The Treaty of Versailles, signed in June 1919, was intended to end German military aviation for ever. The Air Force was disbanded and to the victorious Allies were surrendered over 1,500 aircraft and 27,000 aircraft engines. Peace, like the Charleston, was in the air and in England Geddes of the anti-waste campaign was wielding his axe, reducing the Royal Air Force to a shadow of its former self.

In Germany, however, there was still a Defence Ministry. Here a man of considerable foresight understood the future of air power and determined to see the Air Force reborn. General von Seeckt, Chief of the Army Command, was an infantry soldier by profession, but he could see that one day air power would be of supreme importance in war.

As early as 1921 he began to secrete various promising men in offices of the Reichswehr Ministry in the Bendlerstrasse, Berlin. Their titles were innocuous and to the outside world they were small cogs in the treaty army of 100,000. Three of these officers were destined for high office and their names—Kesselring, Stumpff and Sperrle—were to become unpleasantly familiar in English homes twenty years later as Luftflotten commanders in the Battle of Britain.

Outwardly there was little for the ‘secret Air Force’ to do but watch technical advances in aviation abroad, produce staff papers and wait. The majority of the former Air Force drifted away to other jobs or stod in the unemployment queue. A much decorated young captain named Hermann Göring went as demonstrator and charter pilot to neutral Sweden.

The Defence Ministry, however, was far from wasting its time. One of its first moves to get round the treaty limitations was to send envoys in December 1921 to Russia to discuss aircraft manufacture and military aviation training for German recruits.

In December 1923 a secret agreement was signed covering military co-operation and the establishment of a flying school at Lipezk, about 200 miles south-east of Moscow. Buildings and land were provided by the Russians, but all equipment, aircraft, practice munitions and supplies were brought in secretly from Germany.

Training of the first entry began in 1924, the specially selected individuals being temporarily ‘retired’ from the armed forces and ‘re-enlisted’ on their return. Many have tended in post-war years to denigrate the part played by the Lipezk school, but the fact remains that several hundred crews, mechanics and other specialists, were trained in the nine years of its existence. The records show that the majority of officers who later held high rank in the Luftwaffe were Lipezk graduates.

In addition, the embryo air section at the defence headquarters in Berlin was able to carry out much aircraft and equipment development in Russia with the secret co-operation of the German aircraft industry. It is ironic that the Soviet Union should have provided the original facilities for the rebirth of the German Air Force—an Air Force which in 1941 was to all but destroy the Red air fleets.

Parallel to the Lipezk training, a future generation of pilots was being built up through the Deutscher Luftsportverband. Youths flocked to join this promising organisation which ran large-scale courses in glider instruction under Captain Kurt Student, head of the Reichswehr air technical branch. Later he became prominent as a general in command of parachute troops. From small beginnings in 1920 the Luftsportverband grew in nine years to a membership of 50,000.

German aircraft manufacture, contrary to popular belief, never ceased after World War I. On the morning of November nth, 1918, while the armistice delegates were meeting in the train at Compiègne, Professor Junkers, head of the firm which bore his name, his chief designer Ing. O. Reuter, and a group of engineers, forgathered to survey the future. Junkers informed them that they were to stop all military work and concentrate on the design for a civil transport. Thus, on June 25th, 1919, three days before the signing of the Versailles Treaty, the first post-war German aeroplane took to the air.

A complete breakaway from biplane types, the F-13, as it became known, was an all-metal, six-seater cabin monoplane. During the 1920s it was the most widely used transport aircraft in the world. Orders were at first few in a market glutted with war-surplus machines, but at the end of 1919 Junkers saved the firm closing by obtaining an order from America for six F-13s.

The Inter-Allied Aeronautical Commission then stepped in. All F-13s being built were confiscated, but after much discussion the Commission relented in February 1920 when it was decided that the F-13 was a genuine transport unsuited for military requirements. Its judgment, as usual, was not particularly sound. Within two years the Russians and Japanese were happily operating F-13s equipped with bomb-racks and machine-guns.

Just over a year later the Disarmament Commission thought again and F-13 production, in common with others, was stopped.

This did not deter Professor Junkers, who expected just such an edict. A former naval pilot, Gotthard Sachsenberg, Junkers’ travelling salesman, with his assistant, Erhard Milch, former air force officer, set about organising other facilities for the F-13. The problem of operating F-13s in the Reich was overcome by selling them to the Danzig Air Transport Company —whose manager also happened to be Erhard Milch.

Other German manufacturers had similar problems with the Disarmament Commission regulations but quickly found methods of circumventing them.

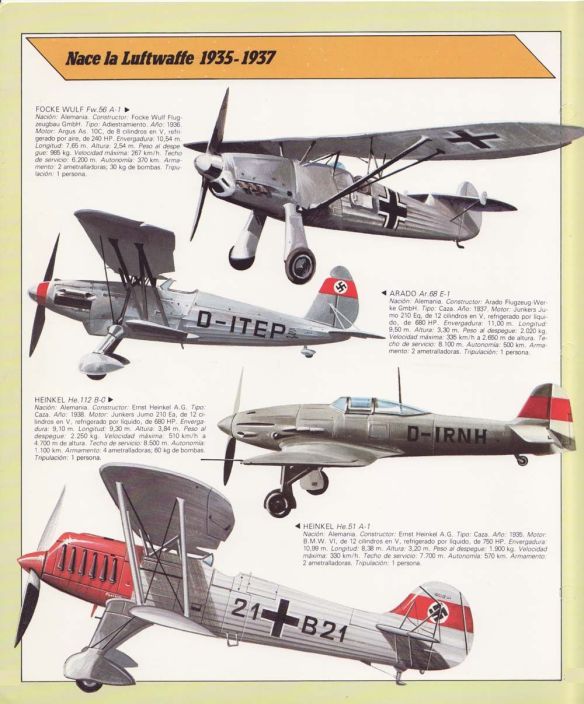

Claude Dornier produced a cabin flying-boat in 1919 and then promptly transferred development and production to Switzerland and Italy. Ernst Heinkel in 1922 began building an aircraft works at Warnemünde on the Baltic coast and also set up a factory in Sweden. In 1924 Heinrich Focke and Georg Wulf jointly founded the Focke-Wulf Company at Bremen. The following year Herr Messerschmitt bought out the Bavarian Aircraft Company and immersed himself in the design and production of high-speed sports aircraft.

