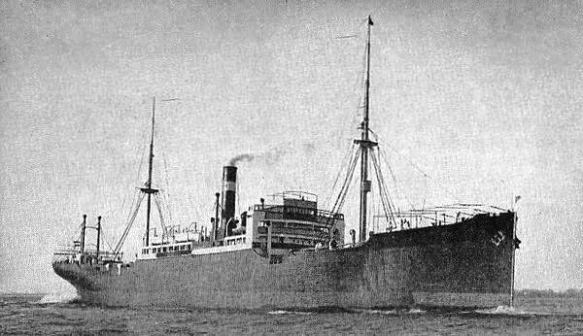

The raider Wolf(II) sailed on 30 November 1916. The raider was formerly the Hansa Line’s Wachtenfels (5,809 tons), now armed with seven 15-cm guns, three smaller guns for arming auxiliaries, four torpedo tubes, 465 mines, and a Friedrichshafen seaplane, dubbed Wölfchen. Her commander, Korvettenkapitan Karl-August Nerger, had by far the longest cruise—close to fifteen months—of any raider during the war, for the Wolf did not return to German waters until the latter part of February 1918. The Admiralstab ordered Nerger to mine the approaches to major ports in South Africa and British India and to continue the war against commerce only after he had expended his mines. His major objective was then to be the grain trade between Australia and Europe.

The Wolf was escorted through the North Sea by U-boats, passed through an ice field in the Denmark Strait, and then made the long journey to South African waters without attacking any ships. She laid her first minefield off the Cape on the night of 16 January. Nerger laid minefields off Capetown, Cape Agulhas, Colombo, and Bombay during the months of January and February. On 28 February he captured the British steamer Turritella (5,528 tons), which he commissioned as the auxiliary cruiser Iltis, and, after arming her and transferring 25 mines, ordered her to operate in the Straits of Perim and mine the main channel between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. The captured Chinese crew agreed to work under the Germans.

British, French, and Japanese warships on the Cape, East Indies, and China stations had been placed on guard against raiders in January, but this had been based on news the Möwe was out. There was no definite intelligence of the Wolf until 5 March. In February, March, and April of 1917 there were approximately 31 cruisers (including 10 Japanese and 3 French), 14 destroyers (British, Australian, and Japanese), and 9 sloops searching for the raider. By the end of March, there was even the old battleship Exmouth working the transport route between Colombo and Bombay, and in April the light cruisers Gloucester and Brisbane were detached from the Adriatic and Australia, and a seaplane carrier, the Raven II, arrived at Colombo. The significant Japanese contribution has largely been forgotten, although Newbolt admitted in the official history that the Japanese did rather more than was asked of them and really became the predominant partner in the Indian Ocean. There was eventually a Japanese vice admiral at Singapore with four cruisers and four destroyers, and another Japanese rear admiral with two cruisers protected commerce on the east coast of Australia. Two Japanese cruisers patrolled in the region of Mauritius and then escorted traffic between Mauritius and the Cape, and another detached squadron of two Japanese cruisers escorted traffic between Australia and Colombo.

The Iltis was not particularly successful. Shortly after laying her minefield, which subsequently damaged but did not sink two ships, she was challenged by the sloop Odin in the Gulf of Aden on 4 March and scuttled herself to avoid capture. The Admiralty responded to the news by first halting all transports in the Indian Ocean and then escorting one or two transports with cruisers while other patrols searched fruitlessly for the raider. The Wolf continued to coal from prizes, and after six months at sea overhauled her engines and boilers at remote Sunday Island in the Kermadecs northeast of New Zealand. Nerger then proceeded to lay mines off the northwest corner of New Zealand and then near the Cook Strait and in the Bass Strait. The Wolf’s final minefield was laid off the Anamba Islands near Singapore. The Admiralty, having had no news of the Wolf for some time, had canceled the Indian Ocean escorts on 2 June, and when the raider reentered the Indian Ocean in September, shipping was unprotected.

Nerger, thanks to coaling from prizes, was able to prolong his voyage beyond original expectations. He was always far ahead of Admiralty intelligence in the vast oceans. For example, the report of the Wolf’s visit to the Maldive Islands in September did not become known to the Admiralty until December. They promptly resumed escorts of transports in the Indian Ocean. By this time Nerger was far away in the Atlantic, on his way home in company with the captured Spanish steamer Igotz Mendi (4,468 tons), which had been serving as a collier since her capture on 10 November. The Wolf, by now leaking badly, finally reached German waters on 17 February 1918, although the Igotz Menai ran aground in fog off Skagen and was interned by the Danes. The Wolf’s mines had sunk a total of 13 steamers (11 British) representing 75,888 tons. Three ships had been damaged by mines but brought safely into port. The Wolf also captured or sank another 7 steamers (5 British) and 7 sailing ships (one British), representing 38,391 tons for a combined total of 114,279 tons.118 This is of course impressive, but it represented a cruise of almost 15 months and would only average out to about 7,700 tons of shipping destroyed per month. It appears minuscule compared to what the U-boats were accomplishing.