mobile rampart’ much like a tank and a unit of women fighters in black pantaloons with orange stripes, hooded black blouses and black képis; they would hold out their hands to the enemy and kill them with embedded pins laced with Prussic acid.

Touring Europe to meet the foreign ministers of Russia, Austria and Britain, Thiers found none ready to back France. So he went to see Bismarck who demanded the ceding of all of Alsace and parts of Lorraine as well as large reparations. The government decided to fight on. The French won a victory near Orléans in mid-November but an attempt to break out of the capital at the end of the month went badly wrong with 4,000 casualties compared to 1,700 for the Germans.

The political orator and anti-Bonapartist, Jules Favre, led fresh negotiations with Bismarck at the Rothschild château at Ferrières*. The French hoped that by offering a large monetary indemnity they would be spared from territorial losses. But the Prussian was unyielding: ‘We will talk about the money later, first we want to determine the frontier,’ he said. His position was strengthened by four victories in the winter of 1870–1, as severe cold gripped the capital. Famine threatened. Coal, wood and medicines were in short supply.

The victors rubbed salt into French wounds with the declaration of the German Empire under Wilhelm I in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles in January 1871, while acrimonious negotiations continued over territory and money with bitter sessions between Bismarck and Thiers who called in James de Rothschild to help, only for the banker to be subject to a tirade from the Prussian. ‘Count Bismarck would seem to have conducted himself with monstrous brusquerie and intentional rudeness,’ the German banker Gerson von Bleichröder noted. The treaty was finally signed on 26 February, providing for an indemnity of 5 billion francs and the loss of Alsace and part of Lorraine.

The government, now in Bordeaux, provisionally accepted Bismarck’s terms, and got a stipulation that Paris would not be occupied and that regular soldiers would not be taken prisoner. German troops entered the capital only for a victory parade in the Bois de Boulogne and a review by their new emperor on the Champs-Élysées; they did not stay long but it was still a stinging humiliation. The drama now unfolded among the French, once again pitting the two sides descended from the Revolution against one another.

Wednesday, 8 February 1871. A general election returned a large number of conservative, rural and middle-class deputies with twice as many royalists as republicans. Hugo and Gambetta refused to take their seats in protest at the loss of Alsace and a chunk of Lorraine where inhabitants were given until October 1872 to decide whether to stay and accept German nationality or to move to French territory with only what they could carry. Patriots lamented the lost lands, with the poet Victor de Laprade urging his compatriots to ‘foreswear pity [and] cultivate hatred to the limits’. But only 10 per cent of the population chose to leave.

Friday, 17 February. The new parliament named Thiers as the chief executive of the Republic to restore peace and order. Exhausted, feverish and unable to work with Thiers, Gambetta left for Spain. Once again, Paris was out of step with the nation. At the election, it gave thirty-seven of its forty-two seats to republicans and socialists, among them Louis Blanc, the consumptive old Jacobin Louis Charles Delescluze and Félix Pyat who edited the newspaper Le Combat. Blanqui denounced the government and the moderate mayor of Paris, Jules Ferry, for failing to emulate the resistance spirit of revolutionaries of 1792. Riding the wave of electoral success, radicals staged a string of demonstrations calling for a ‘democratic and social republic’ and the arming of civilians. Marches, in January 1871, ended with shots being exchanged and the arrest of eighty left-wingers. The National Guard, which had played a prominent role in past turbulence in the capital, had not been disarmed by the armistice because the Germans thought it would maintain stability. This proved to be a major misjudgement since the force reflected the capital’s radical nature.

Delegates chosen by its 260 battalions elected as their chief the Italian revolutionary, Garibaldi, who declined the post. They created a thirty-eight-member central committee with headquarters near the Place de la Bastille in the area that had been the scene of recurrent revolts earlier in the century. Its first act was to refuse to recognise the authority of the military governor of Paris or of the National Guard commander appointed by the government, which had set up in Versailles. Ferry left for Versailles.

