A twin-engined bomber that experienced severe handling problems, and a phenomenal accident rate in its early days, was the Martin B-26 Marauder. One of the most controversial Allied medium bombers of the Second World War, at least in the early stages of its career, the Glenn L. Martin 179 was entered in a US Army light and medium bomber competition in 1939. Its designer, Peyton M. Magruder, placed the emphasis on high speed, producing an aircraft with a torpedo-like fuselage, two massive radial engines, tricycle undercarriage and stubby wings. The advanced nature of the aircraft’s design proved so impressive that an immediate order was placed for 201 examples off the drawing board, without a prototype. The first B-26 flew on 25 November 1940, powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-2800-5 engines; by this time, orders for 1131 B-26A and B-26B bombers had been received, and training establishments had been set up at MacDill Field, Tampa, Florida and Barksdale Field, Louisiana.

The first unit to rearm with a mixture of B-26s and B-26As was the 22nd Bombardment Group (BG) at Langley Field in February 1941. Early in 1942 it moved to Australia, where it became part of the US Fifth Air Force, attacking enemy shipping, airfields and installations in New Guinea and New Britain. It carried out its first attack, a raid on Rabaul, on 5 April 1942. During the Battle of Midway in June, four B-26As of the 22nd and 38 th BG attacked units of the Japanese fleet with torpedoes.

Meanwhile, at the B-26 training bases in the United States, all was far from well. Many of the pilots reporting for training on the B-26 had no previous twin-engined experience, and soon the accident rate had reached such a level that the Marauder’s future was placed seriously in jeopardy. Most of the accidents occurred during the take-off or landing phase; the increases in weight that had been gradually introduced on the B-26 production line had made the wing loading of the Marauder progressively higher. This resulted in higher stalling and landing speeds, which novice twin-engine pilots found difficult to master. Before long, the B-26 had earned itself an unenviable reputation as a ‘widowmaker’ and a ‘flying coffin’. Early in 1942, the accident level at MacDill had become so serious that the expression ‘one a day into Tampa Bay’ became commonplace.

Such was the concern about the Marauder’s accident rate in senior USAAF circles that there was discussion about ceasing production of the type and withdrawing it from service. The US Senate’s Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program (better known as the Truman Committee, after its chairman, Senator Harry S. Truman), which had been charged with ferreting out corruption, waste and mismanagement in the military procurement effort, also began looking into the Marauder’s safety record. By July 1942, the committee had heard so many Marauder horror stories that they recommended production be stopped. However, combat crews in the South Pacific, who were more experienced, were not reporting any particular problems with the aircraft, and they campaigned for the Marauder. They exerted pressure, and the USAAF decided to continue production of the Marauder.

The situation at the training establishments, however, continued to worsen, with accidents becoming even more frequent. By September 1942, the B-26 had acquired such a bad reputation that even civilian crews under contract to ferry the type to its various destinations were refusing to fly the type, often losing their jobs as a consequence. A full investigation into the Marauder’s disastrous loss rate was initiated by the USAAF’s Air Safety Board, and in October the Truman Committee recommended that production should cease. By no means convinced that this decision was the right one, General H.H. Arnold, Commanding General of the USAAF, stepped in at this juncture. He turned the investigation over to Brigadier General James H. Doolittle, who in April 1942 had led sixteen B-25 Mitchell bombers, flown off the carrier USS Hornet, in a daring raid on Japan.

Doolittle was exactly the right man for the task. One of the leading pioneers of American aviation, he had learned to fly with the US Army in 1918. In the years after the First World War his flying career had been marked by a number of notable ‘firsts’. He had become the first man to span the American continent with a flight from Florida to California; the first American to pilot an aircraft solely by instruments from take-off to landing; the first American to fly an outside loop; and in 1925 he had won the coveted Schneider Trophy for the United States. He had also been a test pilot for the Army Air Corps, had demonstrated American fighter designs overseas, and – of vital importance to his new assignment – he had obtained the degree of a Doctor of Science in aeronautical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. During 1941, General Arnold, an old friend, used him as a kind of troubleshooter to deal with the hundreds of problems that arose as the US aircraft industry strove to gear up its resources to meet the growing demand for modern aircraft by the armed forces. Doolittle now had a personal interest in the Marauder, as he had recently been given command of the B-26-equipped 4th Medium Bombardment Wing, which was scheduled to take part in the invasion of North Africa.

