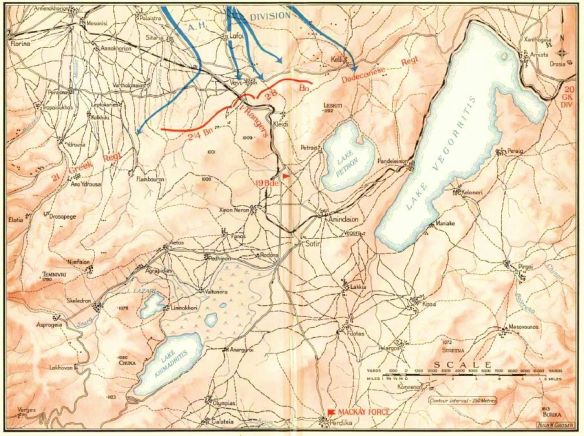

The dispositions of forces on 10 April. The blue arrows indicate German advances and the Allied lines are shown in red. Vevi and the Klidi Pass are upper centre, 19th Brigade HQ is in the centre and Mackay Force HQ is at Perdika, lower centre.

The hasty assembly of the defending force showed in myriad ways, one of the more comical being the arrest by Greek police of Lieutenant Colonel J. W. Mitchell, a Melbourne company director and now CO of 2/8th Battalion — the suspicious local constabulary thought the Australian colonel was a spy.

The defenders endured yet another snowfall during the night of 10 April, equipped only with greatcoats and blankets, sustained by hardtack and bully beef. In the cold and snow, the two sides fought further patrol actions, and the result for the Allies was not propitious. A German force of about 20 men infiltrated the centre-right of Mackay Force and, confusing their opponents by calling out in good English, captured 11 New Zealanders, six Rangers, and six men of the 2/8th Battalion. Fire-fights then broke out in front of the foremost element of the 2/8th Battalion, the 14 Platoon, entrenched on the forward slope of Point 997. In this confused action, two wounded SS men were taken prisoner, and from their insignia the Australians first learnt that the Leibstandarte was in the line against them. The more lightly wounded German was removed to Corps Headquarters near Elasson, where he was interrogated by Private Geoffery St Vincent Ballard, a German-speaking signaller with the 4 Special Wireless Section. Sitting on the tailgate of a truck, Ballard struck up a conversation with ‘Kurt’, established he was from Berlin, and gathered from him some ‘low-level information’ about the composition and role of the Leibstandarte.

The eleventh of April opened with a blizzard, and the Allied troops were united in their misery. The New Zealand machine-gunners had spent the night in sodden gunpits, their boots waterlogged. In the morning, they even found several guns frozen and unable to fire. Conditions on the higher ground occupied by the Australian infantry were more difficult again: the 2/8th Battalion, at least, finally found a use for their cumbersome and despised anti-gas capes, which helped to keep the men dry. Regardless of this modest protection, men began to drop out with frostbite.

At six o’clock that morning, Dietrich issued his divisional orders, forming a kampfgruppe (battle group) around his I Battalion by adding to it artillery reinforcements and StuG III assault guns, and by instructing the grieving Fritz Witt to push on to Kozani through the Kleidi Pass. In an attempt to fulfil those orders, 7 Company of I Battalion pushed through Vevi village and launched an assault on Point 997 from 7.30 p.m.: the attempt was abandoned due to inadequate artillery support and the gathering darkness. The 2/4th Battalion on the left also reported defeating a heavy attack at this time, and a number of Allied units reported that, in the course of the fighting, two German ‘tanks’, undoubtedly the assault guns, had been disabled on minefields. It would seem from German records that what the Anzacs in fact observed was merely the withdrawal of these vehicles, as Kampfgruppe Witt abandoned its efforts for the day. Vasey duly reported to Mackay at 9.50 p.m. that he had the ‘situation well in hand’.

Nevertheless, the Germans were obviously gathering their strength for a decisive assault on the Allied position. The hard-driving Vasey, clearly appreciating the difficulties facing his men, demanded that they not shirk the issue. He issued an order of the day on the evening of 11 April that said much about his own blunt character: ‘You may be tired,’ he acknowledged, ‘you may be uncomfortable. But you are doing a job important to the rest of our forces. Therefore you will continue to do that job unless otherwise ordered.’

Mitchell, in command of 2/8th Battalion, followed up Vasey’s exhortation and ordered that no member of the unit leave his post from 9.00 p.m. An hour later, the Germans attempted their infiltration trick again, complete with cultured English voices, but on this occasion were met by an alert 14 Platoon that responded with heavy fire. In their unit diaries, the Germans noted the nervousness in the Allied line — any noise during the night was met by a barrage of artillery fire; indeed, the 2/3rd Field Regiment later acknowledged that it spent much of the night firing into a hillside on a false alarm that German tanks had penetrated the pass. Such incidents might seem comical in retrospect, but they also eroded Allied strength: earlier on the 11 April, a squadron of precious cruiser tanks from the 1st Armoured Brigade was despatched from the reserve at Sotire to investigate a report that German tanks were sweeping around the extreme right, along Lake Vegorritis. They found nothing in the barren snow-clad hills, and managed only to disable six of their cruiser tanks when their tracks broke on the rough ground.

