Dornier Do.19

The die was cast and the wheels had been set irrevocably in motion for the re-formation of the German Air Force. Henceforward military and civil aviation in the Reich moved as one, Lufthansa being the instrument for training air crew, developing aids and proving new aircraft. Göring with his various offices, and fighting the Communists, was far to busy to concern himself with aviation. The task therefore devolved on Milch.

Milch’s first step was to create the fabric of an Air Ministry organisation out of the old commissariat with additional departments removed from the Transport Ministry. A central administration department was created with five offices and inspectorates as follows:

1 An office run by an Army Oberst, but later directly under Milch. In this unit the Navy and Army, previously separate, were brought together and gradually became an air operations staff. In the latter part of 1933 Oberst Wever was appointed chief, and in 1935 he became the first Chief of Air Staff.

2 A technical and production office under Oberst Wimmer.

3 Civil aviation and meteorology under Ministerialdirigent Fisch, a department taken over from the Ministry of Transport.

4 Administration, finance, food and clothing including a works department responsible for airfield construction under Kesselring.

5 Personnel was at first headed by a civilian but later by a military commander, Stumpff.

The ‘empire’ which Milch inherited seemed unimpressive on the surface but the years of secret work had not been wasted. A hard core of army and navy officers with flying experience was immediately available within the Defence Ministry. A large pool of enthusiastic young men learned the elements of aviation in the gliding clubs and the aircraft industry was still healthily in being although on a small scale.

That 20,000 men were included in the new Air Force from its inauguration in 1935 was the result of the Russian training centre and the gliding and sports flying movements. The National Sozialistische Flieger Korps (National Socialist Flying Corps or N.S.F.K.) run by Oberst Bruno Lörzer showed little result, but this organisation tok in large numbers of the gliding-school members. The pick of these were sent to the Verkehrsflieger Schule, the German airline pilots’ school which before Hitler’s accession to. power had bases at Brunswick, Warnemünde, Schieissheim and List. The school also continued the work of the Lipezk centre, having special courses for Reichswehr officers temporarily ‘discharged’ from military service.

Small batches of the civilian trainees at the Verkehrsflieger Schule were sent on short military training courses held at Schleissheim. There they attended lectures on basic military subjects and were given twenty-five hours flying on Albatross and Heinkel biplanes which included combat aerobatics and some air-to-ground firing practice. One of the pupils who graduated from the gliding schools to the airline pilots’ school and thence to Schleissheim was a young man named Adolf Galland, later to become known as the Generaleutnant, Inspector of Luftwaffe Fighters.

In May 1933 about seventy Verkehrsflieger Schule pupils were sent to Italy for fighter training but the five months spent on this were almost useless and the experiment was not repeated.

Hitler, during 1933 and 1934, was anxious to consolidate his position and allay any foreign fears on German rearmament. Thus work had to be continued in the utmost secrecy.

Milch, with a free hand, saw in Lufthansa the instrument on which to base a planned expansion without arousing undue outside suspicion. The so-called Lufthansa training schools, two land and two sea, which were financed with military money, were rapidly extended, new airfields were built, and orders placed with the aircraft industry. Air force training continued with the airline and from 1935 Lufthansa crews were on the military reserve. The second pilot’s seats of inland Junkers 52 transports were used to give advanced training to pilots from the elementary flying schools.

Above all Milch wanted a cautious and long-term policy to build up a strategic air force over a period of from eight to ten years. By this time there would be essential continuity of service and a strong cadre of qualified officers to take over senior posts. Some of the Air Ministry staff backed Milch to the full, but they found it impossible to resist Göring, who demanded that a five-year programme be accomplished in twelve months or less, and who roared with laughter at the suggestion that the first two to three years should be devoted solely to training the thousands of air and ground crews.

Göring had tasted the fruits of power. Although with his many appointments he managed to confer with Milch only four times a year he nevertheless sensed that in the new Air Force he would have a weapon of unlimited power which could add further to his laurels.

Any suggestions of steady expansion were ignored. Göring’s demands for immediate results were backed up by Hitler himself, who, while largely ignorant about air matters, believed Göring’s promises for the future Luftwaffe.

The German aircraft industry in 1933 had a labour force of only about 3,500 workers and its monthly average of production of all types of planes was thirty-one. The foresight of the planners at the Defence Ministry, at Lufthansa, and in the firms themselves, however, assured that the design teams were thoroughly up to date. They were able in a remarkably short time to produce sizable batches of trainers, transports, some biplane fighters and the prototypes of modern bombers such as the Heinkel 111 and Dornier 17. The aircraft that were to fight the Battle of Britain were, in fact, in the advanced design stage in 1933—the year Hitler came to power.

After toling-up and expansion in 1933, the industry was ready on January 1st, 1934, to receive Milch’s first full production programme for 4,021 aircraft covering the years 1934–5. This was intended to provide the basis for building up six bomber, six fighter and six reconnaissance Geschwader (wings) to act as operational instruction units for the increasing numbers of air and ground crews.

No less than twenty-five types of aircraft were included in this first programme. Despite this, production expanded at such a rate that from the monthly average of thirty-one in 1933 the figures increased to 164 a month and 265 a month in 1934 and 1935 respectively. No combat types were produced in 1933, but 840 came out of the shops in the following year, and 1,923 in 1935.

For these spectacular results the credit must certainly go to Milch, who not only expanded the factories then in existence with the aid of State loans but encouraged industrial undertakings to form aircraft and component divisions. Foremost among these were Blöhm and Voss the shipbuilders, Henschel the locomotive makers, and Gotha who built rolling stock.

