The bridges of late war U-boats had become crowded with radar and radar detection gear. Forced to operate submerged made the operation of such equipment more problematic, but also initially diminished its necessity somewhat.

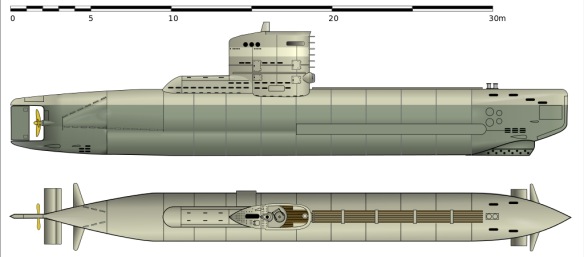

Rendering of a Type XXIII submarine.

At 1800hrs on the last day of January 1945, Oberleutnant zur See Hans Hass took U2324 from Kristiansand to its operational area off the Scottish coast in the Firth of Forth. Within seven days he had arrived in his patrol area, sighting a distant steamer but was unable to close the target enough to mount an attack. Finally his chance came on 18 February when he sighted and engaged a small coastal convoy in bad visibility fifteen miles east of Coquet Light on its small island off Amble. Hass fired his two torpedoes at a freighter, but missed due to a gyro-angling failure. Dejected, Hass headed back to Norway, berthing in Kristiansand on 25 February where the boat was put into the Bredalsholmen shipyard to prepare for its next patrol. Hass would not be commanding the small boat on its second sortie. Instead he was replaced by Kapitänleutnant Konstantin von Rappard who had begun his naval career as a watch officer aboard minesweepers in October 1939, entering the U-boat service in June two years later. Between November 1941 and July 1942 he had sailed as watch officer aboard the veteran Type IX U103 of Lorient’s 2nd U-Flotilla before being posted to command training boat U560. In August 1944 he became commander of the U-boat base at Kristiansand Süd where the Type XXIIIs were based, assuming command of U2324 in March 1945.

Hass’s patrol illustrated the major flaw in the Type XXIII as an offensive weapon. Though fast and manoeuvrable, the small U-boat possessed only a pair of torpedoes, fewer even than the Type II U-boat with which Germany had begun the war. The comparisons between the Type IID and Type XXIII are interesting. The Type IID carried five torpedoes, was capable of a range of 5,650 nautical miles surfaced, but only 56 submerged, with a top surfaced speed of 12.7 knots and 7.4 submerged. The Type XXIII carried two torpedoes and was capable of a range of 2,600 nautical miles surfaced, 194 submerged and top speeds of 9.7 knots surfaced and 12.5 submerged.

Undoubtedly the newer design was more mobile and effective as a submerged weapon of war, but despite its greater likelihood of survival compared to the Type II, the Type XXIII carried no more weaponry than the Seehund midget submarine (though the latter only possessed a maximum range of 300 miles at seven knots surfaced and sixty-three miles at three knots submerged).

By the time that Hass had returned from Scotland a second Type XXIII had also sailed for active service. Oberleutnant zur See Fridtjof Heckel took U2322 from Kristiansand on 6 February, again destined for the Firth of Forth. On 15 February near St Mary’s Head, Heckel attempted an attack against a British freighter estimated at 5,000 tons, though he missed and opted to retreat rather than waste his last torpedo. It was not until ten days later that he sighted convoy FS1739 south of Berwick and launched his last attack. U2322 had received radioed instructions from BdU that both itself and U309 – reckoned incorrectly to be nearby – were granted freedom to manoeuvre. Shortly thereafter FS1739 hove into view. The convoy was small and escorted by what appeared to be only a pair of small escorts. Heckel fired his last torpedo and hit the Danish ship SS Egholm, which had been requisitioned by the British Ministry of War Transport in 1940. Fatally holed, the 1,317-ton freighter sank in twenty-five metres of water with five men aboard killed. The Type XXIII had finally achieved victory in combat and Heckel headed for Stavanger, arriving on 3 March.

It was not only the two Type XXIIIs that had seen action during February in British waters. The beginning of the month saw twenty-six other boats at sea alongside U2324. Of these only nine were actually on station on 1 February 1945: U278 and U313 on the English east coast patrolling against potential British carrier groups; U245 off North Foreland; U1014 in the North Channel; U963 in the Irish Sea; U275, U1017, U1018, U480 and U244 in the English Channel. U275 was forced to break away from action during the early part of February with schnorchel damage. However, instead of heading for Norway Oberleutnant zur See Helmuth Wehrkamp took his damaged U-boat south to the encircled port of St Nazaire, where the besieged 30,000-strong garrison continued to hold out against the Allies. Enough material was still stored within the bomb-proof shelters to enable U275 to successfully perform emergency repairs of the troublesome schnorchel installation.

On 20 February U1004 reached its operational area at the western entrance to the English Channel. Oberleutnant zur See Rudolf Hinz had taken his boat from Bergen at the end of January on his second patrol of British waters. On 22 February southeast of Falmouth U1004 found the small fourteen-ship coastal convoy BTC76 sailing from Bristol to the Thames. That afternoon Hinz fired a single T5 Zaunkönig and two LUT torpedoes and managed to sink two ships. The first was the 1,313-ton British freighter SS Alexander Kennedy loaded with coal. A single crewman was lost with the master, John William Johnson; fifteen crewmen and two gunners were later rescued. For his bravery during the sinking Johnson was later awarded the Lloyds War Medal (established in 1940 and bestowed on 541 merchant seamen for gallantry during the war).

