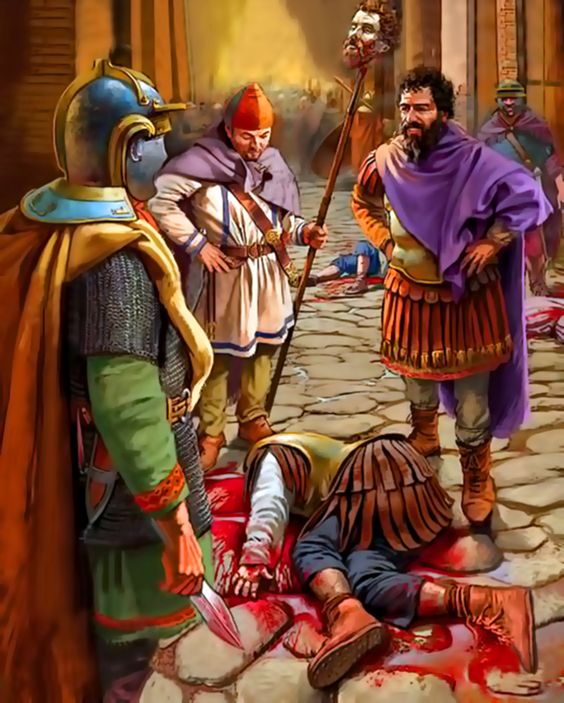

Septimius Severus and his men contemplating the corpse of his rival for the throne – after the first victory in the Battle of Lugdunum.

When Julianus was killed on 1 June 193, Septimius Severus was still some 80 kilometres from Rome. Nine days later his army flooded into the city in triumph having put the Senate and the Praetorians firmly in their place. A hundred-strong delegation of Senators had met him at Interamna (modern Terni), where he had them searched for concealed weapons, before receiving them, armed himself and accompanied by many armed men. The Praetorian Guard were also summoned (or tricked) to meet him ‘in their undergarments’outside the city, where they were ‘netted like fish in his circle of weapons’. They were stripped of their clothing and their employment, and forbidden to come within 100 Roman miles of Rome on pain of death; anyone directly involved in the murder of Pertinax was executed. A new Praetorian Guard was recruited from Septimius’ loyal Danubian legions, but he retained Julianus’ Praefectus Flavius Juvenalis, who had conveniently changed sides when offered the chance. Septimius did install a new co-commander of the Guard though, D. Veturius Macrinus, and more significantly a fellow-African and distant relative called C. Fulvius Plautianus became the new Prefect of the Vigiles and proceeded to seize Pescennius Niger’s adult children. These changes effectively put an end to Italians dominating the Praetorian Guard and were symptomatic of changes in the balance of power right across the Empire.

Dio Cassius witnessed Septimius’ entry into Rome at first hand:

The whole city had been decked out with garlands of flowers and laurel and adorned with richly coloured stuffs, and it was ablaze with torches and burning incense; the citizens wearing white robes and with radiant countenances, uttered many shouts of good omen; the soldiers, too, stood out conspicuous in their armour as they moved about like participants in some holiday pro cession; and finally we [Senators] were walking about in state.

Septimius posed as the avenger of Pertinax, whose name he included in his grandiose new title: Imperator Caesar Lucius Septimius Severus Pertinax Augustus. He provided the late ruler with magnificent obsequies in the Campus Martius: a pyre was constructed in the form of a three-storey tower adorned with ivory, gold and statues, on top of which was a gilded chariot. When the consuls set light to the pyre an eagle flew from it, symbolizing Pertinax’s deification.

Rome’s first 100 per cent African Emperor was

small of stature but powerful, though he eventually grew very weak from gout; mentally he was very keen and very vigorous. As for education, he was eager for more than he obtained, and for this rea son was a man of few words, though of many ideas. Towards friends not forgetful, to enemies most oppressive, he was careful of everything that he desired to accomplish, but careless of what was said about him.