Doolittle’s conclusion, supported by the Air Safety Board, was that there was nothing intrinsically wrong with the B-26, and there was no reason why it should be discontinued. They traced the problem to the inexperience of both aircrews and ground crews, and also to the overloading of the aircraft beyond the weight at which it could be safely flown on one engine only. Almost immediately after the Marauder had entered service, it had been found necessary to add more and more equipment, armament, fuel and armour, driving the gross weight steadily upwards. By early 1942, the B-26 had risen in normal gross weight from its original 26,625 lb to 31,527 lb with no increase in power. It had been found that many of the accidents had been caused by engine failures, which were in turn caused by a combination of poor maintenance by relatively inexperienced mechanics and a change from 100 octane fuel to 100 octane aromatic fuel, which damaged the diaphragm of the carburettors. Many of the B-26 instructors were almost as inexperienced as the pilots they were trying to train, and did not know themselves how to handle the B-26 in asymmetric configuration – in other words, on one engine only. Consequently, they were in no position to pass on the necessary technique to their pupils.

Doolittle sent his technical adviser, Captain Vincent W. “Squeak” Burnett, to make a tour of OTU (Operational Training Units) bases to demonstrate how the B-26 could be flown safely. These demonstrations included single-engine operations, slow-flying characteristics, and recoveries from unusual flight attitudes. Captain Burnett made numerous low-altitude flights with one engine out, even turning into a dead engine (which aircrews were warned never to do), proving that the Marauder could be safely flown if you knew what you were doing. Martin also sent engineers out into the field to show crews how to avoid problems caused by overloading, by paying proper attention to the aircraft’s centre of gravity.

The efforts of the Army and the Martin Company to improve training soon began to pay dividends. Within a few weeks B-26 accidents at the training establishments had been reduced to about the same level as that experienced by other combat types. Despite this, inevitable rumours persisted that the B-26 was a death trap, and new crews were extremely wary of it. It took the Marauder’s prowess in action to prove that it was, in fact, a superb fighting machine. It excelled itself in New Guinea, making fast, low-level attacks on Japanese airfields and installations that left the enemy dazed and bewildered.

