Some months before the French invasion, the Russian Minister to Stuttgart, D. Alopeus, met a young German inventor Franz Leppich, who had earlier approached King Frederick of Württemberg with the grand idea of constructing a new kind of flying machines.

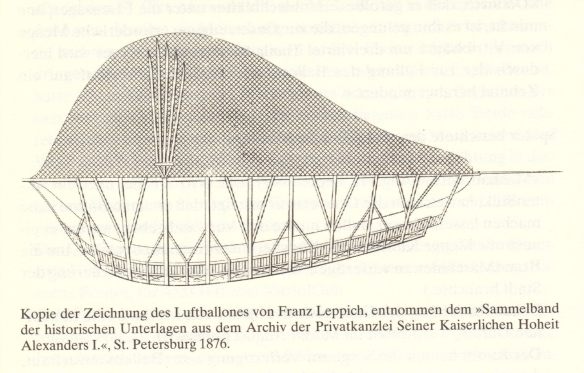

After Joseph and Étienne Montgolfier first flew them in 1783, hot air balloons had been used by the French military for reconnaissance. Leppich suggested improving their performance and turning them into fighting machines. The trouble with balloons, he explained, was their inability to fly against the wind, but by attaching wings they could be made to move in any direction. Although the idea seemed enticing, the King of Württemberg initially passed on it, especially after Napoleon rejected Leppich’s similar offer. But King Frederick later changed his mind and provided modest funding for Leppich’s experiments. The inventor was busy building his machine when, in early 1812, the Russian Minister approached him with a tempting offer to work in Russia. In his letter to Emperor Alexander, Alopeus described in detail a machine ‘shaped somewhat like a whale’, capable of lifting ‘40 men with 12,000 wounds of explosives’ to bombard enemy positions and sailing from Stuttgart to London in an incredible thirteen hours.

Leppich’s project appealed to Alexander, especially as war with Napoleon was looming, and any ideas that promised to give Russia an edge sounded attractive. On 26 April Alexander approved the project and Leppich’s workshop was set up at a village near Moscow, where Governor Rostopchin provided Leppich – now working under the alias ‘Schmidt’ – with all the production of artillery ammunition.

Maintaining secrecy over the project was of paramount impoance, but difficult to maintain. Suspicions were immediately aroused when guards were deployed around the estate. And they were further heightened when Rostopchin placed large orders for fabric, sulphurid acid, file dust and other assets, totalling a staggering 120,000 roubles. By July, some hundred labourers were working 17-hour shifts at the workshop. Leppich assured Rostopchin that the money was well spent and the flying machine would be completed by 15 August: by autumn entire squadrons would soar into the skies above Moscow!

On 15 July, Alexander personally visited the workshop and was shown various elements of the flying machine, including wings and a large gondola 15m long and 8m wide. The Emperor soon informed Kutuzov of the secret weapon and instructed him and Leppich to closely coordinate their actions in the future ‘air blitz’ against the French.

However, the deadline of 15 August passed without any results.

By now the invasion was under way and Napoleon was already at Smolensk. Rostopchin, beginning to suspect Leppich, demanded results. The scientist promised to deliver the machine by 27 August, but when nothing was forthcoming, Rostopchin wrote a letter to Alexander denouncing Leppich as a ‘crazy charlatan’. The machine was not completed by the time Borodino was fought, and the subsequent French advance threatened Leppich’s secret workshop: so it was loaded onto 130 wagons and moved to Nizhni Novgorod, while Leppich himself was recalled to St Petersburg.

Back in Moscow, Napoleon, already aware of rumours about a flying machine, ordered an investigation. Reports came back that some work had been done ‘by an Englishman who called himself Schmidt and claimed to be a German’. The purpose of this secret weapon, it was alleged, was to destroy Moscow before the French could seize it.

Meantime, Leppich continued his experiments at the famous Oranienbaum observatory. In November 1812 his first prototype balloon collapsed as it was wheeled out of the hanger. By September 1813 he finally built a flying machine that could ascend 12–3m above the ground – a far cry from his earlier promises of soaring squadrons in the skies above Russia.

In October 1813 General Alexei Arakcheyev launched an investigation into Leppich’s experiments and branded him ‘a complete charlatan, who knows nothing whatever of even the elementary rules of mechanics or the principles of levers’. Deprived of funding and in disgrace, Leppich left Russia in February 1814. By that time the Russian overnment had spent a staggering 250,000 roubles on Leppich’s project.