Milch planned to allocate by far the largest number of aircraft, 2,168, to training and a further 1,085 to operational units which would have training duties. A further 115 machines were to go to Lufthansa.

The essence of the interim air force programme was to treat modern bombers as the first line and fighters as the second to have some counter to the growing French Air Force. Milch envisaged fighters assuming priority over bombers about 1937, but by that time his star had waned and those who took over never put the scheme into effect. This had serious consequences in the Battle of Britain.

Things were going so well and output was rising so fast that in January 1935 Milch was able to put into operation a larger and more comprehensive production plan based on the same types of aircraft. This was to raise annual output from 3,183 in 1935 to 5,112 in 1936.

These promising forecasts combined with Hitler’s growing security of position and the milk-and-water attitude of most European governments led, in 1935, to the unveiling to the world of the new Air Force.

On February 26th, 1935, Hitler officially created the German Luftwaffe with Göring as commander-in-chief. General Milch was Secretary of State for Air, and became effectively controller of the restyled Air Force. General Wever, the brilliant officer who had risen from an infantry regiment to head the command division of the Air Ministry, was made the first Chief of Air Staff. Some 20,000 officers and men and 1,888 aircraft were incorporated into the new service—a formidable beginning.

An unsuspecting and lethargic world was informed by Berlin on March 1st, 1935, that the Luftwaffe was a force in being. The work of von Seeckt and the ‘secret Air Force’ had achieved fruition.

The year 1935 was a gala one for the new Air Force. The units secreted in the flying clubs and in various military and para-military organisations were officially incorporated into the Luftwaffe. One of these ‘handovers’ was particularly ostentatious when, on March 28th, 1935, Hitler, accompanied by Göring and Milch, ‘accepted’ the new Richthofen squadron on the old army parade grounds at Berlin-Döberitz. The unit, equipped with He 51 biplanes, was formerly known as a squadron of the S.A. (Storm Troops).

In the same year an air staff college was opened, and anti-aircraft or Flak arm was subordinated to the Luftwaffe, the signals service was developed and the basic regional layout of the Air Force was inaugurated. Germany was divided into four main groups (Gruppenkommandos) with centres controlling flying units at Berlin, Königsberg, Brunswick and Munich. The administration supply and training operations devolved on ten air districts or Luftgaue.

Milch was intent upon training more and yet more air crew. He limited production to trainers and interim combat types such as the He 51 fighter and the Ju 52 transport converted into a bomber, while awaiting assessment of a range of modern prototypes under development in the factories.

The expansion, however, began to get out of hand when Hitler and the General Staff called for the largest striking force in the minimum time. Strategic planning was non-existent. Operations were evolved on the basis of new equipment available until finally aircraft dictated tactics.

The colossal building of the German Air Ministry which rose in the Leipzigerstrasse, Berlin, was to be one of the causes of German defeat. New staffs and sections which appeared daily were accompanied by new arguments and petty jealousies between department heads. Over all this ruled Göring, the First World War pour le Mérite fighter pilot who had no concept whatsoever of strategic air warfare or of up-to-date technical requirements. The ship was under sail but it lacked chart, course and helmsman.

There was one man whose foresight and ability to plan and co-ordinate could have changed the face and fortunes of the Luftwaffe. Major-General Wever was a pilot with an organising brain and an understanding of technology applied to air warfare. As the first Chief of Staff he laid tong-term plans which included the use of heavy four-engined bombers in large numbers. His plans were destined never to mature, for on June 3rd, 1936, he was killed while flying a Heinkel Blitz aircraft which crashed near Dresden.

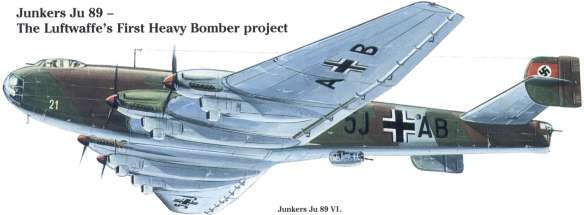

Wever had been closely associated with an official specification issued in 1935 for a four-engined bomber capable of carrying a sizeable weight of bombs to the north of Scotland and to the Urals from German bases. Prototypes were ordered from Dornier and Junkers. Both these were available for flights trials at the end of 1936. The Dornier 19, with four 650 h.p. Bramo 322 radial engines, had a speed of 199 m.p.h. and a range of 990 miles. Its Junkers counterpart, the Ju 89, had four 960 h.p. Daimler Benz DB600 engines, a top speed of 242 m.p.h. and a range of 990 miles at 200 m.p.h.

The machines required development modification, more tankage and higher-powered engines, but basically one or both could have formed the backbone of the world’s first strategic bomber fleet—and in time for the air war over Britain in 1940. Britain did not issue specifications for four-engined heavy bombers until 1936. At that time the Do 19 and the Ju 89 were already well advanced in the erecting shops, giving Germany a clear lead in Europe.

Wever, however, was dead and with him died Germany’s heavy bomber fleet. Kesselring succeeded to the post of Chief of Staff and proceeded with Göring and others to examine bombers then under development. It was decided to delete the heavy bomber from the programme and to emphasize the fast medium bombers and Stukas. Kesselring early in 1937 signed the cancellation order for the Do 19 and the Ju 89.

Colonel Wimmer, head of the technical branch, and other Wever supporters protested that at least a few prototypes should be completed and a full evaluation made. Göring remained adamant and when told by Kesselring that he had the choice between three twin-engined or two four-engined aircraft for the same money and production space remarked: ‘The Führer will ask not how big the bombers are, but how many there are.’

Even Milch, who had approved the original specification for the big bomber, sided with Göring and produced statistics to show that factory facilities and raw materials were lacking to build it.