His family were upwardly mobile wealthy denizens of Lepcis Magna, and his future had seemed particularly rosy when, early in his career, he consulted an astrologer who gave him a reading predicting ingentia, ‘great things’. He married a woman named Paccia Marciana, moved to Rome, became a Senator, and pursued a career of governorships and military commands under Marcus Aurelius and then Commodus, which culminated in his governorship of Pannonia Superior in 191. His success was partly due to Rome’s ‘African mafia’, especially Q. Aemilius Laetus, and although he was totally Romanized, he never lost his local accent: in all probability he pronounced his name Sheptimiush Sheverush.

His marriage to Paccia Marciana was childless, but his second marriage, to Julia Domna, produced two sons in quick succession: L. Septimius Bassianus (better known by his nickname Caracalla) in 188, and P. Septimius Geta the year after. He had, allegedly, chosen Julia Domna because it was written in the stars that she would marry a king, but she was a colourful character in her own right: the daughter of the high priest of the sun god Elagabal at Emesa (modern Homs) in Syria, striking to look at, adept at political machinations, a patroness of writers and philosophers, and well known for her scandalous love affairs:

[Septimius] kept his wife Julia even though she was notorious for her adulteries and even guilty of conspiracy.

There is a certain amount of irony in this. Septimius prided himself on his old-school Roman qualities of rigor, disciplina, severitas, etc., and felt that Rome’s population was not living up to the morals and values of their ancestors, but when he tried to enact the old lex Julia de adulteriis he created a backlog of literally thousands of indictments and he had to give up the process. Even the barbarians were disgusted, if we can believe Dio’s story of a conversation between a Caledonian woman and Julia Domna. The empress was teasing her about ‘free love’ in Britain, only to get the reply: ‘We fulfil the demands of nature in a much better way than do you Roman women; for we consort openly with the best men, whereas you let yourselves be debauched in secret by the vilest’.

Septimius did not stay in Rome for long. He still had the problem of the wannabe Emperor Pescennius Niger to deal with, but first he underwent an image change where rather than working a soldierly look he took on a heavily bearded style. Then he announced that he was embarking on a Parthian War, but headed for his real target – Byzantium, where Niger was based.

It was a classic East v West clash, with Pescennius Niger’s six legions from Egypt and Syria confronting Septimius’ sixteen mighty Danubian ones. The result was a foregone conclusion: Septimius’ battle group drove Niger’s men back towards the end of 193, scoring victories near Cyzicus and at Nicaea (modern Iznik), while his fleet brought troops to lay siege to Byzantium; the provinces of Asia and Bithynia fell into Septimius’ hands; Egypt recognized his authority; and in Spring 194, in a toughly contested battle at Issus (where Alexander the Great had famously defeated Darius III of Persia), his troops deployed testudo tactics and destroyed Niger’s army. Niger himself fled but was apprehended and beheaded. However, not even the display of his severed head could induce the defenders of Byzantium to capitulate: it took more than a year to bring them to submission, after which the city’s imposing walls were torn down.

Septimius tinkered with the provincial arrangements in the East: the province of Syria was now divided into two: Syria Coele (‘Hollow Syria’), which had quite a Hellenistic cultural flavour, and Syria Phoenice, ‘Phoenician Syria’, with a more strongly Semitic one. A vicious backlash also took place against the individuals and cities that had supported Niger. Such was the extent of the reprisals that a great many people fled to Parthia rather than face Septimius’ severity. This duly provided him with a pretext to invade Parthia, and in the first half of 195 he crossed the Euphrates into northern Mesopotamia. Dio says he did this out of a ‘desire for glory’, but it would do him no harm to bring his and Niger’s legions together against Rome’s traditional enemy, and the Parthians could not be allowed to support his rival and the fugitives with impunity. In fact, Septimius encountered little meaningful resistance. The kingdom of Osrhoene was made into the Roman province of Osrhoena, a chunk of Mesopotamia was organized as a Roman province of the same name with two legions stationed in it, and Septimius received three salutations as Imperator as well as taking the titles Arabicus andAdiabenicus.