Saturday, 18 March. The Guard clashed with regular soldiers trying to take from them a stock of obsolete bronze cannons set up in the city’s parks. On the Butte Montmartre, where 170 of the cannons were located, the confrontation escalated despite attempts to mediate by the local mayor, Georges Clemenceau. Two generals were seized by the National Guard and shot dead. Barricades went up in workers’ districts. The army withdrew. In Versailles, Thiers denounced ‘an open revolt against national sovereignty’.

In the following days, the National Guard took the Hôtel de Ville, hoisting the red flag. It occupied ministries and police headquarters while Blanquists seized gunpowder stored in the Panthéon and the Gare d’Orléans railway station. Thiers and the government were joined by 40,000 soldiers and Marshal Patrice de MacMahon, the commander of imperial forces who had just been released from captivity in Germany. A delegation led by Clemenceau went to present Thiers with proposals for Paris to gain independent status, but was rebuffed. Relations between the radicals and the district mayors in the capital rapidly deteriorated. Guardsmen seized Clemenceau’s office – ‘we are caught between two bands of crazy people, those sitting in Versailles and those in Paris,’ he remarked.

Sunday, 26 March. Elections for a Commune council, with an all-male franchise, returned a radical majority. Though in prison in Brittany, Blanqui won in several arrondissements. Abstention was high in smart districts. The council’s membership, reduced from ninety-two to sixty as a number of successful candidates refused to take their seats, included a majority of industrial and office workers who saw themselves picking up the strands of 1848 in what a song termed ‘cherry time’.

The council got down to work on a list of long-standing left-wing aspirations, deliberating in secret so as to give nothing away to the authorities in Versailles. It had no president though the absent Blanqui was elected honorary chief. There was some pragmatism. The gold reserves of the Bank of France were protected to ensure that the National Guardsmen were paid. A loan was raised from the Rothschild bank. Publication of pro-Versailles newspapers was banned, but the most popular daily, Le Rappel, was not censored when it condemned the killing of the two generals.

Still, the new regime in the city was distinctly radical. Night work was abolished in bakeries. A rent holiday was decreed for the period of the siege. Pawned tools and household items were to be returned free. Commercial debt obligations were postponed with interest waived; employees got the right to take over firms deserted by owners who were, however, guaranteed compensation; workers set up schools and orphanages with free food and clothing and took over local administration.

The red flag replaced the tricolour. The death penalty was abolished. The Revolutionary calendar was restored. The Commune council separated church and state; religious property was taken over and religious education banned in schools. Churches were required to be open for public political meetings in the evening. A series of measures laid the foundations for municipal government catering for the mass of the population, creating a heritage for left-wing local urban government in the future.

Though they had not been given the vote, a number of women figured prominently in the Commune, most famously Louise Michel, the ‘Red Virgin’ of Montmartre. A women’s union called for gender equality, the right of divorce, professional education for girls and the abolition of prostitution. The anarchist Nathalie Lemel set up a cooperative restaurant serving free food for the poor. A Russian exile, Anne Jaclard, founded a newspaper, Paris Commune. A female battalion was formed in the National Guard.

Sunday 2 April. Regular forces under MacMahon deployed on the outskirts of the capital, their ranks swollen by prisoners of war released by the Germans after the peace treaty was finalised in Frankfurt. They turned back the National Guard in a skirmish at the Pont de Neuilly after which four guardsmen were summarily shot. Undeterred, the Commune council launched an offensive against Versailles, but the guardsmen were caught in crossfire and fled back to the capital in disarray. Communes in Marseilles, Grenoble, Lyons, Narbonne and Limoges were crushed.

Monday 3 to Wednesday 5 April. The Commune council adopted tougher policies, including a decree by which anyone accused of complicity with the Versailles government could be immediately arrested, imprisoned, and tried by a special jury. If convicted, they would become ‘hostages of the people of Paris’ and every execution of a Communard by the opposing forces would be followed immediately by the execution of three times as many hostages. The first arrests were of the archbishop of Paris and two hundred priests, nuns and monks. Versailles rejected a proposal to barter Blanqui for seventy hostages and passed legislation allowing military tribunals to mete out punishment within twenty-four hours.

