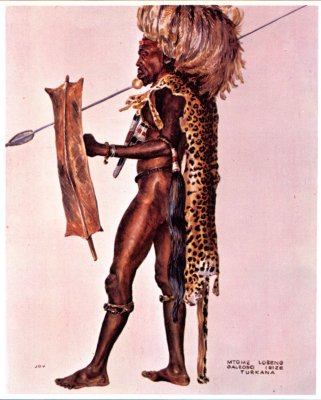

Mtome Loseng of the Turkana

In the far west, beyond Lake Rudolf, lived the most dreaded of all these desert raiders, the Turkana. During the nineteenth century they had expanded south and eastwards at the expense of the Samburu and others, and had even raided as far as Lake Baringo, where they clashed with the Masai. In spite of the extensive territory which they conquered, the Turkana themselves claimed that this was not their main aim: their campaigns were launched to capture cattle to replace their losses in the frequent droughts, but they were so successful at this that their victims eventually moved away to escape the raiding parties, evacuating new grazing lands which the victorious bands then occupied. They continued to clash with an almost equally formidable people, the Karamojong, along the Turkwel River on the border with what was to become Uganda, and sporadically with the Samburu in the east, but elsewhere Turkana expansion had virtually stopped by the 1890s, though this would change early in the twentieth century, when the tribe became a focus of resistance to the British.

By 1900 the Turkana numbered around 30,000 people spread across an area of 24,000 square miles, a population density so low that they were no longer able to muster and feed large armies. The aridity of this territory made it of little interest to potential invaders, so that there was no reason to maintain standing armies for defence. Turkana warfare had become a matter of skirmishing and sudden raids rather than pitched battles. The traditional age-set system gave way to a more locally based organization, and the authority of the elders declined. Life in the desert was so precarious that there was little energy to spare for show and bravado; one twentieth-century informant described the campaigns of his predecessors in strictly practical terms: ‘the Turkana fought to get food’ (Lamphear, 1976). According to a traditional saying, the secret of success in war was ‘not power, but knowledge’. In their painstaking use of reconnaissance, their emphasis on surprise, and the desire to minimize their own casualties while maximizing material gain, the Turkana could perhaps be compared to the Apaches. Captain John Yardley, who fought them in the Northern Frontier District of Kenya during the First World War, describes their tactics as follows:

Like most of their kindred tribes, and in contrast to the Abyssinians, the Turkana had no knowledge of any military formations or movements. They did not need any. Their intimate acquaintance with their own country, where every rock was familiar to them, and every mountain track as easy to find by night as by day, made preconcerted movements superfluous. Even if they had been well drilled, they were far better off when they bolted from one ridge or hollow to another in their own time and by their own route.

The Turkana were very dark-skinned, and did not paint their bodies. Therefore they referred to themselves as ‘black people’, as opposed to the ‘red people’, who included whites as well as the Samburu and Masai, who were naturally paler and painted themselves with red ochre. In the late nineteenth century the Turkana were often believed to be giants, although von Hohnel – the first European to describe them – described them as ‘of middle height only’, though ‘very broad and sinewy, in fact, of quite a herculean build’. Turkana war gear reflected their ruthlessly practical attitude. The spear or akwara was considerably longer than the weapons used elsewhere in the region. An average length was 8 feet, but one ‘giant’ chief seen by Captain Wellby in 1899 carried a spear ‘twice his own length’ – which must have made it more than 12 feet long. The blade was protected when not in use by a leather sheath to keep it sharp. On their right wrists most men wore a circular iron wrist knife or ararait. This peculiar weapon – basically a bracelet with the outer edge kept razor-sharp – could be brought into action almost instantly. In an emergency it could be used without the warrior having to drop his spear or anything else he was carrying, and could inflict serious wounds when grappling at close quarters. Like the spear blades, these knives were usually kept covered by a leather sheath to prevent injury to the wearer. Yardley describes this weapon as ‘the most murderous kind of knife I have ever seen . . . . After throwing their spears, they slipped the scabbard off in a fraction of a second and closed with their enemy. One well-directed gash at the throat would wellnigh decapitate a man, or an upward thrust entirely disembowel him.’ Variants of this type of knife were popular over a wide region of north-east Africa, and in some places they were also worn by women. It was said that Arab slavers would always shoot a woman seen wearing a wrist-knife rather than attempting to capture her, as it was so dangerous to approach her. Other Turkana weapons were wooden clubs and throwing sticks. Their buffalo-hide shields were fairly small and light, befitting the mobile skirmishing tactics which the Turkana preferred, but were solid enough to be used as weapons in their own right if necessary.