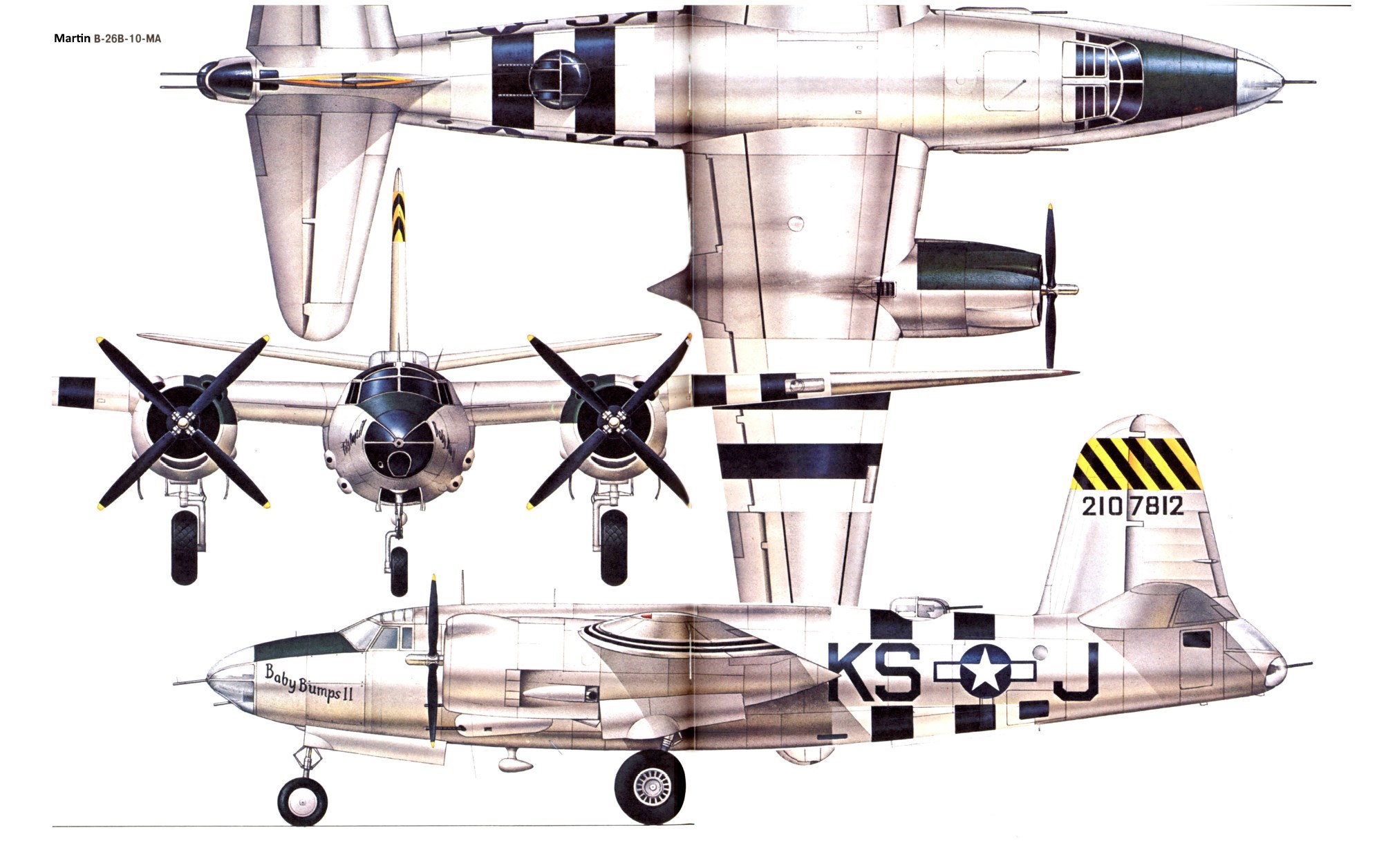

The original operational Marauder group, the 22nd BG, used B-26s exclusively until October 1943, when some B-25s were added. In February 1944 it became a heavy bombardment group, equipped with B-24s. The next variant, the B-26B, had uprated engines and increased armament. Of the 1883 built, all but the first 641 aircraft featured a new extended-span wing and taller tail fin.

The B-26B made its debut in the European Theatre with the 322nd BG in March 1943. After some disastrous low-level daylight attacks, all B-26 units in the European Theatre were reassigned to the medium-level bombing role. They fulfilled this role magnificently until the end of the war in both north-west Europe and Italy. The B-26C, of which 1210 were built, was essentially similar to the later B-26B models. These were succeeded by the B-26F (300 built), in which the angle of incidence (i.e. the angle at which the wing is married to the fuselage) was increased in order to improve take-off performance. The final model was the B-26G, which differed from the F model in only minor detail; 950 were built.

The B-26 saw service in the Aleutians in 1942, and in the Western Desert, where it served with the RAF Middle East Command as the Marauder Mk I (B-26A), Marauder Mk IA (B-26B), Marauder Mk II (B-26F) and Marauder Mk III (B-26G). Only two RAF squadrons, Nos 14 and 39, used the Marauder. The total number of Marauders delivered to the RAF included 52 Marauder Mk Is and Mk IAs, 250 Marauder Mk IIs and 150 Marauder Mk IIIs. The Marauder was also used extensively by the Free French Air Force and the South African Air Force. Many Marauders were completed or converted as AT-23 or TB-26 trainers for the USAAF and JM-1s for the US Navy, some being used as target tugs. Production totalled 5175 aircraft.