A Committee of Public Safety, modelled on Robespierre’s group, was created with the newspaper editor Félix Pyat in a prominent role. It widened the net of arrests, taking in an eighty-year-old general and recent commanders of the National Guard. Following a suggestion by the painter Courbet, backed by Pyat, Napoleon’s column in the Place Vendôme was destroyed for a second time as ‘a monument of barbarism’; the idea was to replace it with a monument made of melted-down German cannons. Thiers’s home was ransacked and demolished; proceeds from the sale of the furniture went to widows and orphans. ‘The hour of revolutionary war has struck,’ a Commune leader declared. ‘To arms, citizens! To arms!’ But there was no concealing the weakness of Paris. A fifth of guardsmen were absent without leave. Desertion more than halved the ranks of trained artillerymen.

The night of Friday 7 to Saturday 8 April. A key position south of the capital, Fort Issy, was taken by the army after a see-saw battle; the National Guard commander was sacked as a result and replaced by a journalist without military experience. Many of the troops were smarting from defeat and captivity at the hands of the Germans. Drawn predominantly from conservative rural areas, they were told by their commanders they faced a radical anti-religious rabble of agitators, work-shy ruffians, criminals and foreigners, who did not have the support of the mass of Parisians and would consign the nation to the devil.

Sunday 21 May. Sixty thousand soldiers moved through an undefended section of the fortifications to occupy the Passy and Auteuil districts before taking key points and fighting an artillery duel between the Quai d’Orsay, the Madeleine and the Tuileries. Haussmann’s boulevards helped to circumvent barricades and soldiers fired from vantage points on top of the Second Empire’s apartment blocks. As in 1848, there was no quarter. Sixteen National Guardsmen captured on the Left Bank were summarily shot; Communards carrying away dead and wounded were peppered with bullets. After a fierce battle at the Madeleine, 300 Communards were caught and shot on the spot. Defiant, the committee of public safety declared that ‘Paris, with its barricades, is undefeatable’. But only some 15–20,000 people responded to the call to arms.

Monday 22 May. As fighting swirled in the streets, National Guardsmen burned down the Tuileries Palace after soaking the walls and floors with oil and turpentine, and putting barrels of gunpowder at the foot of the grand staircase and in the courtyard. The 48-hour fire gutted most of the huge edifice. Communards set fire to public buildings along the rue Royale, the Faubourg-Saint-Honoré and other central streets; the Louvre library was destroyed by flames, though the museum was saved.

Tuesday 23 May. Having established itself in central Paris, the army headed for Montmartre and its hill, the Butte, overcoming the women’s battalion on the way. The soldiers pierced the ring of barricades and forts at the bottom of the Butte and by noon had raised their tricolour on the telegraph station at the top. Forty-two guardsmen and several women captured in the fighting were taken to the house where the two generals had been shot, and executed. Louise Michel was captured, thrown into the trench and left for dead; she was still alive and escaped before giving herself up in return for the freedom of her mother.

The following day, fighting in the streets fragmented into localised battles. Communards burned down their headquarters at the Hôtel de Ville. Guardsmen shed their uniforms and many quit the city, leaving a final force to fight on under skies darkened by smoke from the incinerations, which now included the main law courts, the police prefecture the Palais de Justice, theatres and churches.

Wednesday 24 May. Summary executions continued, the army sometimes using machine guns to mow down prisoners. The head of the committee of public safety killed four prisoners, and was then captured and shot. The archbishop of Paris and five other hostages were executed in the courtyard of their prison. Guardsmen took forty-seven prisoners, including ten priests and twenty-seven policemen from the La Roquette jail, lined them up along a wall and shot them before bayoneting and beating the corpses with rifle butts.

Thursday 25 May. The Communard leader, Delescluze, wearing his outfit of the revolutionary days of 1848 – top hat, frock coat, black trousers and boots – donned his red parliamentary sash, climbed onto a barricade and was shot dead.