By 12 April, the Mackay Force units had nearly accomplished their task, and indeed had orders to begin withdrawing from 5.30 p.m. that evening. Unfortunately, that planned withdrawal was upstaged by the long-heralded German attack. At 6.00 a.m., Dietrich gave his men their final orders: Witt was to punch through the Allied centre and advance on Sotir; a second assault force drawn from the 9th Panzer Division, recently arrived on the scene (Kampfgruppe Appel), would flank the Allied left through Flambouron; and on the Allied right, another impromptu formation from the Leibstandarte, Kampfgruppe Weidenhaupt, would attack Kelli. Meyer’s reconnaissance battalion was ready to exploit any breakthrough, and the Leibstandarte’s assault-gun battery was moved in behind Witt to force the issue.

The decisive action between the Allies and the SS was now at hand. In the bottom of the valley, helping to guard the two-pound guns with the 2/1st Anti-Tank Regiment, was Kevin Price, manning a Bren gun. The first thing that warned Price of the impeding battle was the noise — mechanised warfare brought with it the hum and roar of thousands of petrol engines: ‘We could hear the sound, this tremendous roar as they came down the road, with their tanks and weapons, their motor bikes were out in front, they were testing where we were dug in.’ Shortly after eight in the morning, up on the high ground to the right, Bob Slocombe and the rest of the 14 Platoon, 2/8th Battalion, were getting their first hot meal for days. This welcome breakfast, however, was interrupted by German shelling, and the SS infantry followed in hard behind.

In this foremost Australian position, the 14 Platoon was quickly in trouble. Slocombe remembers his platoon commander, 20-year-old Lieutenant Tommy Oldfield, trying to rally his troops, drawing his service revolver, and moving gamely into the open. A more experienced soldier, Slocombe yelled, ‘For Christ’s sake, Tommy, come back.’ But it was too late, and Oldfield was cut down in this, his first action. As the official historian recorded, Oldfield had enlisted at eighteen, been commissioned as an officer at nineteen, and was now dead at twenty. Even with these heroics, the 14 Platoon was in grave jeopardy, and a number of sections were overrun. Slocombe himself fought his way out to the safety of a reverse slope, where with 17 or 18 others he helped to hold up the Germans until mid-afternoon.

Slocombe’s temper would probably not have been helped had he known that, at 11.50 a.m., headquarters of the 6th Division recorded the action being fought on Point 997 as a ‘slight penetration’ of the defences. The staff of higher command had their minds elsewhere at the time, being deep in conference with Colonel Pappas, a staff officer with the Central Macedonian army, on how the withdrawal of the Dodecanese on the right might be achieved. Without trucks, the Greeks faced the prospect of leaving behind 1200 wounded. The Australians did not always excel at the diplomacy needed to manage relations with their allies: on this occasion, they were clearly frustrated by the scale of the problem presented to them by Pappas; at 1.00 p.m., Mackay finally issued orders to make 30 three-ton lorries available to the Dodecanese. The wounded soldiers whom the trucks could not carry would apparently have to march out, or face capture.

Although headquarters might have been sanguine, the loss of the forward slope of Point 997 had much more profound and unfortunate consequences for the 19 Brigade. In the valley, the 1/Rangers were effectively fighting alongside strangers, having been removed from their familiar role as the infantry element in a tank brigade. The English soldiers, seeing the 14 Platoon in trouble, thought their right had been turned, and began pulling back. In reality, the fighting that morning on Point 997 was only a patrol action, in conformity with Dietrich’s orders that vigorous patrols be sent out prior to the main attack scheduled for 2.00 p.m. However, to exploit any success by these patrols, Dietrich ordered that ‘wherever the enemy shows signs of withdrawing, he is to be followed up at once,’ and the dislodging of the 14 Platoon encouraged the Germans to continue to press the Australians.

Thus, even though the main assault was still being prepared, the German success on Point 997 prompted further local attacks to exploit the opening. Mitchell soon found both B and C companies, on his left, in trouble: he launched a counterattack mid-morning, borrowing a platoon from A Company, on the right, for the purpose, and supported it with covering fire from D Company, in the centre. This had some success, regaining part of the high ground, and the position of the 2/8th was stabilised, at least for the moment.

Down in the valley, however, the withdrawal of the 1/Rangers went on unabated. An officer of the 27 NZ MG Battalion, Captain Grant, the OC 1 Company, attempted to persuade the English infantry to hold their position, without success. Manning his Bren gun, Kevin Price remembers the British infantry streaming past the Australian anti-tank gunners. The withdrawal of the Rangers left these guns, along with the outposts of the New Zealand machine-gunners, without infantry support, and therefore in danger of being overrun. The only option for the gunners was to pull out. Unfortunately, five of the precious two-pounders could not be extricated from the mud in time, and had to be abandoned. By midday, the shaky line of the 2/8th Battalion on the heights on the right formed a large salient, as the Allied centre gave way down the pass; and, on the extreme right, the Dodecanese crumpled in the face of the advance by Kampfgruppe Weidenhaupt.