In 1895 the British government took over the territories formerly administered by the bankrupt Imperial British East Africa Company. These included what was to become the Northern Frontier District of Kenya, but at that time the frontier had not been surveyed. Since 1891 an agreement had existed with the Italian government, which laid claim to southern Somaliland and to a protectorate over the kingdom of Ethiopia (then commonly known as Abyssinia). However, in 1896 the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik decisively defeated an Italian army at Adowa, securing his country’s independence for the next forty years. It suddenly became necessary for Britain to deal with a power which it had until then disregarded, especially as Ethiopian expeditions soon began to penetrate into the desert south of the escarpment in search of ivory and slaves.

The Fight at Lumian, 1901

The nature of warfare against the Turkana was epitomized by the fate of the Austin expedition. In October 1900 a survey party was dispatched to the Ethiopian border region under the command of Major H H Austin of the Royal Engineers, who had served with Macdonald on his campaign in the far north of Uganda during the war against Kabarega. Austin left Khartoum with three British officers, twenty-three Sudanese soldiers seconded from the Egyptian army, and thirty-two ‘Gehadiah’, former followers of the Mahdi. Both these contingents were armed with Martini-Henry rifles, though in the words of Austin’s second-in-command, Major Bright of the Rifle Brigade, the ex-Mahdists were ‘most indifferent’ shots. This expedition was dogged by misfortune almost from the start. Its members floundered for months in the Nile swamps, and when they emerged near Lake Rudolf they found food and water scarce, and the local tribes, who had mostly welcomed previous visitors, hostile to all outsiders as a result of Ethiopian raids.

Austin made a detour to a Turkana village at Lumian, which was believed to be still friendly, in search of supplies. Having arrived near the village late in the day, he camped in the angle formed by the junction of two small, almost dry river beds. While the camp was still being set up, two soldiers and the cook were ambushed and speared to death by Turkana warriors who quickly vanished into the surrounding scrub. It was now nearly dark, so there was no time either to move the camp or to build a thorn-bush zeriba to protect it. Austin therefore ordered the sentries to keep their rifles loaded, and the rest of the soldiers to sleep at their posts with fixed bayonets. After dark, according to Major Bright’s account, the ‘giant Turkana’ crept close to the camp along the river beds, ‘without the slightest noise’. Then, around midnight, they attacked: ‘Rising as from the ground they rushed with blood-curdling yells on the unprotected camp. They came from three sides, but were met with a steady and rapid rifle fire which appeared to surprise them, for they threw a few spears into camp and then fled. For the remainder of the night we were left unmolested.’

But the Turkana continued to harass the expedition as it marched southwards along the western shore of Lake Rudolf. Large bodies of tribesmen shadowed them just out of rifle range, but ‘when they approached too near they were dispersed with a few well-directed shots’. It soon became clear, however, that smaller groups were keeping them under observation from much closer range, although they were seldom seen. Bright relates how one of the Gehadiah was killed within 100 yards of the camp when he crept out to scavenge some meat from a dead camel. One night a corporal guarding the animals was speared within earshot of his companions by a band of Turkana, who escaped into thick bush before a shot could be fired. After one march, during which no enemy had been sighted all day, a soldier waded across the Turkwel River to bring in a missing donkey, carelessly leaving his rifle on the bank to avoid getting it wet. As soon as he reached the far bank, a group of warriors emerged as if from nowhere and stabbed him to death. By the time the expedition reached safety, it had lost forty-five men from Turkana attacks and exhaustion due to starvation. Only one of the Gehadiah survived the march.