Friday 26 to Saturday 27 May. After six hours of heavy fighting, the army took the Place de la Bastille but was still subject to artillery bombardment from Commune strongholds in the Buttes-Chaumont and Père-Lachaise districts. After Foreign Legion troops captured the first, the battle focussed on Père-Lachaise. A savage evening battle ended with the last 150 guardsmen overwhelmed, put against a wall and shot.

‘There has been nothing but general butchery,’ the American minister to France, Elihu Washburne, wrote. ‘The rage of the soldiers and the people knows no bounds. No punishment is too great, or too speedy, for the guilty but there is no discrimination. Let a person utter a word of sympathy, or even let a man be pointed out to a crowd as a sympathiser and his life is in danger. A well-dressed respectable looking man was torn to a hundred pieces . . . for expressing sympathy for a man who was a prisoner and being beaten almost to death.’

End of the ‘war against Paris’

By Sunday 28 May, the ‘Bloody Week’ was over. Zola, who approved of the action by the Versailles government, described the city as ‘a vast cemetery . . . a lugubrious necropolis where the odours of the morgue lingered on the pavements’. The death toll among the insurgents has traditionally been put at 20–25,000, with some estimates going as high as 30,000. The army reported 877 killed, 6,454 wounded and 183 missing in the civil war as a whole. The official record showed 43,522 prisoners, 1,054 of them women and 615 under sixteen. Seventy-eight per cent of those arrested were workers, almost identical with the figure for 1848. In all, 22,727 captives were freed before trial on attenuating circumstances or humanitarian grounds. Nearly 16,000 were put before courts and 13,500 were found guilty with 95 sentenced to death and 251 to forced labour. Among other sentences, 4,316 were deported to French colonies and 4,616 went to prison, 40 per cent for less than a year.

Twenty-five Communard leaders were shot. Louise Michel asked for the death penalty, but was deported to New Caledonia where she worked as a schoolteacher. Courbet was sentenced to six months in prison, and later ordered to pay the cost of rebuilding the Vendôme column; he preferred exile in Switzerland and died there before the first payment was due. Seven thousand people went into exile, half of them to London.

The generally accepted Communard death toll of 20–30,000 was an essential element in the campaign for amnesties for those sentenced to prison or deportation and was then used as a graphic illustration of the ruthless and bloodthirsty nature of the right epitomised by Thiers and the generals. The notion of ‘the war against Paris’, the title of a book published in 1880, entered folklore. In fact, much of the city was not affected by the fighting. Half the population had abstained from voting for the Commune committee and felt no commitment to the insurrectionists. When a member of a parliamentary enquiry quoted a general as mentioning a figure of 17,000 for those killed in combat or afterwards, MacMahon said it seemed exaggerated and added that the general might have included wounded as well as dead. A paper delivered in 2011, by the historian Robert Tombs, argued that the number killed was in the range of 6–7,500, including some 1,400 Communards executed by the army. Still a large number, but much lower than the figure generally quoted. Tombs’s work, based on meticulous examination of the records, is convincing, but is unlikely to shake the central story of 1871, 20–30,000 deaths of Parisians at the hands of an army defending the middle and upper classes, making the Bloody Week of May central to the revolutionary tradition.

Lenin judged the Commune a living example of the dictatorship of the proletariat even if it had ‘stopped halfway’. Marx wrote that it would be ‘forever celebrated as the glorious harbinger of a new society’. Engels depicted it as a transition to a new order run by and for the workers. It certainly envisaged innovative left-wing measures, but did not have time to implement many. Extreme radicals were always in a minority. The main dynamic was the attempt to assert the special nature and position of Paris against a national government determined not to recognise that. In this respect, it fitted a pattern stretching back to 1789 and followed up in 1830 and 1848. Edmond de Goncourt judged that the repression ‘by killing the rebellious part of a population, postpones the next revolution . . . The old society has twenty years of peace before it.’ He was wrong in his timing; despite recurrent periods of crisis, the regime that followed would stretch for more than three times as long as he thought and then be renewed in much the same form for another fourteen years.