The Allied line had therefore already lost cohesion when Witt launched his full assault from 2.00 p.m. This was supported in earnest by the StuG III assault guns. Slocombe was astounded by their presence, as his unit had been unable to get their feeble Bren-gun carriers onto the same ground. Another 2/8th veteran, Jim Mooney, found the German armour ‘untouchable’ with the Boys rifle, the standard British anti-tank weapon for infantry units. When the German armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs) came onto an Australian position, there was little that could be done other than move back, covered by the fire of a supporting section.

The collapse of the infantry line exposed the remaining units in the valley who were preparing for the withdrawal. A detachment of the 2/1st Field Company was getting ready the last of the demolitions to break the railway line deep in the pass, south of Kleidi, and Sergeant Scanlon, the leader of this party, found his work interrupted mid-afternoon by the arrival of the SS: ‘We commenced work at about 1500 hours, and had to do a hasty but thorough job as the enemy was advancing both along the road and the railway line with his armoured fighting vehicles.’ Scanlon’s attention to detail was greatly assisted by the nature of the explosives he had to work with, which included two naval depth charges, each with about 250 pounds of TNT packed within. These were used to blow the road: the railway line was disposed of with guncotton charges fixed to the rails. Scanlon readied his getaway car, which was a ‘utility truck with a Bren gun mounted’. He ordered his men to light their charges on the approach of the Germans and then, he describes:

[T]hey had just sighted enemy movement and lit their fuses, when a German patrol, who had worked their way onto a hill commanding this place, opened fire on them with M.G.s. This was at approx 18.30 hrs and was about half an hour after completing the preparation of the demolition. Luckily they got through, the two men on the railway line having to run about 200 yards under fire to gain the vehicle.

With the Vevi position unravelling, Vasey, regrettably, was out of touch with events. As Scanlan got about his work at 3.00 p.m. in the shadow of the panzers, Vasey reported confidently to the 6th Division that he ‘had no doubt that if the position did not deteriorate he would have no difficulty in extricating the Brigade according to plan’.

An officer of the 19 Brigade thought the atmosphere at brigade headquarters that afternoon was ‘almost too cool and calm’, and the implied criticism was warranted. Vasey had wanted to find a headquarters position further forward, but had not found anywhere suitable: as a result, the battle was determind while the Australian commander could only react to events.

At 5.00 p.m., Vasey at last informed 6th Division headquarters that the situation was serious. In response, at 7.45 p.m. the 6th Division sent forward a driver with a message authorising Vasey to bring forward the withdrawal at his discretion; but, in the chaos, the driver could not find him. By then, the position was a good deal worse than serious — the 2/8th was in desperate trouble, having its left flank exposed by the collapse of the 1/Rangers, and outflanked on the right by the withdrawal of the Dodecanese. The strong Allied artillery force at the southern end of the pass was under small-arms and mortar fire by the time of Vasey’s message, forcing the 2/3rd Field Regiment to pull back its 5th Battery, while its 6th Battery covered the movement with fire over open sights — a sure sign that the defence was in trouble, because it meant that the defending gun line was under direct attack. Even Vasey’s own brigade headquarters was under mortar attack. Vasey had little choice but to warn the 2/4th battalion commander, I. N. Dougherty, to get ready to withdraw. ‘The roof is leaking,’ he told Dougherty; as a consequence, the 2/4th had ‘better come over so we can cook up a plot’. Vasey at least took the sensible precaution of ordering his transport to remain where it was: had it come up as arranged, it may well have been mauled by the German armour, and the means to extricate the Allied force may have been lost. He also sent back to the 6th Division a liaison officer to give Mackay an eyewitness report: he arrived at 8.30 p.m., and Mackay thereby learned of the ‘increasing pressure’ on the 19 Brigade and of the discomfiture of the 2/8th Battalion.

Meanwhile, at the 2/8th Battalion headquarters, Mitchell attempted to regain contact with brigade headquarters, the phone line having gone dead. Two signallers sent to repair it were not seen again, so at 4.45 p.m. he despatched his signals officer, Lieutenant L. Sheedy, to the rear to report on the battalion’s plight. Sheedy found what he described as a tank (again, almost certainly a StuG III) already astride the road outside Kleidi, basking in the flames of a wireless truck it had destroyed. The presence of this vehicle cut the most direct and easiest line of withdrawal along the road. Sheedy also observed parties of Germans armed with sub-machine-guns chasing the fleeing 1/Rangers over the neighbouring hills.

By skirting trouble, and gaining shelter behind one of the few light tanks of the 4th Hussars behind the battlefront, Sheedy gained the forward position of the 2/3rd Field Regiment. Even as he gave his report, the artillery headquarters came under German machine-gun fire, and there was nothing in any event that could be done for the 2/8th, as the observation posts needed by the artillery for accurate fire had been swept away in the collapse. Liley, with the Kiwi machine-gunners, had already concluded that, as far as he could see, ‘there was no infantry reserve and no tanks or anything else to restore the position’, so he led his platoon to the rear. For extricating his men and their guns under fire, Liley received the Military Cross.