Heinkel He.111P medium bomber of III/KG54 (Kampfgeschwader), Norway, April 1940.

Except for a small group of very experienced long-range reconnaissance pilots, the Luftwaffe entered the war with limited experience in operations over water and few of its pilots had any experience at all in anti-shipping operations. This had to some extent improved during the winter and spring of 1940, but due to inter-service rivalry the situation was far from ideal. In the plans for the reconstruction of the German Navy, several Küstenfliegergruppen (coastal aviation groups) were assigned to the Kriegsmarine for reconnaissance and bombing missions in addition to the Trägergruppen to be operating from the planned aircraft carriers. Göring, however, saw that the carriers might become prestige projects and decided that the Luftwaffe should be fully responsible for all aspects of flying off them. For good measure, he also added all other aspects of naval air operations such as mine laying, attacks on shipping and reconnaissance, claiming ‘… anything that flies, belongs to me!’ This meant that the ambitious plan for a naval air force was all but abandoned in favour of fighters and army support aircraft. Even worse, as the total responsibility also included communication, it meant that any information from the aircraft was delayed for several hours while it ascended the Luftwaffe chain of command and then back down through the naval command to the ships.

In September 1939, Generalleutnant Hans Ferdinand Geisler had been ordered to establish the X Fliegerdivision with one specific task: conduct anti-shipping warfare against the Allies. Oberstleutnant Martin Harlinghausen was assigned as his Chief of Staff and they settled at Blankensee near Lübeck. The first unit assigned to X Fliegerdivision was the Heinkel He111-equipped KG 26 ‘Löwen Geschwader’ under Oberst Robert Fuchs.

The He111 was a sturdy but relatively slow medium bomber, far better suited to the intended tactical support role than chasing naval targets. In spite of a respectable bomb load, level bombing of agile warships was rarely successful, except where the ships were trapped in harbours or confined waters. On the open sea, they could usually turn away in time to avoid the bombs.

A significant addition to the corps would come in the form of KG 30 ‘Adler Geschwader, equipped with Junker Ju88 aircraft, pressed into service in the early days of the war. This sleek, twin-engine bomber was significantly faster than the He111 and, as it had dive-brakes, the bombs could be delivered from low level through a steep dive; far more suitable against warships than level bombing. The first operational Ju88s were assigned to Geisler’s command in late September 1939. At the same time, his unit was upgraded to a full air corps and renamed X Fliegerkorps. By April 1940, all three Gruppen of KG 30 under Oberstleutnant Walter Löbel were fully operational with Ju88s. The Eagles of KG 30 and the Lions of KG 26 were to develop a close partnership in the months before the attack on Norway. KG 26 would primarily concentrate on merchant shipping while KG 30 would take on the Allied navies.

On 12 April, Luftflotte V was established in Norway under the command of General-oberst Milch, who was to be in charge of all aircraft in that country, including transport units. Göring soon decided that Milch was needed for the campaign on the Western Front, however, and replaced him in early May with General Stumpff.