Nine minutes after SS Alexander Kennedy was hit, U1004 hit the single Canadian escort, corvette HMCS Trentonian starboard aft; she sank quickly with the loss of one officer and five ratings. The commander, Lieutenant Colin Glassco later recalled:

We had barely cleared the convoy when we were hit. The torpedo struck the ship at the starboard after depth charge thrower, blowing a large hole in the hull, and flooding the engine room. She settled very quickly and when the Engineer Officer and First Lieutenant said it was beyond repair, I gave the order to abandon ship. The men behaved with great courage and cheerfulness. Fortunately the men in charge of the depth charges had set them to safe, otherwise they would have gone off when the ship got down to the prescribed depth and the explosion would have killed most of us. The need for wearing life jackets was borne out by the fact that we lost no one by drowning despite the fact that more than fourteen of the crew could not swim. We were in the water for forty-five minutes waiting for the Fairmiles (motor launches) to pick us up, the men sang to pass the time and to keep spirits up. The crew’s biggest complaint was the wasted effort they had just put into giving the ship a new coat of paint. The water was thirty-three degrees, and the effect on one’s strength was very noticeable when climbing up the scramble net.

In all situations of this kind there is always a Court of Inquiry, and this was held at the Naval Base in Plymouth. The officers and crew were mustered outside the door where the Inquiry was to be held, and along came a warrant officer bearing a sword and placed it on the table. My heart sank as in my rather nervous state it looked as if the Court of Inquiry was to be dispensed with and they were going straight into a Court Martial. Happily it was all a mistake and the little warrant officer came back saying cheerfully, ‘Sorry sir, wrong room’.

To my relief, the President of the Court confirmed the correctness of our tactics, and that we had intercepted a torpedo aimed at one of the 10,000-ton Liberty ships. The first paragraph of Atlantic Convoy Instruction reads; ‘The safe and timely arrival of the convoy is the first duty of the escort’; so in this case we really carried out our duty, and in the process lost our ship.”

U1004 narrowly missed hitting a third ship; the explosion of the second LUT torpedo as it sank at the end of its run was clearly heard inside the German hull and causing Hinz to claim a third victim sunk.

In Berlin, BdU fought blind as they traced the presumed positions of their U-boats, optimism often overruling caution in the précis of action presented by Dönitz to Hitler:

The Führer is particularly pleased about the reports of the latest submarine successes. In this connection, C-in-C Navy reports that seven submarines have recently returned from operations in the areas around the British Isles. These ships had to operate in narrow sea lanes and in shallow waters near the coast. They all report that the enemy defences are not very effective. This proves therefore that the superiority of the enemy submarine defences has been overcome by the introduction of the schnorchel. The number of submarines in operation will be increased further in the near future. Since the beginning of February thirty-five submarines have left for operational areas, and twenty-three more will follow before the end of the month. The Führer asked … about the use of the new submarine types and was informed that two of Type XXIII are already operating along the east coast of the British Isles and that the first ship of Type XXI will be ready for operations along the American east coast by the end of February or the beginning of March.

One further boat, U907, was on weather-reporting duty near Iceland, a seemingly thankless task for any U-boat crew, but something that BdU not only valued, but also could interpret in a way that emphasised the supposedly favourable position that the new U-boat offensive had created:

One to two boats have been detailed continually in the North Atlantic during the past year, to make weather reports every day. These weather reports were and are included in the formation of the general weather conditions in Europe, and also in a review of the conditions at the front, of the defences of the Reich and all such operations in which a report on the enemy air forces is of such great importance. The weather boats were increased to three at the beginning of December, to ensure that enough reports were received daily as were necessary for us to start the West Offensive.

Although the boats, whose positions were well known to the enemy owing to their extensive use of wireless telegraphy, were attacked now and then at the beginning of the year, this has no longer been the case during the last three months: It shows that the enemy’s Atlantic air patrols have decreased over the open sea to enable them to cover the coastal waters to a width of about 400 miles, that is to say, their own outward and supply routes to Norway.

German U-boat casualties mounted almost immediately from the beginning of February 1945, as the boats operated in bad winter weather near the British Isles. The new Type VIIC/41 U1279 captained by Oberleutnant zur See Hans Falke had been at sea only four days when, on 3 February, it was detected by the British frigates HMSs Bayntun, Braithwaite and Loch Eck, which were sailing to their new billet at Scapa Flow, north-northwest of the Shetlands. The boat was sunk by depth charges with all hands.

The following day the Type VIIC/41 U1014 was located in the North Channel and sunk by HMSs Loch Scavaig, Loch Shin, Nyasaland and Papua. Oberleutnant zur See Wolfgang Glaser had only arrived in his operational area a few days previously at the end of January. HMS Loch Scavaig detected the boat lying on the bottom north of Portrush, and began depth charging as four other frigates of the 23rd Escort Group joined the attack, eventually destroying U1014 and its crew. Another VIIC/41 U989, which had survived a patrol in the English Channel during the August of 1944, was also sunk on 14 February east of the Shetlands, having been located by four frigates of the 10th Escort Group while bound from Horten to British waters. The captain, Kapitänleutnant Hardo Rodler von Roithberg and one crewman actually succeeded in escaping the submerged and sinking U-boat and were picked up by their British attackers, but both died shortly afterward, possibly due to internal injuries caused from escaping a U-boat from too great a depth. It was von Roithberg’s 27th birthday. His U-boat career had begun in September 1940 as second watch officer aboard U96 – the boat made famous by the book and film Das Boot.