The elimination of Niger and the annexation of new territory was really just a prelude to more important events at Rome and in the West. Septimius sought to link himself to the Antonine dynasty by (falsely) claiming that he was the son of Marcus Aurelius; Julia Domna received the title Mater Castrorum (‘Mother of the Camp’) like Marcus’ wife Faustina; and Septimius’ elder son Septimius Bassianus, aka Caracalla, was renamed Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. When the seven-year-old boy was given the title ‘Caesar’, Septimius’ dynastic plans were made crystal clear: Clodius Albinus had been granted this title to buy him off in the struggle with Niger, so replacing him with Caracalla was an open invitation to a fight.

Clodius Albinus had a certain amount of support in the Senate, and we hear that Septimius dispatched agents to assassinate him and put about allegations that he had been behind Pertinax’s murder. For his part, Albinus proclaimed himself Augustus (i.e., Emperor), but was declared a public enemy on 15 December. Popular unease about the situation manifested itself in a demonstration against civil war in the Circus Maximus, but events now had their own momentum. Albinus commanded the three legions of Britain, Legio VII Gemina in Spain, and forces from the Rhineland, but he was still outnumbered by an adversary who was better prepared. In February 197 the armies converged outside Lugdunum, where Septimius prevailed after some bloody fighting in which he was thrown from his horse and only escaped by throwing off his imperial cloak. The defeated Albinus committed suicide and Septimius rode his horse over his naked body before having it thrown into the Rhône, and his severed head was sent back to Rome.

Whereas Albinus had minted coins at Lyons professing his CLEMENTIA (‘clemency’) and AEQUITAS (‘fairness’), Septimius is said to have lauded the severity and cruelty of notorious Republican hard-men like Sulla and Marius, and deprecated the mildness of Pompey and Caesar. He argued that it was totally hypocritical for the Senators to criticize his ‘brother’ Commodus, when ‘only the other day one of your number [. . .] was publicly sporting with a prostitute who imitated a leopard’. The reprisals of ‘the Punic Sulla’ were savage: Albinus’ wife and children were killed, as were many of his supporters and their wives; twenty-nine Senators were put to death; and Commodus was deified. Herodian summarizes the situation very well:

But here is one man who overthrew three Emperors after they were already ruling, and got the upper hand over the Praetorians by a trick: he succeeded in killing Julianus, the man in the imperial palace; Niger, who had previously governed the people of the East and was saluted as Emperor by the Roman people; and Albinus, who had already been awarded the honour and authority of Caesar.

In an acknowledgement of where his true power-base was, Septimius curried favour with the people of Rome by staging extravagant and exotic shows in the arena, and with the army, notably by improving the legionaries’ basic pay from 1 200 to 2 000 sestertii and ending Augustus’ restrictions on their right to marry. Then it was time to head for the East once more. Parthia must be destroyed . . .

There was a slightly unsettled atmosphere on the Eastern frontier. The Parthian king, Vologaeses IV, had retaliated against the Roman incursion of 195 by attacking the frontier outpost of Nisibis, which had been taken during that campaign. Now, however, the Roman intentions were much more serious. The Emperor raised three new legions, I, II and III Parthica, all commanded by Equestrian prefects rather than Senatorial legates. Dio tells us that I and III were quartered in Mesopotamia but II Parthica was stationed in Italy, where it could both control Rome and function as a strategic reserve. By late summer 197 Septimius had established his headquarters at Nisibis. His invasion force sailed along the Euphrates before marching against Ctesiphon on the Tigris, which they took relatively easily. In a fate not uncommon in antiquity, the adult males were killed and the women and children enslaved, while the Parthian royal treasury was looted. Northern Mesopotamia became a Roman province once again, and on the centenary of Trajan’s accession, 28 January 198, Septimius took the title of Parthicus Maximus, named the nine-year-old Caracalla ‘Augustus’ (co-Emperor), and made his younger son Geta ‘Caesar’: essentially he now had an heir and a spare.