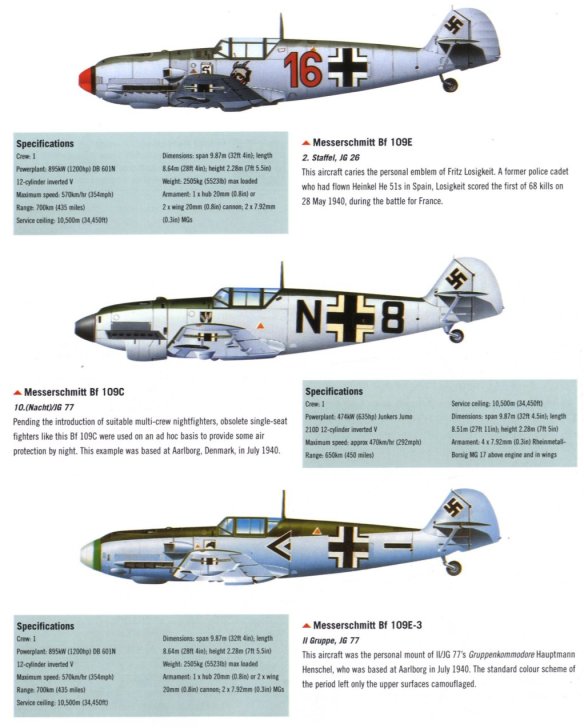

During early April, the He111-equipped KG 4 and Kampfgruppe KGr 100, as well as the Fw200 Condor-equipped 1./KG 40 and Stuka-equipped I/StG 1 were temporarily assigned to X Fliegerkorps. After the invasion, two groups from Lehrgeschwader LG 1 and II/KG54, flying a mix of He111s and Ju88s, were also added. This meant that the entire maritime and anti-shipping experience of the Luftwaffe was engaged in Norway. By 26 April, when the German air offensive was at its peak, five hundred aircraft were available to Luftflotte V for use in Norway. Apart from the single-seat Bfì.09 fighters of JG 77 at Kjevik-Kristiansand, virtually all Luftwaffe fighter missions over Norway in the spring of 1940 were flown by the half-dozen Ju88C heavy fighters of Z/KG 30 or the twin-engine, two-seater Messerschmitt Bf110s of I/ZG 76. Both units were based at Sola-Stavanger from 10/11 April until transferred to Værnes on 1 May and 20 May, respectively.

The aircraft flew from several airfields in northern Germany, Denmark and Norway, often using Fornebu-Oslo, Sola-Stavanger and Værnes-Trondheim as forward bases for multiple raids during one day. The majority of the aircraft returned to Aalborg in Denmark or a German airfield at night, though, to avoid congestion in Norway. When it was evident that the Norwegians would resist and that Allied forces would come to their assistance, the significance of the Norwegian airfields multiplied and their possession was eventually to be one of the vital factors of the German success.

The flying time from Fornebu or Sola to the Narvik area was substantial, and when it became clear that a major Allied expeditionary corps had landed there, Værnes-Trondheim was vital. No more than a grass-covered aerodrome, the thaw made it soggy and dangerous to use, and while repair work was carried out, the ice on nearby Lake Jonsvatnet was found more suitable. At times, up to fifty aircraft operated from the frozen lake. Following an attack on Namsos on 20 April, a number of the He111 of KGr 100 landed on the ice of Jonsvatnet, including the Gruppenkommandeur Hauptmann Artur von Casimir. During the next day, a rapid thaw made his aircraft sink into the softening ice. With no cranes or other heavy equipment available, the aircraft eventually vanished through the thinning ice in spite of the efforts of the ground crew to save it.

Work on Værnes started on 24 April and some two thousand Norwegian men from the district found it opportune, drawn by good money, cigarettes and alcohol, to report for work at the airfield, in spite of the fact that the aircraft to be flown from there would attack their countrymen in the still unoccupied parts of the country. On 21/22 April, the ice on Jonsvatnet became unusable, but by the 28th, an 800-metre wooden runway at Værnes was cleared for use and the next day, most of KG 26 was transferred from Sola, where it had been since 17 April.

It would be 20 June before the whole runway was completely rebuilt, but from early May Værnes was fully operational; at its peak, more than one hundred aircraft operated from there on a daily basis. Conditions were rather primitive though, and on 26 April, Admiral Boehm, Supreme Naval Commander in Norway, reported to Raeder after a visit to Trondheim that Værnes was ‘… small, sodden and miserable at this time of the year with low clouds hanging down from the surrounding mountains’.

From 3 May, X Fliegerkorps was significantly reduced. II and III/LG 1, as well as II/KG 54, were ordered to return to Germany for the attack in the West. Shortly after, parts of KG 26 and KG 30 were also pulled back. Most of the remaining aircraft were deployed at Værnes, from where they could reach Narvik more easily than from the airfields in the south, while remaining largely immune from anything but British carrier-borne attacks. By 10 May, the village of Hattfjelldal near Mosjøen, where there was a small airstrip that with some improvements could be used for refuelling, greatly increased the time the bombers could stay over the Narvik area.

In most of the summaries of the campaign in Norway, German air superiority is held to have been one of the most decisive factors affecting the outcome. There is little argument against this, but it is noteworthy that General Pellengahr, in his account of the events in Gudbrandsdal, holds that several other weapons were more important – among them, the heavy machine guns mounted on half-track motorcycles. In his summary of lessons from the campaign in Norway, General Auchinleck wrote:

The actual casualties caused to troops on the ground by low-flying attacks were few, but the morale effect of continuous machine-gunning from the air was considerable. Further, the enemy made repeated use of low-flying attacks with machine guns in replacement of artillery to cover the movement of his troops. Troops in forward positions subjected to this form of attack are forced to ground and, until they have learned by experience its comparative innocuousness are apt not to keep constant watch on the enemy. Thus the enemy were enabled on many occasions to carry out forward and outflanking movements with impunity. The second effect of low-flying attacks was the partial paralysis of headquarters and the constant interruption in the exercise of command. Thirdly, low-flying attacks against transport moving along narrow roads seriously interfered with supply, though this was never completely interrupted. Bombing was not effective against personnel deployed in the open, but this again interfered with the functioning of headquarters and the movement of supply.