Aircraft production went hand in hand with the development of Germany’s civil air services. Both were closely surveyed by the small band in the Defence Ministry.

On January 8th, 1919, the Reich Aviation Office licensed a new company, Deutsche Luftreederei, to operate air transport services. These began on February 5th with converted L.V.G. biplanes carrying mails between Berlin and Weimar.

Luftreederei grew at home and abroad where it co-operated with K.L.M., the Danish airline D.D.L. and the British company Daimler Hire. Its success and the subsidies granted by the state led to the mushroom growth of small airlines. By 1923 Luftreederei, with private capital, began the concentration of resources into two main companies, Deutscher Aero-Lloyd and Junkers Luftverkehr.

Professor Junkers found the operation of various airlines worthwhile for his factory. He sold more aircraft and the regular reports of trained pilots and sevice engineers allowed him to embody operating experience into designs.

Deutscher Aero-Lloyd and Junkers Luftverkehr made considerable progress but they lacked financial backing. The Government, seeing its subsidies being lost, insisted on amalgamation. Accordingly, on January 6th, 1926, Deutsche Lufthansa came into being with 37½ per cent of its shares in Ministry hands.

Behind the formation of Lufthansa was the astute Erhard Milch (later to become Field Marshal) who was appointed chairman of the airline. He wasted no time. Within one year Lufthansa flew four million miles and possessed a fleet of 120 aircraft. Highlights of the year included night passenger services between Berlin and Königsberg, connecting with Deruluft (Deutsche-Russische Luftverkehr) flights to Moscow, the flight of three tri-motor G-24s from Berlin to Peking via Russia, and the dispatch of a Dornier Wal flying-boat to investigate the route to Brazil.

Of even greater significance was the effort put into night and blind flying aids. In this first year these included beacon-lit airways for night operations and the provision of thirteen aviation ground radio stations. Lufthansa, from these small beginnings, was to provide the background and orders for the development of the German aviation electronics industry. Its navigation techniques became standard for the Luftwaffe and its fostering of the Lorenz beam approach system for airports led directly to the ‘X’ and ‘Y’ bombing beams of 1940 and 1941 which citizens of Coventry and elsewhere have reason to remember.

To Milch such ideas would have appeared ludicrous in 1926. He was intent on making Lufthansa the leading European airline. In the period from 1926 to 1928 the foreign-route network was expanded and the Baltic and the Alps were covered.

In 1928, however, a financial crisis hit the budding airline. Government subsidies were reduced from between fifteen and sixteen million Reichsmarks to little over eight and many of the Lufthansa staff were dismissed. Milch lobbied Reichstag deputies to press his case for more funds. One deputy, the thick-set former commander of the famous Richthofen Circus, Hermann Göring, lent a sympathetic ear.

Göring, then one only twelve Nazi Party deputies in the Reichstag, successfully pursued the cause of Lufthansa. He also told Milch in private that when the Nazis came to power they would create a new German Air Force. Thus was born a friendship which was to have far-reaching effects on Germany’s military future in the air.

At the Defence Ministry von Seeckt was not idle during these years. He was anxious to gain as much experience as possible from civil aviation and accordingly in 1924 managed to get his nominee, Captain Brandenberg, appointed to the post of head of the Civil Aviation Department of the Ministry of Transport, thus ensuring co-operation on civil development and ultimately its direction by the Defence Ministry.

The Paris Air Agreement of 1926 provided a setback to von Seeckt’s planners, as it heavily restricted the number of army and navy men who were permitted to fly. To overcome this stumbling-block arrangements were made through Captain Brandenberg to train military pilots in special sections of the Lufthansa commercial flying schools.

While the work of the air section of the Defence Ministry went on with varying degrees of success, the Nazi Party was fighting its way—with its own particular methods—to the top. Milch maintained his contacts with Göring until in 1931 he met Hitler. In the following year Göring invited Milch to throw in his lot with the Nazis but he preferred to wait and watch. On January 28th, 1933, Göring called on Milch and told him that the Nazi Party was about to seize power and pressed him to join. Still Milch held back. Two days later, on the morning of January 30th, Hitler was summoned to meet President Hindenberg and within two hours was Chancellor of the Third Reich.

Göring, trusted friend of Hitler, found himself right-hand man in a dictatorship. His devotion in the lean years of the ’twenties was rewarded with no less than four posts—one of which was Special High Commissioner for Aviation.

On his accession to power Hitler personally intervened in an attempt to persuade Milch to accept office. The latter’s wish to remain head of Lufthansa was met by his being appointed Göring’s deputy as Reichskommissar for Air while retaining the office of chairman of Lufthansa.

In April 1933 the Commissariat for Air was upgraded to the status of Air Ministry with Göring as Minister and Milch as Secretary of State. Milch was also secretly nominated by Hitler’s order as Göring’s successor in the case of the latter’s death.